This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1999 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

ABSTRACT

ACROSS THE BORDER: THE SUCCESSES AND FAILURES OF OPERATION ROCKCRUSHER by MAJ Donald V. Phillips, USA.

This study examines the planning, execution, and results of US military involvement in the 1970 Cambodian incursions. Named Operation Rockcrusher, the attacks targeted North Vietnamese sanctuaries in officially neutral Cambodia. Strategic guidance for the operation reflected the Nixon administration's desire to proceed with troop reductions and quickly Vietnamize the war in Southeast Asia. Efforts to set conditions for a U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, including a covert bombing campaign of Cambodia, failed. These factors, along with a deteriorating political situation within Cambodia, led to approval of the assaults.

The thesis describes the operational and tactical objectives that were derived from the strategic situation. Then, by discussing key portions of the campaign, the study examines how well the US Army accomplished these objectives. Reviewed within the context of selected battlefield operating systems, the operation reveals a decided mixed bag of success and failure.

The study highlights lessons that may be appropriate to today's lower intensity conflict environment and force structures. It also promotes the need to synchronize goals and objectives throughout the levels of war. It concludes that attritional warfare, a dubious legacy from Vietnam, remains a danger to the Army today.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper would have been impossible without the support and assistance of many people. First, I would like to thank my committee staff, Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) Geoff Babb, Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) Bill Connor, and Dr. Gary Bjorge. Their guidance and mentorship not only improved this paper, but also my development as a professional officer. I deeply appreciate Dr. Philip Brookes and his staff for their untiring support of the MMAS program. Thanks to the research staff of the US Army Center for Military History and the Combined Arms Research Library for their assistance in locating primary sources. Appreciation goes to Lieutenant Colonel George Steuber, Bert Chole, Dr. Arif Dirlik, Dr. Bill Chafe, and Dan Richner. Most importantly, I thank my wife, Evelyn, my children, James, Vicky, and Richard, and the Lord, for supporting with me through this project.

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

There has never been a protracted war from which a country has benefited. General Sun Wu Tzu, The Art of War

At 9:00 P.M., 30 April 1970, President Richard M. Nixon went on television to address the American public on the situation in Southeast Asia: Ten days ago, in my report to the nation on Vietnam, I announced a decision to withdraw an additional 150,000 Americans from Vietnam over the next year. I said then that I was making that decision despite our concern over increased enemy activity in Laos, in Cambodia, and in South Vietnam.

With the aid of a large map containing red zones of major Communist influence, President Nixon spoke of past American policy toward the Kingdom of Cambodia. He also discussed a growing North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) presence along the Cambodian-South Vietnamese border. Given the reduction of American involvement mentioned earlier, many in the audience gasped at the President's next statements:

In cooperation with the armed forces of South Vietnam, attacks are being launched this week to clean out major enemy sanctuaries on the Cambodian-Vietnam border.Tonight, American and South Vietnamese units will attack the headquarters for the entire Communist military operation in South Vietnam.

This key control center has been occupied by the North for five years in blatant violation of Cambodia's neutrality. This is not an invasion of Cambodia. The areas in which these attacks will be launched are completely occupied and controlled by North Vietnamese forces. Our purpose is not to occupy the areas. Once enemy forces are driven out of these sanctuaries and once their military supplies are destroyed, we will withdraw.

