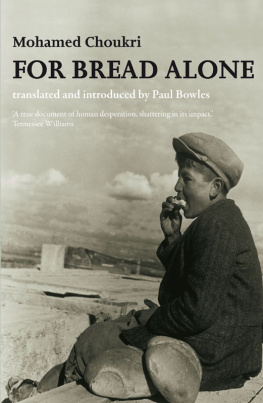

Surrounded by the other boys of the neighbourhood, I stand crying. My uncle is dead. Some of them are crying, too. I know that this is not the same kind of crying as when I hurt myself or when a plaything is snatched away. Later on I began to see that many people cried. That was at the time of the great exodus from the Rif. There had been no rain, and as a result there was nothing to eat.

One afternoon I could not stop crying. I was hungry. I had sucked my fingers so much that the idea of doing it again made me sick to my stomach. My mother kept telling me: Be quiet. Tomorrow were leaving for Tangier. Theres all the bread you want there. You wont be crying for bread any more, once we get to Tangier.

My little brother Abdelqader was too sick to cry as I did. Look at your little brother, she told me. See how he is. Why cant you be like him?

I stare at his pallid face and his sunken eyes and stop crying. But after a few moments I forget to be inspired by his silence, and begin once more to cry.

When my father came in I was sobbing, and repeating the word bread over and over. Bread. Bread. Bread. Bread. Then he began to slap and kick me, crying: Shut up! Shut up! Shut up! If youre hungry, eat your mothers heart. I felt myself lifted into the air, and he went on kicking me until his leg was tired.

We were making our way towards Tangier on foot. All along the road there were dead donkeys and cows and horses. The dogs and crows were pulling them apart. The entrails were soaked in blood and pus, and worms crawled out of them. At night when we were tired we set up our tent. Then we listened to the jackals baying.

When someone died along the road, his family buried the body there in the place where he had died. After we had set out Abdelqader began to cough, and the cough grew worse as we went along. Fearful for his sake and my own, I said to my mother:

Will Abdelqader die too?

No, of course not. Who said he was going to die?

My uncle died.

Your brothers not going to die. Hes sick, thats all.

I did not see as much bread in Tangier as my mother had promised me I should. There was hunger even in Eden, but at least it was not a hunger that killed. One day when the hunger had grown too strong, I went out to An Ketiout to look in the garbage dump for bones and ends of dry bread. I found another boy there before me. He was barefoot and his clothes were in shreds. His scalp was covered with ringworm, his arms and legs scarred with sores.

The garbage in the middle of town is a lot better than it is here, he said. Nazarene garbage is the best.

After that I wandered further afield in search of food, sometimes alone, sometimes with another boy who was looking for the same thing. One day I found a dead hen. I seized it and hugged it close, for fear someone would snatch it away.

Mother in the city, Abdelqader propped against the cushions. His huge eyes, half shut, watched the entrance door. He sees the hen, and his eyes open wide. He smiles, his thin face flushes, he moves, coughs. I find the knife. I turn towards the east, as my mother always does when she is about to pray.

I said: Bismillah. Allahou akbar. And I kill it as I have seen grown-ups do it.

I drew the knife back and forth across its throat until its head fell off. I was waiting to see the blood come out.

I massage the bird a little. Maybe it will come out now.

A few drops of blackish blood appeared in its open gullet. In the Rif I had watched them kill a sheep. They put a bowl under its throat to catch the blood. When the bowl was full they gave it to my mother, who was sick in bed. They held her down and made her drink it. Her face and clothing were smeared with it. Why doesnt the blood come out of the hen the way it did with the sheep?

I began to pull off the feathers.

I hear her voice. What are you doing? Where did you steal that?

I found it. It was sick. But I killed it before it died.

Youre crazy. She pulled it away from me. People dont eat carrion.

My brother and I exchanged a glance of regret. The hen was lost.

Each afternoon my father comes home disappointed. Not a movement, not a word, save at his command, just as nothing can happen unless it is decreed by Allah. He hits my mother. Several times I have heard him tell her: Im getting out. You can take care of those two whelps by yourself.

He pours some snuff onto the back of his hand and sniffs it, all the while talking to himself. Bitch. Rotten whore. He abuses everyone with his words, sometimes even Allah.

My little brother cries as he squirms on the bed. He sobs and calls for bread.

I see my father walking towards the bed, a wild light in his eyes. No one can run away from the craziness in his eyes or get out of the way of his octopus hands. He twists the small head furiously. Blood pours out of the mouth. I run outdoors and hear him stopping my mothers screams with kicks in the face. I hid and waited for the end of the battle.

The voices of the night, far away and near. For the first time I realize that I can hear better at night than by day. I looked up at the sky. Allah has turned on the lights. Clouds sail across the face of the big lamp. My mothers ghost appears. She is calling me in a low voice, searching for me in the darkness as she sobs. Why is she so weak? Why isnt she strong enough to hit him as hard as he hits her? Men hit. Women scream and weep.

Mohamed! Come here! Theres nothing to be afraid of. Come here.

It gave me great pleasure to see her knowing that she could not see me. A little god.

After a while I said: Here I am.

Come here.

No. Hell kill me. He killed Abdelqader.

Dont be afraid. Come. Hes not going to kill you. Come on. But be quiet, so you wont wake the neighbours.

He was in the room taking snuff and sobbing. I was astonished. He kills Abdelqader and then he cries about it.

They sat up all night, weeping silently. I went to sleep and left them sobbing together. In the morning we cried again, all of us. It was the first time I had seen a funeral. My father walked behind the old man who carried the litter, and I followed at the back, lame and barefoot.

They drop him into the wet hole. I cry and shiver. There is a mass of coagulated blood beside his mouth.

On the way back home the old man noticed the blood coming up between my toes, and spoke to me in Riffian. Whats that?

He stepped on some glass, said my father. He doesnt even know how to walk. Hes an idiot.

Did you love your brother very much? the old man asked me.

Yes, I said. And my mother loved him more. She loved him more than she did me.

All people love their children, he said.

I thought of how my father had twisted Abdelqaders neck. I wanted to cry out: He killed him! Yes. He killed him. I saw him kill him. He did it. He killed him! I saw him. He twisted his neck around, and the blood ran out of his mouth. I saw it. I saw him kill him! He killed him!

To ease the unbearable hatred I felt for my father I began to cry. Then I was afraid he was going to kill me too. He began to scold me in a low voice loaded with menace. Stop that. You cried enough at home.

Yes, said the old man. Stop crying. Your brother is with Allah. With the angels.

I hate even the old man who buried my brother.

Every day he bought tobacco and a sack of white bread. He goes somewhere far from Tangier to barter with the Spanish soldiers in their barracks. Each afternoon he comes in carrying uniforms. He sells them in the Zoco de Fuera to workmen and poor people.

One afternoon he did not come back. I went to bed, leaving my mother bathed in tears. We waited three days. I wept with her, certain that I did it only to console her. I did not ask her why she was crying. She does not love him, I know.

Next page