Roman Architecture

A Visual Guide

Diana E. E. Kleiner

Yale University Press

New Haven & London

Copyright 2014 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

For William L. MacDonald, teacher and mentor, who famously said, "in the study of architecture there can be no substitute for leaning against one's buildings," and for my son Alex who has leaned on so many of mine with me.

Table of Contents

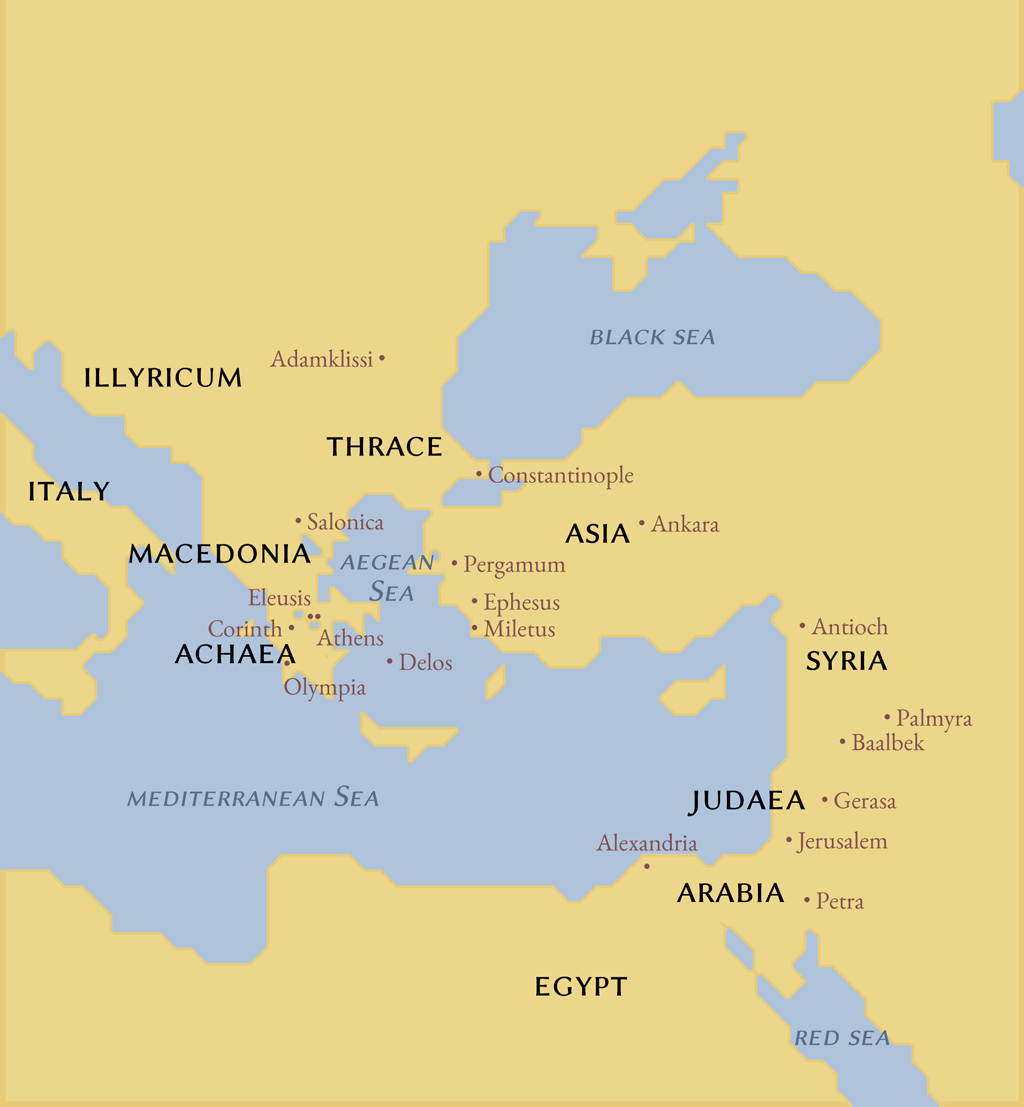

Maps of the Roman Empire

Chapter 1

Roman Architecture

A Great Story to Tell

In Roman Architecture: A Visual Guide, I try to tell a story as compelling as the Romans' own, using digital images and text to explore how they envisioned their world, what they built, and the enduring impact of those edifices. This new e-book includes a listing of monuments not only by chapter but also by location, with links to Google Maps.

