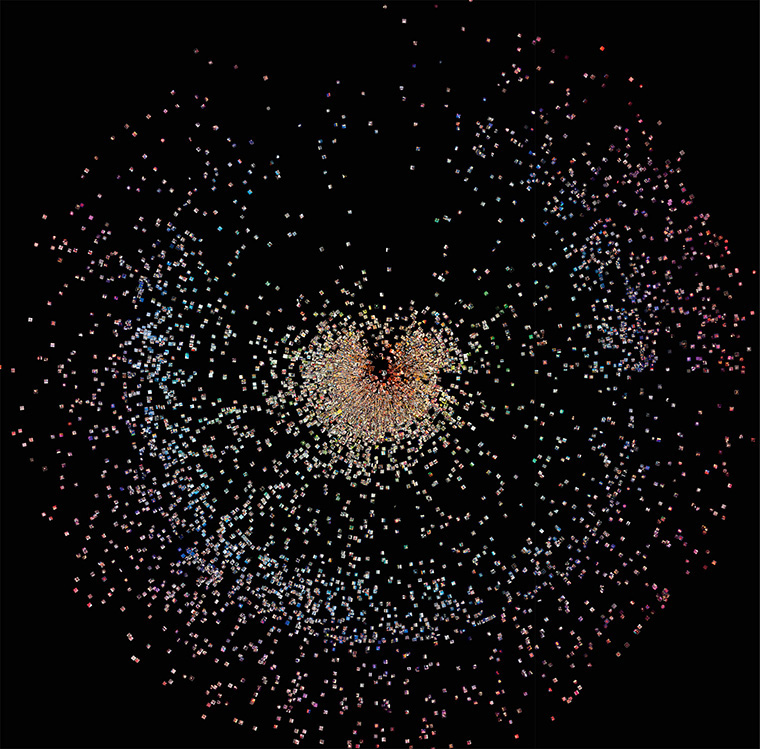

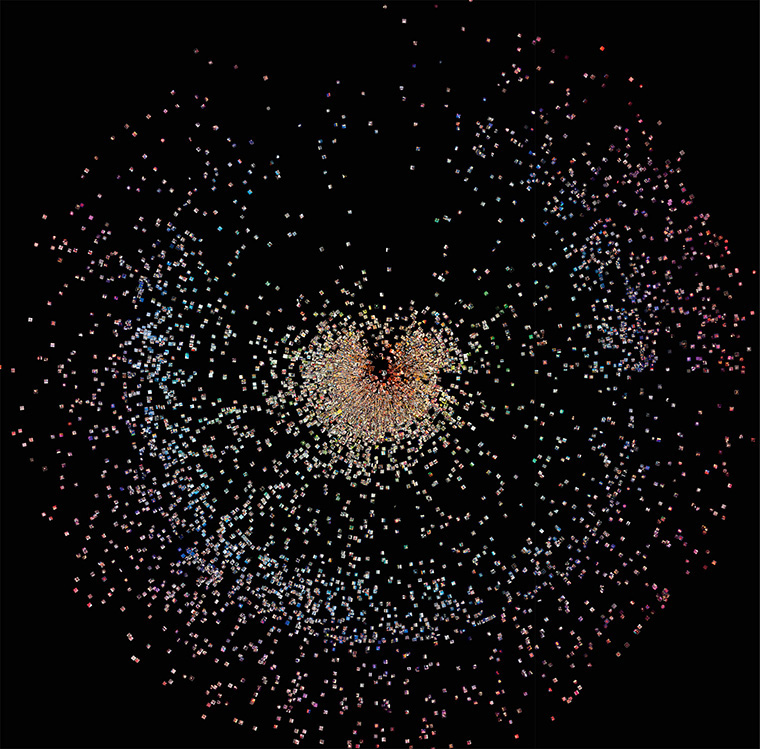

. Nadav Hochman, Lev Manovich and Jay Chow, Phototrails.net, 2012. Radial image plot visualization of 11,758 photos shared on Instagram in Tel Aviv, Israel, 2526 April 2012.

