BEACON PRESS

25 Beacon Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892 Beacon Press books

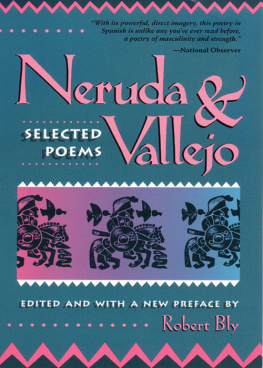

are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. Copyright 1971, 1993 by Robert Bly Copyright 1962, 1967 by the Sixties Press Spanish texts copyright 1924, 1933, 1935, 1936, 1938, 1943, 1945, 1947, 1949, 1950, 1954, 1956, 1958 by Pablo Neruda Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following magazines in which some of these translations have appeared:

The London Magazine, The Nation, The Paris Review, Poetry, The Sixties, The University of Michigan Quarterly, Tri-Quarterly, Dragonfly, The Greenfield Review, Transpacific, Modern Occasions, and Crazy Horse. The translators would like to thank Hardie St. Martin for his generous criticism of these translations in manuscript. The drawings of Pablo Neruda and Csar Vallejo were done specially for the original Sixties Press editions by the Spanish artist Zamorano. cm.

ISBN 0-8070-6489-0 eISBN 978-0-8070-9679-6

1. cm.

ISBN 0-8070-6489-0 eISBN 978-0-8070-9679-6

1.

Neruda, Pablo, 19041973Translations into English.

2. Vallejo, Csar, 18921938Translations into English. I. Bly,

Robert. II. III. III.

Wright, James Arlington, 1927

IV. Neruda, Pablo, 19041973. Poems. English & Spanish.

Selections. 1993. V.

Vallejo, Csar, 18921938. Selections.

English & Spanish. 1993.

PQ8097.N4A6 1993

861dc20 9310400

CONTENTS

READING NERUDA AND VALLEJO IN THE 1990SWalking Around Walking Around

Bruselas Brussels

Toussaint LOuverture Toussaint LOuverture

La United Fruit Co.

The United Fruit Co.

Hymno y regreso Hymn and Return

THE LAMB AND THE PINE CONE(An Interview with Pablo Neruda by Robert Bly)XXIV Al borde de un sepulcro florecido At the border of a flowering grave

READING NERUDA AND VALLEJO IN THE 1990S

Why is it important to read Pablo Neruda now? Because after twelve years of Reagan and Bush we find in him a well of compassion. His mothers death, his fathers death, the rain, broke open his heart. We look in and see compassion for adolescents, for workers, for schoolteachers, for the loneliness of salt.

Competent, chill-hearted, respectable workshop poems flood North American bookstores; but opening Pablo Nerudas poems, readers bite into sea-potatoes, Chilean lions made of sugar, drops of marmalade and blood, a hurricane of gelatin, a tail of harsh horsehair, elephants that fall from the sky. As Neruda says: a tongue of rotten dust is moving forward over the cities movie posters in which the panther is wrestling with thunder. His love of life never falters. His love of women never falters. He loves them, the more unpredictable the better; he remembers Josie Bliss, who was so wild and nearly killed him twice with her knife; but when she went outside at night to piss, the sound was like honey. We know he sits morning after morning at a wobbly table near the sea, writing images blown in from the farthest reaches of his brain, with a discipline fitting for a Mayan weaver woman or a copper craftsman in a North African market.

He wrote the greatest long poem so far created on American ground, that is Canto General. Its 450 poems include careful nature observation, geology, accounts of European invasion, North American meddling, and rage. Neruda worked all his adult life to keep Chile from returning to right-wing control. Finally, in 1973, after his friend Salvador Allende was killed and Allendes government was overthrown, Neruda died. He had been hospitalized with prostate cancer and his condition was stable when the news of Pinochets victory arrived. The Chilean doctors were afraid, not sure how to respond; they suspended treatment, and Neruda died a short while later.

His wife, Mathilde, has written of this night. After his death, Pinochets soldiers and supporters ransacked Nerudas Isla Negra house, broke desks and furniture, burned his letters and unpublished poems. That destruction was disgusting; even the Minneapolis Tribune had an editorial against it. It showed how angry the right wing had become over poetry. It remains a delight to read this wild poet, the spiritual child of Gabriela Mistral, of Whitman, and of the Spanish satirical poet Quevedo. 1938) to be even greater than Neruda. 1938) to be even greater than Neruda.

Vallejo has much American Indian blood, and there is in his work an Indian element. Neruda, who knew Vallejo, remarked: In Vallejo it shows itself as a subtle way of thought, a way of expression that is not direct, but oblique. I dont have it. As a young man Vallejo experienced the injustice dealt to those who protest working conditions in the tungsten mines of Peru; and later he experienced the abuse that the Parisians dealt to South American writers, and the Europeans to Marxists. His political writing belongs with Bertolt Brechts and Nazim Hikmets, and he is a more imaginative poet than either of them: There are blows in life so violentI cant answer! Blows as if from the hatred of God His poetry, without defenses, infinitely human, justly angry, looks more and more solid every year, more irreplaceable, incomparable, heart-breaking, classic. I have a terrible fear of being an animal of white snow, who has kept his father and mother alive with his solitary circulation through the veins His poem The Right Meaning, in which he imagines returning home to Peru to tell his mother about his life in Paris, is the greatest poem Ive ever read on the secrecies and joys between mothers and sons.

Just to be able to translate his poems is a privilege.

Robert BlyUn pilar soportando consuelos

One pillar holding up consolations

254255 Y no me digan nada

And dont bother telling me anything

256257 Y bien? Te sana el metaloide plido?

And so? The pale metalloid heals you?

258259 Tengo un miedo terrible de ser un animal

I have a terrible fear of being an animal

260261Y si despus de tantas palabras

And what if after so many words

262263 La clera que quiebra al hombre en nios

The anger that breaks a man down into boys

264265 From ESPAA, APARTA DE M ESTE CLIZ Masa

Masses

268269 Selected Poems of PABLO NERUDA

REFUSING TO BE THEOCRITUS

Poets like St. John of the Cross and Juan Ramn Jimnez describe the single light shining at the center of all things. Neruda does not describe that light, and perhaps he does not see it. He describes instead the dense planets orbiting around it. As we open a Neruda book, we suddenly see going around us, in circles, like herds of mad buffalo or distracted horses, all sorts of created things; balconies, glacial rocks, lost address books, pipe organs, fingernails, notary publics, pumas, tongues of horses, shoes of dead people. His book,

Residencia En La Tierra (Living On Earththe Spanish title suggests being at home on the earth), contains an astounding variety of earthly things, that swim in a sort of murky water.

The fifty-six poems in Residencia I and II were written over a period of ten yearsroughly from the time Neruda was twenty-one until he was thirty-one, and they are the greatest surrealist poems yet written in a Western language. French surrealist poems appear drab and squeaky beside them. The French poets drove themselves by force into the unconscious because they hated establishment academicism and the rationalistic European culture. But Neruda has a gift, comparable to the fortune-tellers gift for living momentarily in the future, for living briefly in what we might call the unconscious present. Aragon and Breton are poets of reason, who occasionally throw themselves backward into the unconscious, but Neruda, like a deep-sea crab, all claws and shell, is able to breathe in the heavy substances that lie beneath the daylight consciousness. He stays on the bottom for hours, and moves around calmly and without hysteria.