ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is one of the results of the Art, Agency and Living Presence project that was hosted by the Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society (LUCAS) and its predecessors at the Humanities Faculty of Leiden University from 2006 to 2011. It was funded very generously by the Dutch Foundation for Scientific Research (NWO). I want to thank NWO, and the anonymous reviewers who judged the grant appplication, for their suppport. Without it, this project, and the line of research that was developed in it, could never have taken place. I also want to thank Groningen University, and particularly Auke van der Woud, for their support in earlier stages of the project, which were equally vital to its coming into being. At Leiden University Ton van Haaften, at the time Dean of the Humanities Faculty, Reindert Falkenburg and Kitty Zijlmans persuaded me to join the Department of Art History, and I have never regretted that decision. Indeed, the Art and Agency project found an ideal intellectual atmosphere in the typically Leiden atmosphere of intense collaboration between art historians, classicists, historians, literary scholars, archaeologists and anthropologists.

The other members of the project, Stijn Bussels, Lex Hermans, Joris van Gastel, Elsje van Kessel and Minou Schraven, were ideal sparring partners, but above all they became very dear friends. I thank them all for their sharp thinking, generous contributions and great sense of humor. Our guests at the expert meetings we organized at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies in Wassenaar were very generous with their time and expertise: Jeremy Tanner, Robert Layton, Maarten Delbeke, Jrgen Pieters, Karl Enenkel, Frank Fehrenbach, Christine Goettler, Malcolm Baker, Arthur DiFuria, Jeanette Kohl, Arno Witte and Joanna Woodall.

Several conferences that we organized in the course of the project also contributed to this book: the sessions we hosted at the Renaissance Society Meeting in Venice in 2010; the conference Waking the Dead. The Poetics of Presence in the Wake of the French Revolution, held at the Acadmie de France at the Villa Medicis in Rome in 2011, organized together with Sigrid de Jong, Stijn Bussels and Bram Van Oostveldt; and the concluding conference of the Art and Agency project held in Leiden in 2011. I wish to thank Marc Bayard, Annick Lemoine and Angela Stahl at the Villa for their generosity and exquisite hospitality.

While writing this book I benefited from many conversations with friends and colleagues: Pamela Edwardes, as always a wonderful editor, critic and listener, who pointed me in the way of Alfred Gell; Maarten Delbeke, who drew my attention to Sforza Pallavicino and thus unwittingly provided the clue towards a major step in the argument of this book; Pascal Griener, who very kindly did not point out he had already, twenty years ago, covered in much greater depth many of the ideas on 18th-century viewing practices that I discussed with him; Odile Nouvel suggested towards an entirely new way of thinking about fetishism. Frank Ankersmit, Jas Elsner, Patricia Falguires, Jason Gaiger, Daniela Gallo, Edward Grasman, Sigrid de Jong, Anna Knaap, Alina Payne, Bettina Reitz, Frits Scholten, Philippe Snchal, Louk Tilanus, Bram van Oostveldt, Chris Wood, and Hendrik Ziegler all gave generously of their time and learning.

Whereas Alfred Gell was the tutelary deity of the first part of the Art and Agency project, Aby Warburg took over that role for the second part. The Warburg-Haus in Hamburg invited Elsje van Kessel, Joris van Gastel and me to speak at one of their graduate student conferences, and there a wonderful collobaration began, which resulted in the series Kunst und Wirkmacht/Art and Agency , in which the books resulting from our project are published in a collaboration with Akademie Verlag (now De Gruyter) and Leiden University Press. I want to thank Uwe Fleckner, Director of the Warburg-Haus, Heiko Hartmann at Akademie Verlag, and Yvonne Twisk at Leiden University Press for their enthousiasm and great efficiency in putting this idea into reality. I also want to thank the present staff of these publishers, Anniek Meinders in Leiden, and Martin Steinbrck and Verena Bestle in Berlin and Munich, for the great care with which they have published this book. Frederik Knegtel and Marit Eisses offered vital assistance in the final stages of editing and finding images.

But as often, the greatest debt is the most difficult to put into words. I want to thank Hende Bauer for telling me take the plunge into the deep waters of the life of art. Without one short conversation in the Prado, the intellectual adventure of which this book is one of the results would never have taken off.

EPILOGUE

FROM THE ANIMATED IMAGE TO THE EXCESSIVE OBJECT

THE APPEARANCE OF THE SOUL

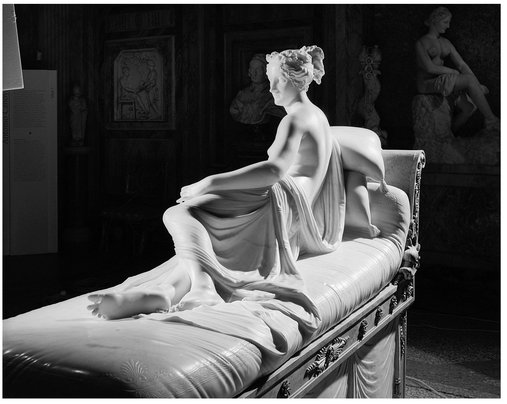

This book ends where it began, in the Villa Borghese. In 1804 Prince Camillo Borghese asked the sculptor Canova to make a statue of his wife Pauline, Napoleons favourite sister. The result, finished in 1808, was a lifesize portrait of Pauline reclining naked on a bed, represented as Venere Vincitrice , Venus victorious: she holds the apple that Paris gave her when asked to choose the most beautiful goddess ( fig. 77 ). It was shown to the public for the first time in 1809, in the Palazzo Chiablese in Turin, where the Prince at this time held court, as governor of Piemonte appointed by his brother-in-law. It is probably the first statue of this size representing a living woman, and a very public figure as well, naked, and as a goddess.

From the moment the Venere Vincitrice was shown it became scandalous. The beauty of the model, the pose, the nudity, and the fact that Pauline Borghese had posed naked for Canova were already sufficient to attract a crowd. But the extreme virtuosity of Canovas treatment of the body of the goddess and in particular his ability to suggest the softness and lustre of living skin also made the statue a celebrity. Both Canovas biographer Missirini and his friend Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremre de Quincy report on the crowds that came to gaze at the statue at night, illuminated by torches, to appreciate, as Canova himself also claimed, much better than by daylight le gradazione della carnagione, the rendering of the living and breathing body.

These nocturnal viewings of Pauline Borghese as Venus are part of the fashion for looking at statues by torch light that had originated in late 18th-century Rome, where it had been propagated at the Villa Albani, and reached its culmination in the nocturnal visits by Napoleon and his court to the newly arrived Laocoon in the Muse Napolon ( fig. 78 ). The French diarist Joseph Joubert observed how, under such viewing conditions, in the flickering light statues seem to move towards the viewer from the dark. The play of light on the marble suggests living skin, and ces formes idales et molles dont les corps anims semblent comme environns [apparaissent] chaque trait et quun philosophe appelait les apparences de lme.

77 Antonio Canova (17571822), Pauline Borghese as Victorious Venus , 1808, marble, L. 2.00 m., Rome, Villa Borghese. Photo Alinari

Another feature added to the excessive nature of this statue: its genesis. As mentioned, Pauline Borghese had posed naked to the sculptor. When asked how she felt about this, she famously replied, well, the room was heated.