The Thirteenth Turn

Copyright 2014 by Jack Shuler.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com .

Book Design by Pauline Brown

Typeset in 12.5 pt Adobe Garamond Pro by the Perseus Books Group

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shuler, Jack.

The thirteenth turn : a history of the noose / Jack Shuler.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61039-136-8 (hardback)ISBN 978-1-61039-137-5 (electronic) 1. HangingUnited StatesHistory. 2. LynchingUnited StatesHistory. 3. ViolenceUnited StatesHistory. I. Title. HV8579.S58 2014

364.1'34dc23

2014007475

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

I would like to first thank the amazing individuals who let me interview them and shared their hearts and minds and time. I am grateful.

Writing this book made me aware of the many limits to my intellectual abilities. If not for the help of countless librarians and fellow researchers, it wouldnt have happened. One person who was a constant touchstone for research was the ever-exceptional Joshua Finnell. I was ably assisted by four gifted scholarsHolly Burdorff, Olivia Nienaber, Cecilia Salomone, and Elisabeth Halseand a treasure trove of Denison librarians past and present, including Lareese Hall, Michael DeNotto, Pam Magalaner, and, especially, Susan Rice, who tracked down many obscure sources for me.

Many wonderful people read parts or all of the manuscript. I appreciate their efforts on my behalf. The flaws that may appear in this book are my fault alone. Thank you, Gene Shaw, Jon-Christian Suggs, Mark Noonan, Bill Munn, Walter Hoover, Mitchell Snay, Paul Thompson, Katharine Jager, Benjamin Gessner, Toni The Enforcer Lisska, Dennis Read, Keir Bickerstaffe, Jim Davis, James Weaver, and Mike Croley.

Linda Krumholz and Fred Porcheddu were my first and last readers. You two are gems.

Many thank yous to all my talented colleagues in the Denison English Department and its fearless organizer and captain, Anneliese Davis. Thank yall for giving me a home and a sounding board.

Generous funding from the Denison University Research Foundation helped support my research. A special thank you also to Denison faculty who offered assistance along the way, including Laurel Kennedy, Toni King, Sylvia Brown, Ann Townsend, Erin Henshaw, Isis Nusair, Andrew McCall, David Baker, Stephen Kershner, Harold Von Broekhoven, David Busan, Sandy Runzo, and Jess Clawson.

The amazing folks at Sandra Dijkstra Literary Agency, including Sandy and my friend and champion, Elise Capron, helped make this book a book. Thank you, Elise, for believing in this project.

Thank you to all of the inspired folks at PublicAffairs including Benjamin Adams, Brandon Proia, Clara Platter, Josephine Mariea, and Melissa Raymond.

Many thank yous to the curators, librarians, and volunteers in all the archives, museums, and historical/genealogical societies I visited, phoned, or e-mailed. Yall are the front line, the guardians of history and story in this country, and your work is key to our future.

Countless people looked up random facts/tidbits, helped me make contact with people to interview, and offered advice along the way: Craig Keeney, Chris Johnson, Rabbi Robert Kaplan, Peter Hawes, Anna Connor, Becky Michaels Anderson, Heidi Beirich, Lloyd Bourgeois, Terry Bradford, Fred Counts, Bill Munn, Sheri Sharlow, Crys Armbrust, Susan Thoms, Lee Morgan, Betsy Blake, James Burgess, David S. Reynolds, Jane Rissler, Bill Barker, Doug Perks, Chris Evans, Elizabeth Baer, Rick Lybeck, Nic Butler, Leo Riegert, Joan Hunstiger, Mo Stemen, Niels Lynerup, Markil Gregerson, Ole Nielson, Anne E. Bentley, Kalki Winter, the Brothers Snyder, Lin Fredericksen, Blair Tarr, Laura L. Phillippi, Bruce Elleman, Patricia Schaefer, Chuck Haddix, Edward J. Akins, Theodore Miles, Rico Ainslie, Alan Bean, Trina Seitz, Marva Felchlin, Katy Klettlinger, Richard Graves, Neal Coil, David Turk, Todd A. Cox, Hayes Oakley, and Rick Williams. Im sure Im leaving someone(s) out, and I do apologize.

To the craftsmen and women of the International Guild of Knot Tyers, thank you for letting me join and participate in your annual guild meeting. Thanks especially to Glenn Dickey, Colin Byfleet, Lindsey Philpott, and Owen K. Nuttall.

To Ceciel, Amelie, and Frankiethank you for tolerating my absences and for anchoring me. I love you all.

Lastly I would like to acknowledge the response and activism of Denison University students during the fall semester of 2007, my first semester on campus. Their reaction to seeing the noose and their ways of understanding this powerful symbol inspired the writing of this book. My colleagues across the campus and, in particular, my friend and fellow CUNY Graduate Center alum Nida Bikmen deepened my knowledge and encouraged me to write this book. That experience reinforced something my parents taught me long agoviolence must be met with examination and dialogue, not with more violence .

An oak tree stands in the center of the campus commons at Jena High School in Jena, Louisiana. Its an imposing oak with stretching limbs ringed by sidewalks and the kind of well-trodden grass one finds at many American high schoolssandy spots here, a discarded potato chip bag there. A tree whose limbs offer shade at lunchtime and underneath which, rumor had it, only white students could sit. But it was August, and a few black students wondered whether they could sit there too; theyd also heard the rumors but didnt believe them. They asked the principal, who said they could sit wherever they pleased.