The Romans possessed a passionate wanderlust, a deep desire for travel resulting primarily from their mission to create an empire, accumulate foreign lands, and build cities. In the process, they also marshaled men, money, and masonry to reshape the politics, society, and culture of the ancient world.

This visual narrative begins with the birth of Rome as an Iron Age village and how it became a world-class city and a vast empire encircling the Mediterranean Sea. At its apex, Rome was the ancient world's greatest superpower, centered in Italy but stretching all the way from the British Isles to Egypt. The Romans embraced a new technologyconcrete construction (opus caementicum)and used it to create an innovative architecture of vaults and domes that revolutionized the ancient world and exerted a lasting impact on the architecture and architects of post-classical times.

The basic building block of Roman imperialism was the Roman city. A collection of Roman cities concretized the Roman concept of an empire without end that, by the age of Rome's first emperor, Augustus, encompassed three continents. A Roman city was essentially conceived as a miniature version of Rome, an entity with the same basic components as the capital. But Rome was a strange archetype, because unlike most of its colonies it developed over many centuries in an ad hoc manner, attested by the narrow and crooked streets that still weave their idiosyncratic way through the modern city. Today that eccentricity seems quintessentially Roman, especially in the way urban elements are layered on top of one another, accumulating new associations, while retaining some of their former meaning. Indeed, Rome is a palimpsest, resembling its own wax-coated tablets that were repeatedly inscribed, erased, and reused. Designs that were ubiquitous in ancient Rome were reinforced later, seamlessly merging past with present.

The Scalinata della Trinit dei Monti (Spanish Steps), for example (). Linking the Trinit dei Monti church and piazza to the Piazza di Spagna at the base of the Scalinata, the steps seem to slide down the hillside in undulating waves. Like a Roman forum, the Piazza di Spagna serves as a place for social and commercial interaction, and is defined by many of the same visual markers: religious building and obelisk from the ancient Roman Orti Sallustiani gardens at the top and, at the base, the seven-teenth century Barcaccia fountain in the shape of a boat. Later famous Rome landmarks, Babington's Tea Room and the Keats-Shelley Memorial House, flank the staircase to left and right.

1.1 Scalinata della Trinit dei Monti (Spanish Steps), Rome, ca. 1725

Despite Rome's impromptu urban design, Roman surveyors who built cities from scratch were as methodical in their urban planning as Rome was in executing a war. Ostia, Rome's first colony and chief port, was built as a military camp, or castrum (). Nothing was left to chance, the two main streets (cardo and decumanus) intersected at the center, the main civic buildings took their assigned places, and the residential and commercial enterprises were arranged around them.

Military might made Romans aware that an attack could happen at any time, and they wisely walled their cities in the fourth century B.C. The city's fabled Seven Hills were protected with a defensive stone circuit in 378 B.C. () replaced the Servian Walls in A.D. 275.

Each early Roman colony on Italian soil had at least one communal meeting and market place. This forum was always located at the intersection of the cardo and decumanus in a castrum plan. The Forum at Pompeii ()

Each forum had at least one temple. While some are in ruins, others are spectacularly preserved. Two in exceptionally good condition, the Maison Carre at Nmes and the Pantheon in Rome, are at opposite ends of the spectrum in intent and design. By the age of Augustus, city building was fully under way in the Roman provinces, and the Maison Carre was part of that surge (), round in plan and surmounted by a dome, is the best example of the sculptural manipulation of an interior envelope of space by a gifted architect with a new objective.

Each Roman city had its market. The concrete shopping extravaganza that Trajan built in Rome is a spectacular accomplishment. Indeed, the Markets of Trajan () prefigure the modern shopping mall, with 150 shops terraced over a hill, providing a wide variety of retail experiences.

Since most Roman houses had no running water, public bath buildings were important in Roman cities. They were also integral to Roman social life, and the cities and their architects paid considerable attention to their construction. Baths had to supply the requisite bathing facilities but also be the kind of places that people wanted to go. The evolution of Roman bath architecture is fascinating, as is how adventurous its designers were even in early Roman Pompeii, with one room in particular, the frigidarium () were exercises in personal aggrandizement by their imperial sponsors but also provided bathers with a wealth of intellectual as well as bathing opportunities, an example of how prescient the Romans were about wellness.

The Roman city's entertainment district consisted of theaters, music halls, and amphitheaters. Examples survive from most major cities. Many follow a relatively strict adherence to an accepted mode, even the Colosseum, which remains today the very icon of the city of Rome. Relatively conservative in its own day, the Colosseum boasted the first use of the groin or ribbed vault on the second story (), making it clear that even architects working from the standard playbook were innovators.