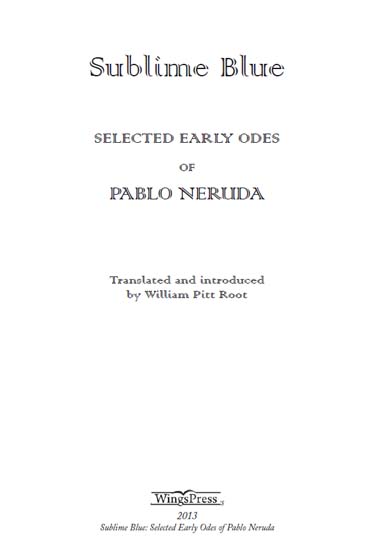

2013 by Wings Press All Spanish texts from Odas elementales 1954 by Pablo Neruda. All English translations 2013 by William Pitt Root. Cover: Mendocino Coastline. Photograph by William Pitt Root. First Edition: Print Edition ISBN: 978-0-916727-87-1 ePub ISBN: 978-1-60940-195-5 Kindle ISBN: 978-1-60940-196-2 Library PDF ISBN: 978-1-60940-197-9 Wings Press 627 E. Guenther San Antonio, Texas 78210 Phone/fax: (210) 271-7805 On-line catalogue and ordering: www.wingspress.com All Wings Press titles are distributed to the trade by Independent Publishers Group www.ipgbook.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Neruda, Pablo, 1904-1973.

2013 by Wings Press All Spanish texts from Odas elementales 1954 by Pablo Neruda. All English translations 2013 by William Pitt Root. Cover: Mendocino Coastline. Photograph by William Pitt Root. First Edition: Print Edition ISBN: 978-0-916727-87-1 ePub ISBN: 978-1-60940-195-5 Kindle ISBN: 978-1-60940-196-2 Library PDF ISBN: 978-1-60940-197-9 Wings Press 627 E. Guenther San Antonio, Texas 78210 Phone/fax: (210) 271-7805 On-line catalogue and ordering: www.wingspress.com All Wings Press titles are distributed to the trade by Independent Publishers Group www.ipgbook.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Neruda, Pablo, 1904-1973.

Sublime Blue: SELECTED EARLY ODES OF PABLO NERUDA/Pablo Neruda; Translated by William Pitt Root. -- First Edition. pages cm This is an English translation of the Spanish texts from Odas elementales 1954 by Pablo Neruda. ISBN 978-0-916727-87-1 (pbk.: alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-60940-195-5 (epub ebook) -- ISBN 978-1-60940-196-2 (kindle ebook) -ISBN 978-1-60940-197-9 (library pdf ebook) I. II. II.

Neruda, Pablo, 1904-1973. Odas elementales. III. Neruda, Pablo, 1904-1973. Odas elementales English. Title. Title.

PQ8097.N4O413 2013 861.62--dc23 2012040300 Except for fair use in reviews and/or scholarly considerations, no portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author or the publisher.

Contents

Dedicated to Pamela, with love, for the brilliance of her spirit reflected in the artesian outpouring of her own odes, and to Bryce Milligan, without whose patience this work may never have seen the dark of printers ink or the light of day.INTRODUCTION

OUR BREAD AND OUR DREAM

W

hen Neruda wrote in his

Memoirs that We must open Americas matrix to bring out her glorious light, he took metaphorically the

el dorado image Corts and company have always taken literally. In doing so, he projected a perspective which, by placing a higher value on light than on the mineral which merely imitates it, resembles the idea of gold prevalent among

las indigenas, the first people native to the American continent. For Neruda, the poets role as explorer was to discover and rediscover the many forms of wealth native to the spirit and to return it all mysteriously gleaming to those closest to the source. Neruda discharged this labor unflaggingly, mining a ceaseless vein of epics, lyrics, and dramatic narratives, stopped only by his death. He died shortly after the bloody CIA-assisted coup on September 11, 1973, which toppled the popular government and ended the high promise of Salvador Allende, his close friend.

Nerudas last words, according to Matilde Urrutia, his wife, were repeated over and over in his final hours: tortured by news of the brutal purge claiming the lives of Allendes friends and sympathizers, the dying poet lapsed in and out of consciousness crying, My people, my people, what are they doing to my people! Nerudas funeral quickly swelled to threatening proportions as his countrymen learned of his death and gathered in the streets to quote verses they knew by heart. This spontaneous convocation constituted what may be construed as the first public show of opposition to Pinochet. About that time, Pinochets forces rerouted a small creek to flood through the poets home, where many of his poems were written and stored. It is unlikely that they appreciated the profound irony of this, given the connection Neruda, throughout his life, had felt with water in all its forms. Among North American poets, the kind of popularity excited by the man born Ricardo Eliecer Neftal Reyes Basoalto and reborn Pablo Neruda, is quite unknown. Only in the figure of Walt Whitman, whom Neruda revered, can we find an equivalent sensibility.

