209 Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any request for photocopying, recording, taping or placement in information storage and retrieval systems of any sort shall be directed in writing to Access Copyright.

Printed and bound in Canada at Friesens. The text of this book is printed on 100% post-consumer recycled paper with earth-friendly vegetable-based inks.

Cover and text design: Duncan Noel Campbell, University of Regina Press Copy editor: Kendra Ward, Proofreader: Katie Doke Sawatzky

"The Negro Speaks of Rivers from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes by Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad with David Roessel, Associate Editor, copyright (c) 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

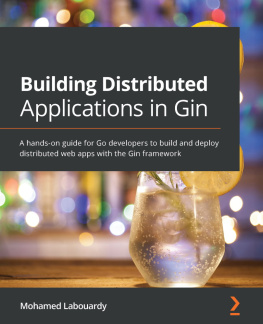

Title: Angry queer Somali boy : a complicated memoir / Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali.

Names: Ali, Mohamed Abdulkarim, 1985- author.

Series: Regina collection.

Description: Series statement: The Regina collection

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190113715 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190113863 | isbn 9780889776593 (hardcover) | isbn 9780889776609 ( pdf ) | isbn 9780889776616 ( html )

Subjects: lcsh : Ali, Mohamed Abdulkarim, 1985- | lcsh : SomalisCanadaBiography. | lcsh : Muslim gaysCanadaBiography. | lcsh : SomalisCanadaSocial conditions. | lcsh : SomalisNetherlands Social conditions. | lcsh : Gay immigrantsCanadaBiography. | lcsh : Gay immigrantsCanadaSocial conditions. | lcsh : Muslim gaysCanadaSocial conditions. | lcsh : Muslim gaysNetherlandsSocial conditions.

Classification: lcc Hhq 75.8.A45 A3 2019 | ddc 306.76/6092dc23

Saskatchewan, Canada, S4S 0A2 tel: (306) 585-4758 fax: (306) 585-4699 web: www.uofrpress.ca

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. / Nous reconnaissons lappui financier du gouvernement du Canada. This publication was made possible with support from Creative Saskatchewans Book Publishing Production Grant Program.

This work is dedicated to the one who gave me life.

This book is about addiction and recovery from trauma. It contains graphic references to physical and sexual abuse that may be disturbing to some readers.

Names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Contents

Xamar Jajab, or Broken Hamar

My grandparents were committed, wellindoctrinated communists, part of a wave of politicized African youth who emerged in the early postcolonial days following World War II. Some were trained in the finest universities of Russia, Yugoslavia, and China. All were eager to advance the ideological struggle of the hammer and sickle against the capitalist, imperialist West, which, to be fair, had raped the African continent over the preceding few centuries.

Still, socialism may have been a hard sell to nomadic Somali herders leading a subsistence life or to people struggling to stay alive on the streets of cities like Mogadishu. But my grandmother and grandfather were faithful to the teachings of Karl Marx. So faithful, that when my father inconveniently appeared in 1953, they quickly ditched him at my great-grandmothers house while they took off to pursue the class struggle somewhere in the desert.

Who could blame my grandparents though? Excitement was in the air as colonial empires collapsed. Following a military coup, Somalia finally adopted socialism as its political system in 1969. A Soviet-trained officer named Siad Barre ruled with an iron fist. Scientific socialism replaced Islamic custom and colonial laws.

By the time my father was a teenager, his grandmother, his only source of love and comfort, perished. She was his everything. She played father, mother, confidante, instructor and disciplinarian. All those functions went home to Allah with her. His whole world was draped in grief. Somalia entered unchartered waters as the 1970s dawned and my fathers parents reappeared.

Since they had been early adopters of socialism, my grandparents were granted favours by Brother Siad, our supreme leader. My grandmother became the principal of a prestigious secondary school, in Mogadishu, or Hamar as locals called it. Her own sonmy fathercouldve used a seat at this school, but grandma insisted he was not up to snuff. Her rejection of him was total.

This woman spent her youthful vigour, and his childhood, teaching nomads and their children about the modern world while he ached in vain for her affection and love. When given the chance to rectify the past, my grandmother continued to reject her son. She stayed strong in her wrong.

When my father grew into manhood, it was clear he wasnt cut out for a life of selfless brotherhood. He turned away from the countrys utopian ideals and became a firefighter in the United Arab Emirates. He left Somalia to make his fortune and settled in an industrial town named Ruwais. He began working for the national gas company. Skyrocketing oil prices filled the coffers of the Persian Gulf kingdoms and they imported millions of labourers from the newly independent states in Africa and Asia. He chose capitalism and conspicuous consumption. I saw him as a philistine, but he was in tune with the flow of history, unlike his parents. Socialism, despite its lofty promises, brought little material comfort to Somalis.

Meanwhile, Brother Siad was betrayed by the Soviets when they shifted their patronage to Ethiopia, Somalias ancient nemesis. In 1977, after a disastrous war over the Ogaden, Ethiopias Somali region, Brother Siad and his henchmen panicked and turned on their own people. As the French journalist Jacques Mallet du Pan observed in 1789, the Revolution, like Saturn, starts to consume its own children.

And so it was in Somalia nearly two hundred years later.

When my father was a youth, Somalis married young and Somali women had children early. Children were left in the care of their mothers, grandmothers, and aunts while the young women pursued the pleasures of life with their husbands.

Youthful marriages were common for various reasons, the foremost being life expectancy. Recent Somali history had been dominated by internal strife, foreign domination, and wars with its neighbours. The first ones to die were young men, so before they met their end on the battlefield, their bloodlines continuation had to be ensured. In our culture, children were raised in the mothers family but identified with the fathers clan. If a woman was left widowed, the extended family jumped into action, relieving the mother of some of the burdens.

This custom received an update when our beautiful land achieved freedom. Those sent abroad for study or work were married off before leaving. For example, my fathers first marriage, to my biological mother, was to ensure his continued, periodic return from Ruwais to Mogadishu. Clan tensions were always high, and marriage assuaged that pressure. A young woman went from her paternal home to her in-laws and had little room to consider her own personhood.

Next page