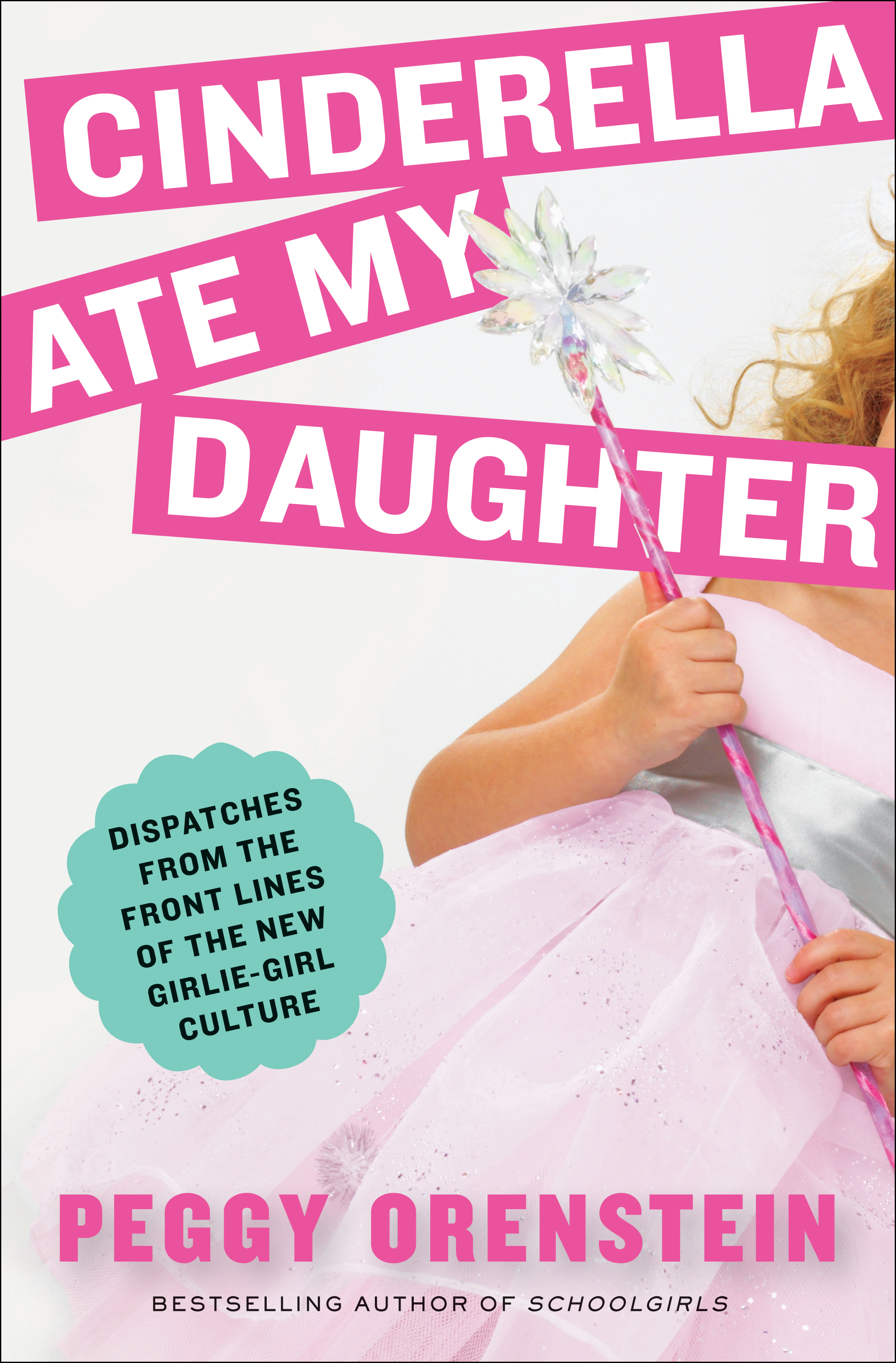

CINDERELLA ATE MY DAUGHTER

DISPATCHES FROM THE FRONT LINES OF THE NEW GIRLIE-GIRL CULTURE

PEGGY ORENSTEIN

for daisy

Contents

H ere is my dirty little secret: as a journalist, I have spent nearly two decades writing about girls, thinking about girls, talking about how girls should be raised. Yet, when I finally got pregnant myself, I was terrified at the thought of having a daughter. While my friends, especially those whod already had sons, braced themselves against disappointment should the delivery room doc announce, Its a boy, I felt like the perpetual backseat driver who freezes when handed the wheel. I was supposed to be an expert on girls behavior. I had spouted off about it everywhere from The New York Times to the Los Angeles Times , from the Today show to FOX TV. I had been on NPR repeatedly . And that was the problem: What if, after all that, I was not up to the challenge myself ? What if I couldnt raise the ideal daughter? With a boy, I figured, I would be off the hook.

And truly, I thought having a son was a done deal. A few years before my daughter was born, I had read about some British guy whod discovered that two-thirds of couples in which the husband was five or more years older than the wife had a boy as their first child. Bingo. My husband, Steven, is nearly a decade older than I am. So clearly I was covered.

Then I saw the incontrovertible proof on the sonogram (or what they said was incontrovertible proof; to me, it looked indistinguishable from, say, a nose) and I suddenly realized I had wanted a girldesperately, passionatelyall along. I had just been afraid to admit it. But I still fretted over how I would raise her, what kind of role model I would be, whether I would take my own smugly written advice on the complexities surrounding girls beauty, body image, education, achievement. Would I embrace frilly dresses or ban Barbies? Push soccer cleats or tutus? Shopping for her layette, I grumbled over the relentless color coding of babies. Who cared whether the crib sheets were pink or glen plaid? During those months, I must have started a million sentences with My daughter will never...

