A CIP Record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Naxos Rights International Ltd.

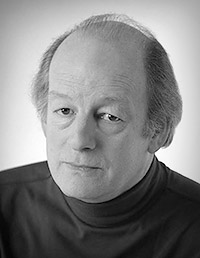

About the Author

Jeremy Siepmann is an internationally acclaimed writer, musician, teacher and broadcaster, and the editor of Piano magazine. He has contributed articles, reviews and interviews to numerous journals and reference works (including The New Statesman , The Musical Times , Gramophone , BBC Music Magazine and The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians ), some of them being reprinted in book form (Oxford University Press, Robson Books). His previous books include a widely praised biography of Chopin, two volumes on the history and literature of the piano, and biographies of Brahms and Mozart.

www.jeremysiepmann.com

Authors Acknowledgements

All books are a team effort. This one would not have been possible without the tireless support of my editors Genevieve Helsby and Anthony Short, and my wife Deborah, all of whose combination of unwavering standards, imaginative suggestions and inspiring erudition has been both a pleasure and a privilege from the outset. And last, but very far from least, I am indebted to Klaus Heymann, founder and CEO of Naxos Records, who came up with the idea in the first place.

Preface

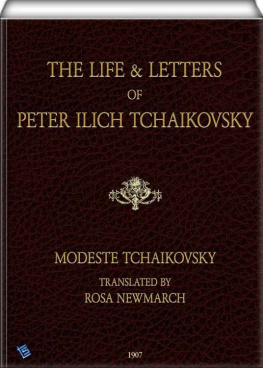

I caught the Russian bug in my teens. Voraciously, I devoured the classics of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Turgenev and Chekhov in the translations of Constance Garnett. In my twenties, I immersed myself in the Russian language and became gripped by Russian history. Curiously, only latterly was I seized by Russian music, and Tchaikovsky in particular. Hitherto, my Slavic enthusiasms had extended little beyond a near-obsession with Mussorgskys Pictures at an Exhibition and a romanticised love of Russian folk music, which I knew mainly through the seductive recreations of the gypsies. The first recording I ever recall hearing was an old 78 of Feodor Chaliapin, whom I assumed to be at least eight feet tall, singing the Volga Boat Song. The thrill of it lives with me to this day. In my thirties I belatedly discovered the operas of Glinka, and was hooked from the start. Tchaikovsky, though, was a slow burn. Slow but steady. I am a musician of predominantly Germanic proclivities, and not by natural sympathy an opera man, so it was not until my fifties that I discovered Eugene Onegin in earnest. That proved to be my gateway into the full range of Tchaikovskys multicoloured world.

Like many reared in the 1940s and 1950s, I owed the lateness of my Tchaikovskyan epiphany largely to the residue of snobbery. That climate has now changed markedly for the better. Only in the most diehard circles is he still associated with 1950s Hollywood and tacky greetings cards. His status as a great composer, in spite of his indiscriminate popularity, is now more or less universally acknowledged. His personality, however, remains both elusive and controversial, and it is with that, more than with the details of his music (which is nevertheless liberally covered), that this book is primarily concerned. It is not an act of revelation, nor does it masquerade as a work of imposing scholarship. It is envisaged as an introduction to both the man and his work, but it is also approached as a story. Its intended readership is emphatically non-specialist. No previous musical knowledge is assumed, and though the music is discussed at some length I have striven to avoid jargon and to budget for the inevitable use of a few technical terms, I have ensured that a glossary is ever ready in the wings.

The music is not treated in a separate section of the book, as in the conventional life-and-works format, but rather in a sequence of Interludes, alternating with the biographical chapters so that readers can opt, if they wish, to read the chapters as a continuous narrative, turning to the specifically musical discussions later on. The interludes, in any case, are not primarily analytical; they amount to a generically organised survey of Tchaikovskys output and also include biographical material. They can be read in any order, but they have been organised in such a way as to grow naturally out of the narrative chapters that precede them (which are themselves not without musical commentary).

While avoiding the kind of imaginary scene-setting that blights so many biographies, I have attempted to give the book some of the immediacy of a novel by allowing its protagonists wherever possible to unfurl the story in their own words. These give a far richer and more immediate portrait of both the characters and their time than any amount of subjective interpretation. That said, interpretation is inevitable: the mere selection of quotations is an act of interpretation, before commentary even begins. In a more passive sense, so too is the readers response to them. There are no absolute truths in biography beyond simple factual accuracy, though in some cases this is difficult if not impossible to determine. I have done my best in this regard.

Chapter 1

Childhood, Boyhood, Youth 18401864

A man who conducts with one hand, gripping his chin with the other to keep his head from falling off, could fairly be said to have problems. No one would deny that Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky had problems, least of all the man himself. Their nature and their source, however, remain the stuff of argument. Was he simply a neurotic? A pampered child, gifted or cursed, as the case may be, with genius? Or were his problems genetic? The arguments are nothing new, of course, and are unlikely ever to be finally resolved. Nonetheless, even without a clinically decisive explanation, the life story of this charismatic, tormented, infuriating and lovable human being holds an endless fascination for all who encounter it, just as his music has held the world in thrall throughout the century and more since his death and even his death is still hotly debated.

In few composers, and still fewer great composers, has the unity of the life and the music been more blatantly, or more defencelessly, obvious. As a man, Tchaikovsky could be devious, insincere and two-faced, though seldom if ever malicious. As a musician he was as honest as they come. It is perhaps the very directness of his music, as much as his prodigious gift for melody and orchestration, that has endeared him to so many millions. He speaks for himself, from himself and of himself, and though mercifully few others have experienced life so intensely as Tchaikovsky he speaks of emotions that are common to all humanity, and universally recognised as such. Who hears music, wrote Robert Browning in 1871, has his solitude peopled at once. Who hears Tchaikovskys music is always included. For generations he has lessened peoples loneliness all over the world. His best music says to the listener: Yes. I too have been there. And I have emerged often triumphantly, sometimes even joyfully. I know your pain; and I know your joy.