Table of Contents

To Emi, my sweet girl.

Introduction

When I was pregnant with my daughter, I was thrilled to be expecting a girl. Other people, though, were concerned. Is your husband okay with that? they asked. Dont worry, they reassured me, you can try again. Some even gave me tight-lipped tsks of warning. Girls are tough, they said. Others were happy for me, visions of flouncing pink dresses and promises of mother-daughter bonding evidently overtaking any urge they might have had to dispense admonitions.

My own feelings lay somewhere between the two extremes. My husband was fine with having a girl, I wasnt worried about needing to try again for a boy, I outright disbelieved the rumor that girls were harder to raise, and pink held no particular allure for me.

Mother-daughter bonding, thoughthat was a potential stumbling block. Having a girl felt natural to me, but Id be lying if I said I didnt worry just the slightest that our relationship might be unavoidably, inescapably fraughtless the stuff of happy shopping trips and more the stuff of door-slamming dramafests. Still, I felt confident that even if some of the mother-daughter territory might be treacherous, at least it would be familiar.

When I was pregnant with my son, I was decidedly more ambivalent. After the babys male status was revealed at the ultrasound, it took me a few weeks to wrap my head around the fact that I had a boy baby inside me; that I would soon be a mother not to two sisters, but to a girl and a boy. This time the strangers were uniformly ecstatic.

You must be so happy! As though I wouldnt be if I were carrying a girl. Or, Your husband must be proud! As if hed be disappointed to have another daughter. Countless people told me how easy boys are; how loving, how sweet, how special, how different from girlsoften, and appallingly, right in front of my three-year-old daughter.

This prompted me to further investigate the its a boy / its a girl divide. I spoke and exchanged emails with other mothers and writers about mothering boys and girls, and I asked the following questions: Are there real differences between mothering a son and mothering a daughter? Are the ideas we have about boys and girls based on genuine differences between them, or do our ideas about their differences inform their behavior? Do boys truly love their mothers differently? Are girls really difficult? Are boys really easy? Do these stereotypes about boy and girl babies change in toddlerhood? Adolescence?

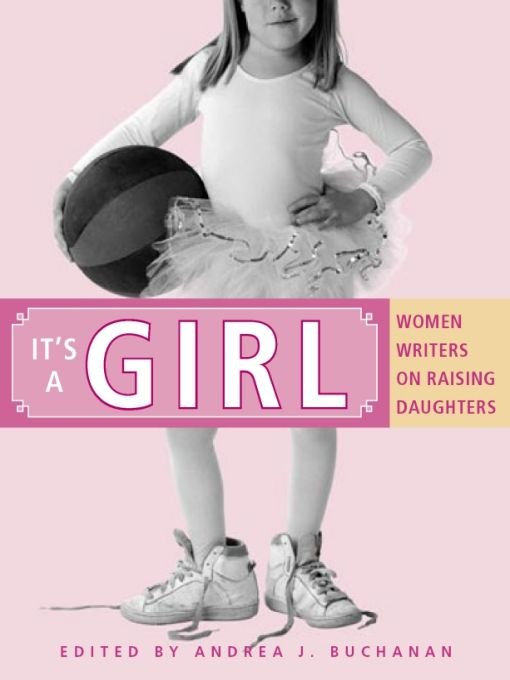

The conversation this sparked inspired me to embark on two essay collections about mothering boys and mothering girlsnot instructional tomes or guidebooks, but literary explorations of what it means to mother sons and daughters, and of the differences between girls and boys. This book and its companion piece, Its a Boy: Women Writers on Raising Sons, published in 2005, are the result.

Like Its a Boy, the essays in Its a Girl are grouped into four sections, with each sections title coming from one of the essays in that group. The first section is Shining, Shimmering, Splendid, referencing an essay that takes it title from lyrics to the Disney princess song A Whole New World. In this section, writers confront the new world of being a mother to a daughter instead of a daughter to a mother, working out the various messages of feminism, princess power, and what makes a girl a girl. The second section, On Beauty and a Daughter, features frank writing on body image, eating disorders, plastic surgery, and the culturaland maternalexpectations of feminine beauty. The third section, Garden City, examines both the complicated joy of mother-daughter bonding and the somewhat darker notion of girl-mothering as a way to heal wounds from the past. The final section, Passing it On, is about letting go, and about the ongoing dance of cleaving and separation between mothers and daughters.

In Shining, Shimmering, Splendid, eight writers discuss their ambivalence about what one essayist calls contemporary American girldom. The world of girlsin the pinkest, sparkliest, most princessy sense of the wordis largely foreign for these mothers, most of them self-identified feminists, products of the changing cultural landscape of the70s and 80s. Many of these writers chafe at the restrictions they feel are placed on them due to gender and wonder how they can raise a girl when they are so conflicted themselves. In Her Perfect Woman, Carolyn Alessio suspects that her true calling might not be as a mother, but as a 1950s husbandthe kind who stays late at the office and returns home after drinks with friends just in time to catch a glimpse of the baby before bedtime. Kim Fischer, a mother of triplets, discovers the power of princesses when her three girls succumb to the siren song of Disney characters in Shining, Shimmering, Splendid. In Ladylike, Gabrielle Smith-Dluha is dismayed that her five-year-old girl might be destined to forever be a rap-loving tomboy, thanks to her two older brothers and her mothers lack of feminine wiles. Rebecca Steinitz (Tough Girls) admits to unabashed brainwashing about the power and potential of girls in the course of raising her two hard-core minifeminists, and novelist Jacquelyn Mitchard traces her evolution from boy-mother to girl-mother as she embraces her new daughter, and her own feminine side, in Confessions of a Tomboy Mom. Yvonne Latty writes about living in a Girl House, with an all-girl family that includes two moms, and how the girly daughter she never expected has given her a second shot at girlhood herself. Author Miriam Peskowitz (Cheerleader) confronts the fact that at six years old, her daughter seems to be embracing the role of girl as cheerleadera role that women of her mothers generation worked so hard to subvert. Finally, Martha Brockenbrough, in Its a Girl, explores her own ambivalence about being female and reveals what becoming the mother of two girls has shown her about self-acceptance and gender.

In the second section, On Beauty and a Daughter, six writers investigate the power of beauty, and the complicated, ultimately subjective nature of being a beautiful girl. Jenny Blocks On Being Barbie, a piece about the authors experience with multiple plastic surgeries, questions whether a mother who takes inordinate pride in her appearance can effectively impart to her daughter the lesson that beauty comes from within. In The Food Rules, Canadian parenting author Ann Douglas discovers her teenage daughters eating disorder and wonders what role her own focus on weight loss might play in it. Novelist Gwendolen Gross (Feeling Is First: On Beauty and a Daughter) is more surprised by her daughters empathy than her striking beauty, and ponders whether that combination of beauty and compassion will serve her girl or make her more vulnerable. In Breasts: A Collage, Rachel Hall writes of her own memories of budding womanhood, contrasting that with her mothers breast cancer and her daughters own journey toward puberty. Novelist Joyce Maynard is frank about the inescapable maternal pride and prejudice of having a beautiful baby in The Worlds Most Beautiful BabyTake Two. And Catherine Newman comes right out with the F-wordfatin her essay Baby Fat, about the surprising reaction of strangers to her baby girls plumpness, and her own reaction to the postpartum plenitude of her own body.