And then I became a mother.

Daisy was, of course, the most beautiful baby ever (if you dont believe me, ask my husband). I was committed to raising her without a sense of limits: I wanted her to believe neither that some behavior or toy or profession was not for her sex nor that it was mandatory for her sex. I wanted her to be able to pick and choose the pieces of her identity freelythat was supposed to be the prerogative, the privilege, of her generation. For a while, it looked as if I were succeeding. On her first day of preschool, at age two, she wore her favorite outfither engineers (a pair of pin-striped overalls)and proudly toted her Thomas the Tank Engine lunchbox. I complained to anyone who would listen about the shortsightedness of the Learning Curve company, which pictured only boys on its Thomas packaging and had made Lady, its shiny mauve girl engine, smaller than the rest. (The other females among Sodors rolling stock were passenger cars passenger cars named Annie, Clarabel, Henrietta, and, yes, Daisy. The nerve!) Really, though, my bitching was a form of bragging. My daughter had transcended typecasting.

Oh, how the mighty fall. All it took was one boy who, while whizzing past her on the playground, yelled, Girls dont like trains! and Thomas was shoved to the bottom of the toy chest. Within a month, Daisy threw a tantrum when I tried to wrestle her into pants. As if by osmosis she had learned the names and gown colors of every Disney PrincessI didnt even know what a Disney Princess was. She gazed longingly into the tulle-draped windows of the local toy stores and for her third birthday begged for a real princess dress with matching plastic high heels. Meanwhile, one of her classmates, the one with Two Mommies, showed up to school every single day dressed in a Cinderella gown. With a bridal veil.

What was going on here? My fellow mothers, women who once swore they would never be dependent on a man, smiled indulgently at daughters who warbled So This Is Love or insisted on being addressed as Snow White. The supermarket checkout clerk invariably greeted Daisy with Hi, Princess. The waitress at our local breakfast joint, a hipster with a pierced tongue and a skull tattooed on her neck, called Daisys funny-face pancakes her princess meal; the nice lady at Longs Drugs offered us a free balloon, then said, I bet I know your favorite color! and handed Daisy a pink one rather than letting her choose for herself. Then, shortly after Daisys third birthday, our high-priced pediatric dentistthe one whose practice was tricked out with comic books, DVDs, and arcade gamespointed to the exam chair and asked, Would you like to sit in my special princess throne so I can sparkle your teeth?

Oh, for Gods sake, I snapped. Do you have a princess drill, too?

She looked at me as if I were the wicked stepmother.

But honestly: since when did every little girl become a princess? It wasnt like this when I was a kid, and I was born back when feminism was still a mere twinkle in our mothers eyes. We did not dress head to toe in pink. We did not have our own miniature high heels. Whats more, I live in Berkeley, California: if princesses had infiltrated our little retro-hippie hamlet, imagine what was going on in places where women actually shaved their legs? As my little girl made her daily beeline for the dress-up corner of her preschool classroom, I fretted over what playing Little Mermaid, a character who actually gives up her voice to get a man, was teaching her.

On the other hand, I thought, maybe I should see princess mania as a sign of progress, an indication that girls could celebrate their predilection for pink without compromising strength or ambition; that at long last they could have it all: be feminist and feminine, pretty and powerful; earn independence and male approval. Then again, maybe I should just lighten up and not read so much into itto mangle Freud, maybe sometimes a princess is just a princess.

I ended up publishing my musings as an article called Whats Wrong with Cinderella? which ran on Christmas Eve in The New York Times Magazine . I was entirely unprepared for the response. The piece immediately shot to the top of the sites Most E-mailed list, where it hovered for days, along with an article about the latest conflict in the Middle East. Hundreds of readers wrote inor e-mailed me directlyto express relief, gratitude, and, nearly as often, outright contempt: I have been waiting for a story like yours. I pity Peggy Orensteins daughter. As a mother of three-year-old twin boys, I wonder what the land of princesses is doing to my sons. I would hate to have a mother like Orenstein. I honestly dont know how I survived all those hyped-up images of women that were all around me as a girl. The genes are so powerful.

Apparently, I had tapped into something larger than a few dime-store tiaras. Princesses are just a phase, after all. Its not as though girls are still swanning about in their Sleeping Beauty gowns when they leave for college (at least most are not). But they did mark my daughters first foray into the mainstream culture, the first time the influences on her extended beyond the family. And what was the first thing that culture told her about being a girl? Not that she was competent, strong, creative, or smart but that every little girl wantsor should wantto be the Fairest of Them All.

It was confusing: images of girls successes aboundedthey were flooding the playing field, excelling in school, outnumbering boys in college. At the same time, the push to make their appearance the epicenter of their identities did not seem to have abated one whit. If anything, it had intensified, extending younger (and, as the unnaturally smooth brows of midlife women attest, stretching far later). I had read stacks of books devoted to girls adolescence, but where was I to turn to understand the new culture of little girls, from toddler to tween, to help decipher the potential impactif anyof the images and ideas they were absorbing about who they should be, what they should buy, what made them girls ? Did playing Cinderella shield them from early sexualization or prime them for it? Was walking around town dressed as Jasmine harmless fun, or did it instill an unhealthy fixation on appearance? Was there a direct line from Prince Charming to Twilight s Edward Cullen to distorted expectations of intimate relationships?

Next page