About the author

Christiane Paul is the Adjunct Curator of New Media Arts at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and Professor in the School of Media Studies at The New School, New York. She has curated numerous exhibitions at the Whitney Museum and internationally, written extensively on new media arts, and lectured around the world on art and technology.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Video Art

Art of the Digital Age

100 Works of Art That Will Define Our Age

Art Since 1900

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

For my parents

Acknowledgments

My special thanks go to all the artists, curators, and critics who, for two decades, have generously shared their knowledge and ideas with me. This book would not have been possible without them.

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 as

Digital Art: Third Edition

ISBN 978-0-500-20423-8

by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

and in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

Digital Art 2003, 2008 and 2015 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

This electronic version first published in 2015 by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

This electronic version first published in 2015 in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110.

To find out about all our publications, please visit

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-500-77274-4

ISBN for USA only 978-0-500-77275-1 (e-book)

On the cover: Aram Bartholl, Dead Drops, 2010.

Courtesy DAM Gallery, Berlin & XPO Gallery, Paris

Contents

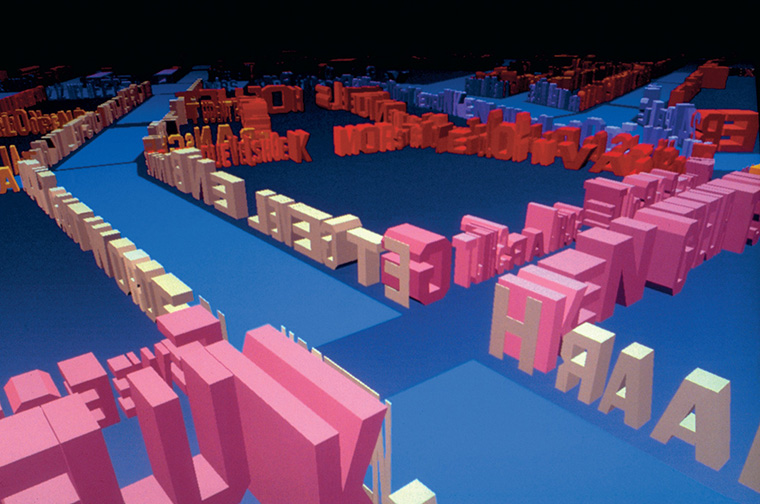

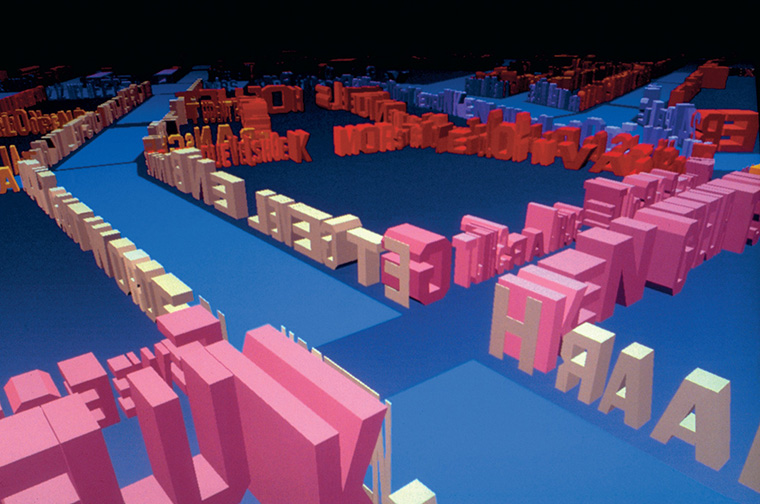

2. Jeffrey Shaw, The Legible City (Amsterdam), 1990

Introduction

From the 1990s to the early twenty-first century, the digital medium has undergone technological developments of unprecedented speed, moving from the digital revolution into the social media era. Even though the foundations of many digital technologies had been laid up to sixty years earlier, these technologies became seemingly ubiquitous during the last decade of the twentieth century: hardware and software became more refined and affordable, and the advent of the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s added a layer of global connectivity. Artists have always been among the first to reflect on the culture and technology of their time, and decades before the digital revolution had been officially proclaimed, they were experimenting with the digital medium. At first, the fruits of their labours were mostly exhibited at conferences, festivals, and symposia devoted to technology or electronic media, and were considered peripheral, at best, to the mainstream art world. But by the end of the century, digital art had become an established term, and museums and galleries around the world had started to collect and organize major exhibitions of digital work.

The terminology for technological art forms has always been extremely fluid and what is now known as digital art has undergone several name changes since it first emerged: once referred to as computer art, then multimedia art and cyberarts (from the 1960s90s), digital art now is often used interchangeably with new media art, which at the end of the twentieth century was used mostly for film and video, as well as sound art and other hybrid forms. The qualifier of choice here new points to the fleeting nature of the terminology. But the claim of novelty also begs the question, what exactly is new about the digital medium? Some of the concepts explored in digital art date back almost a century, and many others have been previously addressed in various traditional arts. What is in fact new is that digital technology has now reached such a stage of development that it offers entirely new possibilities for the creation and experience of art. Some of these possibilities will be outlined here.