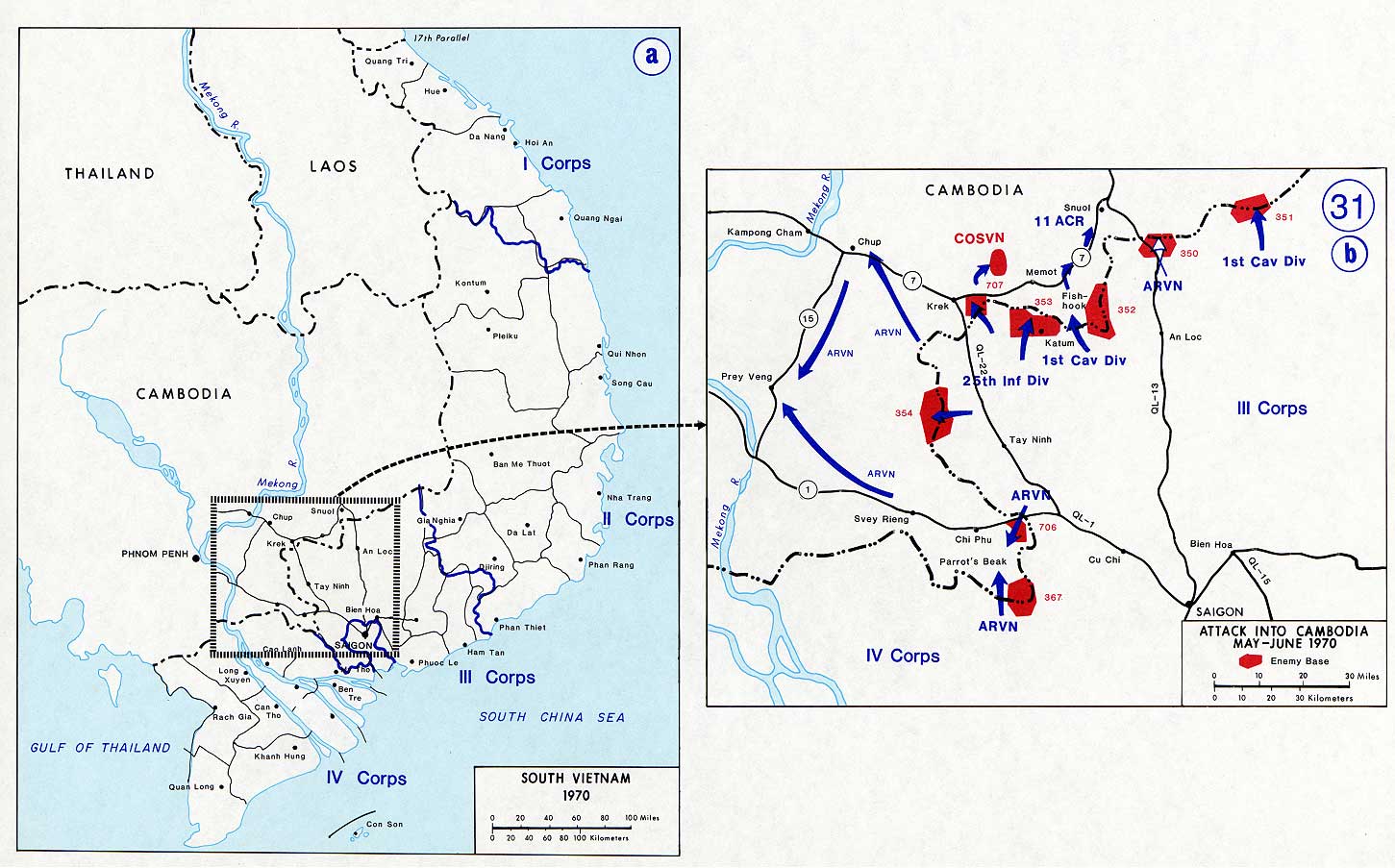

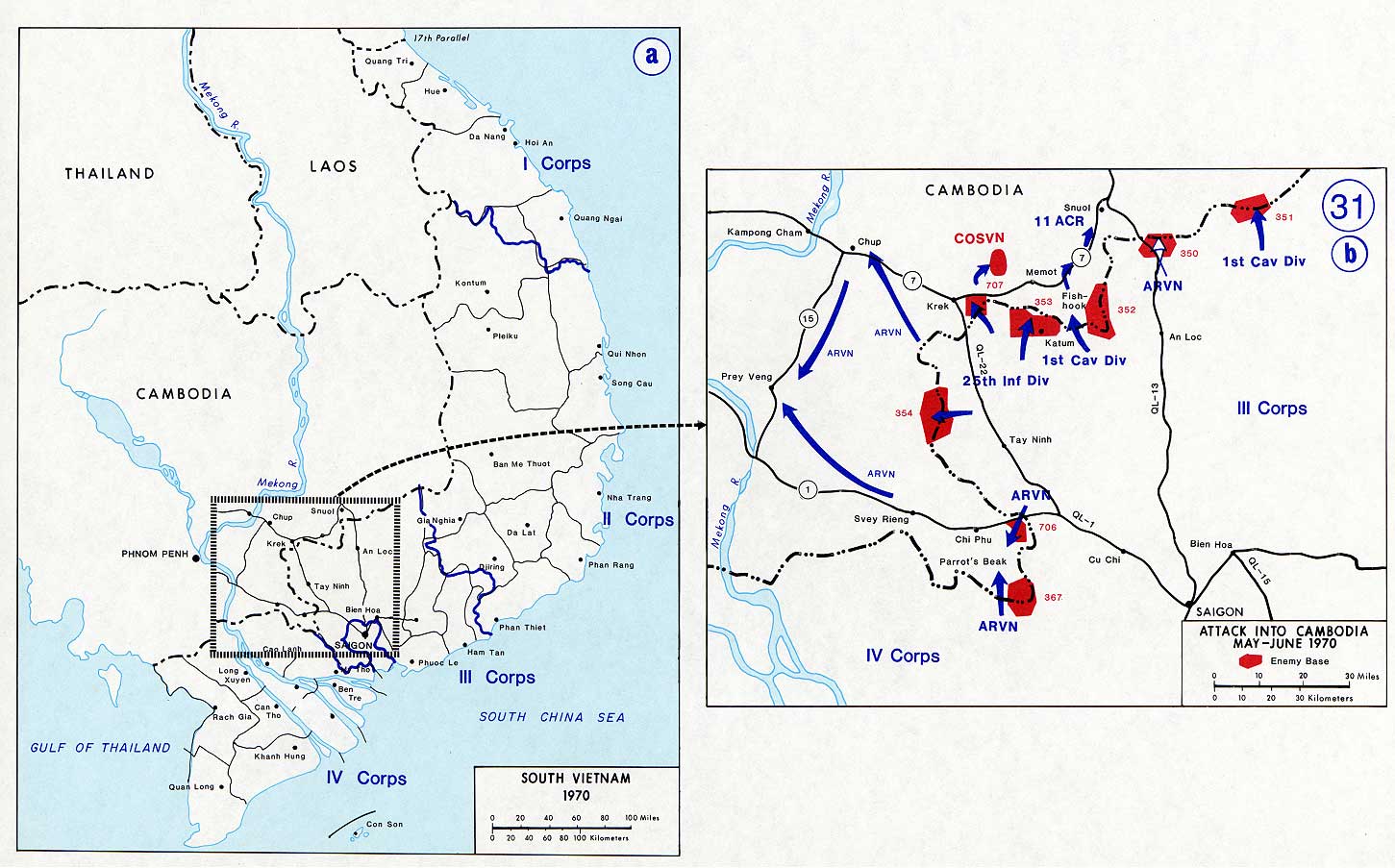

While President Nixon spoke, over 25,000 US and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops assaulted Communist bases across the Fishhook, a forty-mile swath of the Cambodian border. Farther to the south, ARVN forces launched a similar operation in the Parrot's Beak region of the border. The Vietnamese named these operations Toan Thang (Total Victory) 42 in the Parrot's Beak and Toan Thang 43 in the Fishhook. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), code-named the assaults Rockcrusher. These were the first operational cross-border attacks by conventional ground forces of the war (figure 1).

Major elements of the 25th Infantry Division, 1st Cavalry Division, and the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR) sought to trap elements of the 5th Viet Cong and 7th North Vietnamese Army Divisions in their previously safe sanctuaries. Intelligence reports described large training and refitting bases and supply caches throughout the border. Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), the supreme communist field headquarters, also operated somewhere in the area.

From the outset, President Nixon imposed major restrictions on the invasion force. All Americans involved in the operation would be withdrawn by 30 June 1970. US penetration would be limited to thirty kilometers (rounded up to twenty-two miles by the Pentagon) from the border. After the initial assaults, operations would focus on force protection and destruction of captured communist infrastructure. With these missions and limitations, Allied forces invaded Cambodia. With this action, the myth of Cambodian neutrality ended and the Vietnam War was openly recognized as the Second Indochina War.

The battle for Snoul, a town located at a key road junction near the border, exemplifies the pace of the operation. After a sixty-kilometer drive through the eastern edge of the Fishhook, Colonel Donn Starry's 11th ACR halted the third morning of the assault to reconnoiter and plan for the capture of the town. Although armored cavalry had served in Vietnam long before the incursions, commanders often relegated its use to route-bound escort duties and reaction force applications. This situation would provide an opportunity for the regiment's armored vehicles to be used in a more traditional offensive fashion.

Next page