Both men exhibited a spirit whose passionate openheartedness readily engaged at an elemental level the issues and history of their times with the intention of making available to their contemporaries a portrait of themselves, in language close to their own speech, making them participants in a vision they could not otherwise experience so memorably. Whitmans reception, less than a century earlier, little resembled Nerudas acclaim, which began early and lasted throughout his life. Gossiping in the early candlelight of old age, Whitman acknowledged how public criticism on the book and myself as author of it yet shows markd anger and contempt more than anything else. Now an institution, our good grey poet was first reviled as arrogant for proclaiming himself the Poet of the time and as disgraceful (this was the received opinion cited by Emily Dickinson to explain why she had not read her contemporary) for rooting like a pig among a rotten garbage of licentious thoughts. Neruda, however, saw to the center of Whitmans enterprise. I like the postive hero in Walt Whitman who found him without formula and brought him, not without suffering, into the intimacy of our physical life, making him share with us our bread and our dream.

Among the most prolific important poets ever to live, Neruda is, again like Whitman, one of the most widely translated poets of present times. Scores of his poems have appeared in new English translations every year since his death in 1973. The poems in this selection come from his first collection of Odas elementales, published in 1954, when Neruda was about 50. Of this time he has said nothing out of the ordinary happened to me, no adventures that would amuse my readers. Yet it was during this period that he received the Stalin Prize (later renamed the Lenin Peace Prize), and, more importantly, it was then that he and Delia del Carril separated for good and he moved into his new home, La Chascona, with Matilde Urrutia, his beloved, tempestuous, and final wife. When Neruda began writing the odes, in 1952, he already had completed his ambitious Residencia en la tierra (a book he later said breathed the rigidly pessimistic air of the time) and, more recently, his epic Canto general, each a major contribution toward opening Americas matrix.

So, when he turned to the odes it was, in a sense, with a heart unburdened, momentarily relieved of certain charges and free to explore experience at the simplest, most ordinary level. It was as if, reversing the chronology of Blake (whom he translated), having completed a round of songs of experience now he could embark upon these odes of innocence. The famous, widely imitated form he chose for these poemstall, slender poetic stalks, not unlike Queen Anns Lace slowly rocking in a seaside breezebrilliantly suited the air of quick spontaneity these works exude. The phrases fall like thin wrists of water cascading from great heights, exploding at intervals against ledges and obstacles protruding from a sheer cliff-face. Fluent, sinuous, riddled with delightful surprise, the offhand form is also suited to the tone of seemingly casual surmise that can so suddenly pool in a conclusion of great clarity and depth. The poet speaks of his style as a guided spontaneity.

It has also been suggested that the form derives in part from Nerudas plan to serialize these poems for newspapers whose columns, of course, are restrictively narrow. Of his first collection of Odas elementales Neruda declared: I decided to deal with things from their beginnings, starting with the primary state, from birth onward. I wanted to describe many things that had been sung and said over and over again. My intention was to start like the boy chewing on his pencil, setting to work on his composition assignment about the sun, the blackboard, the clock, or the family. Nothing was to be omitted from my field of action; walking or flying, I had to touch on everything, expressing myself as clearly and freshly as possible. Elsewhere he remarked that his tone gathered strength by its own nature as time went along, like all living things.

Next page

2013 by Wings Press All Spanish texts from Odas elementales 1954 by Pablo Neruda. All English translations 2013 by William Pitt Root. Cover: Mendocino Coastline. Photograph by William Pitt Root. First Edition: Print Edition ISBN: 978-0-916727-87-1 ePub ISBN: 978-1-60940-195-5 Kindle ISBN: 978-1-60940-196-2 Library PDF ISBN: 978-1-60940-197-9 Wings Press 627 E. Guenther San Antonio, Texas 78210 Phone/fax: (210) 271-7805 On-line catalogue and ordering: www.wingspress.com All Wings Press titles are distributed to the trade by Independent Publishers Group www.ipgbook.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Neruda, Pablo, 1904-1973.

2013 by Wings Press All Spanish texts from Odas elementales 1954 by Pablo Neruda. All English translations 2013 by William Pitt Root. Cover: Mendocino Coastline. Photograph by William Pitt Root. First Edition: Print Edition ISBN: 978-0-916727-87-1 ePub ISBN: 978-1-60940-195-5 Kindle ISBN: 978-1-60940-196-2 Library PDF ISBN: 978-1-60940-197-9 Wings Press 627 E. Guenther San Antonio, Texas 78210 Phone/fax: (210) 271-7805 On-line catalogue and ordering: www.wingspress.com All Wings Press titles are distributed to the trade by Independent Publishers Group www.ipgbook.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Neruda, Pablo, 1904-1973.