The term digital art has itself become an umbrella for such a broad range of artistic works and practices that it does not describe one unified set of aesthetics. This book will provide a survey of the multiple forms of digital art, the basic characteristics of their aesthetic language, and their technological and art-historical evolution. One of the basic but crucial distinctions made here is that between art that uses digital technologies as a tool for the creation of more traditional art objects such as a photograph, print, or sculpture and digital-born, computable art that is created, stored, and distributed via digital technologies and employs their features as its very own medium. The latter is commonly understood as new media art. These two broad categories of digital art can be distinctly different in their manifestations and aesthetics and are meant as a preliminary diagram of a territory that is by its nature extremely hybrid. Definitions and categories can be dangerous in setting up predefined limits for approaching and understanding an art form, particularly when it is still constantly evolving, as is the case with digital art. Many artists, curators, and theorists have already pronounced an age of post-media and post-Internet that finds its artistic expression in works both deeply informed and shaped by digital technologies, yet crossing boundaries between media in their final form. While this book tries to be as inclusive as possible when it comes to the various manifestations of digital art, it still presents only a small selection of the broad range of digital work that has been created. Many of the forms and themes of digital art outlined in the following pages could easily be subjects of entire books of their own.

A short history of technology and art

For obvious reasons, the history of digital art has been shaped as much by the history of science and technology as by art-historical influences. The technological history of digital art is inextricably linked to the military-industrial complex and to research centres, as well as to consumer culture and its associated technologies (a fact that plays a prominent role in many of the artworks discussed in this book). Computers were essentially born in an academic and research environment, and still today research centres play a major role in the production of some forms of digital art.

In 1945, Atlantic Monthly published the article As We May Think by army scientist Vannevar Bush, an essay that had a profound influence on the history of computing. The article described a device called the Memex, a desk with translucent screens that would allow users to browse documents and create their own trail through a body of documentation. Bush envisioned that the Memexs contents books, periodicals, images could be purchased on microfilm, ready for insertion, and that there would also be possibilities for direct data entry by the user. The Memex was never built, but it can be seen as a conceptual ancestor to electronic linking of materials and, ultimately, to the Internet as a huge, globally accessible, linked database. It was essentially an analogue device, but in 1946, the University of Pennsylvania presented the worlds first digital computer, known as ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), which took up the space of a whole room; and 1951 saw the patenting of the first commercially available digital computer, UNIVAC, which was capable of processing numerical as well as textual data. The 1940s also marked the beginnings of the science of cybernetics (from the Greek term

Next page