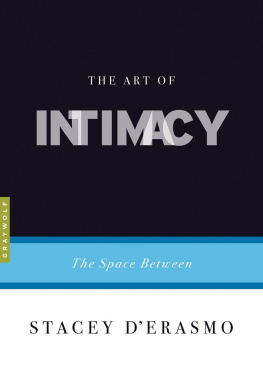

The Art of SERIES

EDITED BY CHARLES BAXTER

The Art of series is a line of books reinvigorating the practice of craft and criticism. Each book is a brief, witty, and useful exploration of fiction, nonfiction, or poetry by a writer impassioned by a singular craft issue. The Art of volumes provide a series of sustained examinations of key, but sometimes neglected, aspects of creative writing by some of contemporary literatures finest practitioners.

The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot by Charles Baxter

The Art of Time in Memoir: Then, Again by Sven Birkerts

The Art of Intimacy: The Space Between by Stacey DErasmo

The Art of Description: World into Word by Mark Doty

The Art of the Poetic Line by James Longenbach

The Art of Attention: A Poets Eye by Donald Revell

The Art of Time in Fiction: As Long As It Takes by Joan Silber

The Art of Syntax: Rhythm of Thought, Rhythm of Song by Ellen Bryant Voigt

The Art of Recklessness: Poetry as Assertive Force and Contradiction by Dean Young

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, Amazon.com, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

All rights reserved.

The kindly way to feel separating is to have a space between. This shows a likeness.

Trying to See

What is the nature of intimacy, of what happens in the space between us? And how do we, as writers, catch or reflect it on the page? One hesitates, perhaps, to be so direct. Like looking directly at the sun, looking directly at the creation of intimacy in fiction seems like a dangerous business. In art as in life, one wishes intimacy to be, or at least to seem, unspoken, unmanipulated, certainly unforced. And, of course, when I talk about intimacy, Im not only talking about romantic relationships between consenting adults. Friendships, the bonds of parents and children, the fleeting communion of strangers at a dinner party or on a train or a plane, crushes, being deeply moved by art or by a historical event, the relationship between reader and writer: in all of these, that space between is vital, electric, and it often drives the story. Only connect, wrote Forster, and we do, for better and for worse; we exhort our characters to do the same.

Moreover, we insist that, in literature, these connections must earn their keep by carrying meaning. They must speak some sort of truth about human existenceethereal, carnal, primal, fleeting, damaging, reparative, beautiful, terrifying, exalted, base, ambiguous, or any combination thereof, these meetings of minds, hearts, and bodies take on a special gravity on the page. We measure their weight against our own experience. As with all other matters in fiction, the composition of these intimacies appears to us to pick out a pattern in the plenitude of everyday life, to find the chord in the cacophony of the street. And then they lived happily ever after. This is not the part of the story that engages us. We want to know what they said, how they looked, what was exchanged between them, what it all meant, and how it went down. Who was lost, who was found, and why? Every time one character approaches another, makes that perilous crossing into the space between, the reader knows that what happens next will be critical, it will produce a change. When we read a well-wrought piece of fiction, we long for that change, for the good or the ill, to occur.

Recently, I was waiting for a visitor to arrive. His plane was delayed. To pass the time and because I wanted to see it, I went to the Matthew Marks Gallery to see the Nan Goldin photo exhibit Scopophilia. In this project, Goldin was invited by the Louvre to pair photos of hers with imagery from the painting and sculpture in the museum. Goldin was given access to the Louvre in the off-hours so that she could take photos of the artwork that interested her. She paired four hundred images of hers with images from pieces in the Louvre; in addition to these framed pairings, she created a twenty-five-minute-long slide installation. The slide installation combines images of her work and of work in the Louvre with classical music composed by Alain Mah and a musing voiceover composed of Goldins thoughts on the work and readings from Ovids Metamorphoses, St. Teresa, and others.

Goldins work, which first came to prominence with her 1986 series of photos The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, is intensely personal. Throughout her career, she has focused on taking photographs of friends and lovers of both genders at their most naked, often literally. Here is her ex-lover Siobhan getting out of the shower, arms upraised, the look on her face both seductive and challenging. Here is a young man with extraordinary ice-blue eyes, naked, smoking, the look on his face both seductive and challenging. Here are families with children, women alone, drag queens and transsexuals, naked pregnant women, couples sleeping, children playing, people making love, men and women looking directly into the camera with frank desire or aggravation or hostility or affection, or all of these at once, and often with a clear pleasure in being looked at. As the art critic Vince Aletti has written, she has been the prime iconographer of the downtown scene, a pansexual bohemia on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Goldin, as a vulnerable member of that bohemia, has been her own subject many timesshe has photographed herself with her eyes blackened by a lover, naked in bed staring at a (presumably unringing) phone, in moments of joy, of pain, of confusion, of connection and disconnection.

Her great subject has been intimacy in all forms, among all genders, and in all emotional modes. In the Louvreone of the less intimate spaces on the planetGoldin found a treasure house of intimate moments, gestures, gazes, facial expressions, and bodily positions. She focused in on details from larger, grander works to discover the crook of a lovers arm around another, a face carved from marble turned at the most tender of angles, skeins of hair flowing over an exposed breast, mutual gazes, and many physical curves and hollows. We notice anew the curve of Cleopatras breasts in Cleopatra with the Asp; the lyricism of a naked back in Cupid with His Wings on Fire; the downward tilt of Galateas chin in Pygmalion and Galatea. These details, paired with her modern subjects in ordinary rooms and landscapes, might suggest an aggrandizement of the present momentheres how my hot girlfriend looks just like Winged Victory getting out of the showerbut actually the pairings work the other way around, by reminding us that these august paintings and sculptures are impressions, painstakingly rendered, of living human beings, now gone. These works of art are also vivid fossils of intimacy. To Goldin, the human connection, and the yearning for that connection, are everywhere, even in the most exalted and reified spaces. Moreover, she never gets tired of looking at them. Scopophilia, after all, means the love of looking, or, as Goldin puts it, the intense desireand the fulfillment of that desireexperienced through looking. One of the desires prominently on display in this exhibition was Goldins unabashed desire to look, and look again, and look still more. Walking into the Louvre at night for the first time, Goldin says in the voiceover, she was surprised by her own very intense reaction to the visual abundance that surrounded her.