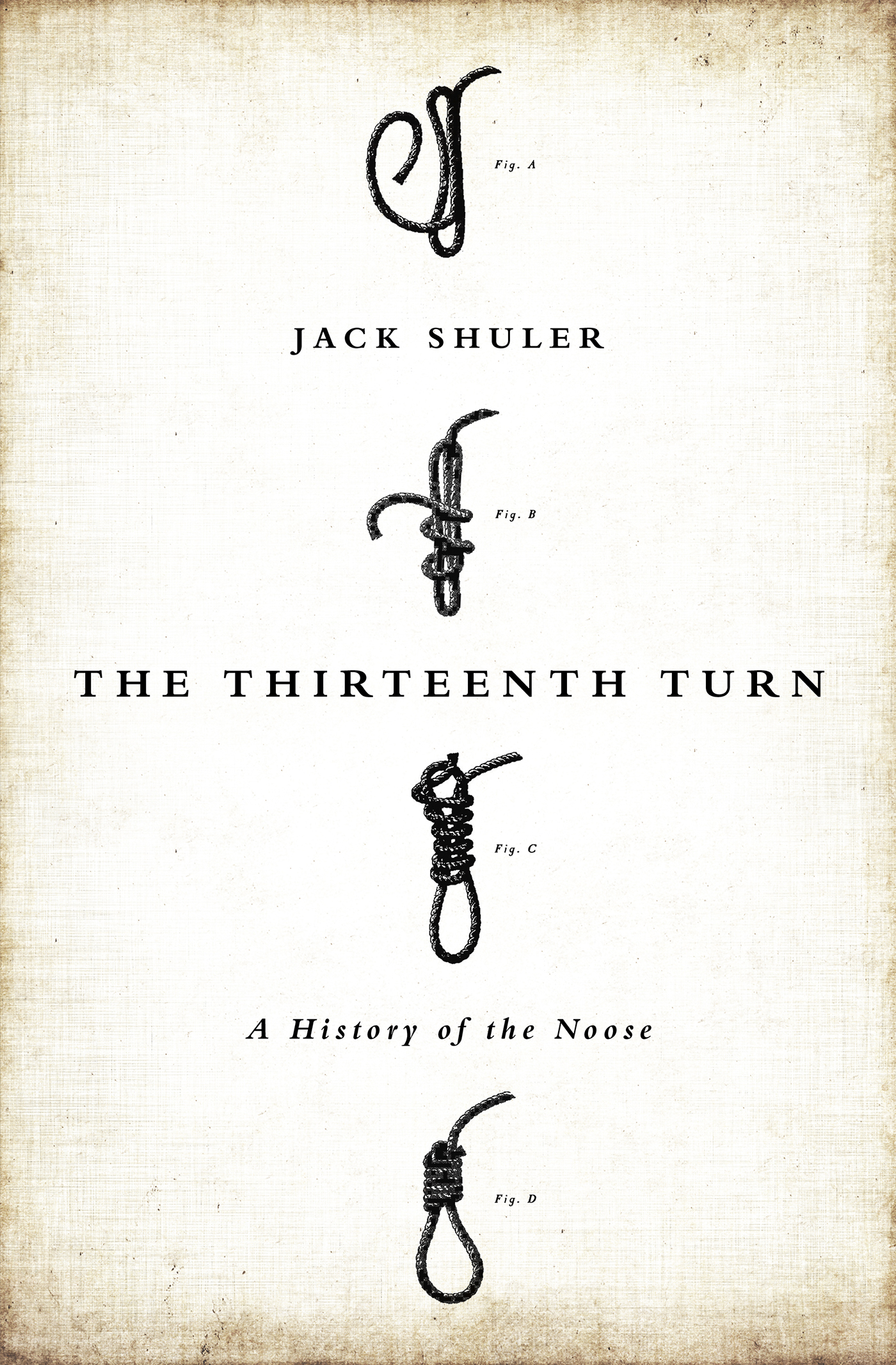

The next day two nooses, or, more specifically, hangmans knots, fashioned from nylon rope, were found hanging from that oak tree. It was already Louisiana sticky-hot in the early morning, and the nooses hung like dead weights in the thick airimmovable reminders of a past thats not even past, to borrow from William Faulkner. A school administrator cut them down, but the message had already been delivered.

A day later a group of black students held a sit-in beneath that tree, and the school launched an investigation to identify the culprits. It didnt take long to find themthree white students did it, they said, as a joke. Those students spent nine days away from the school and two weeks at in-school suspension, and then were required to undergo psychological evaluations. The local school superintendent claimed that many persons of authority interviewed the three students and that the result of those interviews showed that the students were not motivated by hate and there was no indication from any of the students that they had any inclination to do any violence.

Jenas noose incident was followed by several violent encounters between black students and white students on and off campus. When a group of black students apparently beat up a white student, the accused were brought up on charges of attempted murder and conspiracy to commit murder. News of those charges spread nationally, and Jenas noose incident became part of a national conversation. On September 20, 2007, this little Louisiana town played host to one of the largest civil rights demonstrations in recent years. Jena was in the news and in the public consciousness, and soon nooses started showing up everywhereat workplaces, in front of private homes, or dangling from trees at schools across the country. These noose incidentsa clunky but widely used term used to describe a range of eventsinvolve one or more persons using a noose in order to intimidate another. The noose referred to here is usually a particular kind of noose, the hangmans knot or hangmans noose, a knot consisting of somewhere between six and thirteen loops or wrapping turns. These nooses are often fashioned from rope or sometimes drawn on a piece of paper, but recently nooses also have been sent as text messaged photos, in faxes, or in e-mails. In many cases a noose incident is considered a hate crime.