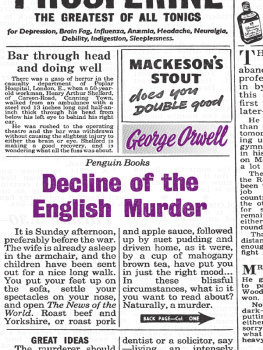

George Mikes

ENGLISH HUMOUR FOR BEGINNERS

Illustrated by Walter Goetz

Contents

About the Author

George Mikes was born in 1912 in Sikls, Hungary. Having studied law and received his doctorate from Budapest University, he became a journalist and was sent to London as a correspondent to cover the Munich crisis. He came for a fortnight but stayed on and made England his home. During the Second World War he broadcast for the BBC Hungarian Service, where he remained until 1951. He continued working as a freelance critic, broadcaster and writer until his death in 1987.

English Humour for Beginners was first published in 1980, when Mikes had already established himself as a humorist as English as they come. His other books include How to be an Alien , How to Unite Nations , How to be Inimitable , How to Scrape Skies , How to Tango , The Land of the Rising Yen , How to Run a Stately Home (with the Duke of Bedford), Switzerland for Beginners , How to be Decadent , How to be Poor , How to be a Guru and How to be God . He also wrote a study of the Hungarian Revolution and A Study of Infamy , an analysis of the Hungarian secret political police system. On his seventieth birthday he published his autobiography, How to be Seventy.

PENGUIN BOOKS

ENGLISH HUMOUR FOR BEGINNERS

Praise for George Mikes:

In all the miseries which plague mankind, there is hardly anything better than such radiant humour as is given to you. Everyone must laugh with you even those who are hit with your little arrows Albert Einstein to George Mikes

Bill Bryson is George Mikes love-child Jeremy Paxman

Mikes is a master of the laconic yet slippery put-down: The trouble with tea is that originally it was quite a good drink Henry Hitchings

Praise for How to be a Brit:

An instant classic Francis Wheen

I love it and read it cover to cover. Also has good tips for talking about the weather, not that we need them Rachel Johnson

This is the vital textbook for Brits, would-be Brits, and anyone who wonders what being a Brit really means. Pass me my hot-water bottle, please Dame Esther Rantzen

Wise and witty William Cook, Spectator

Brilliantly comical Pico Iyer, The New York Times

Full of the very best advice that any would-be Brit should need (and for those of us who have forgotten exactly how it is to be ourselves) its a jolly good read Telegraph

Very funny Economist

Part One:

THEORY

Does it Exist?

English Humour resembles the Loch Ness Monster in that both are famous but there is a strong suspicion that neither of them exists. Here the similarity ends: the Loch Ness Monster seems to be a gentle beast and harms no one; English Humour is cruel.

English Humour also resembles witches. There are no witches; yet for centuries humanity acted as though they existed. Their cult, their persecution, their trials by the Inquisition and other agencies, went on and on. Their craft, their magic, their relationship with the Devil were mysteries of endless fascination. The fact that they do not exist failed to prevent people from writing countless books indeed libraries about them. Its the same with English Humour. It may not exist but this simple fact has failed to prevent thousands of writers from producing book upon book on the subject. And it will not deter me either.

We shall have to spend a little time on definitions. The trouble with definitions is that although they can be illuminating, witty, amusing, original and even revolutionary, there is one thing and perhaps one thing only which they cannot do: define a thing. This is more true in the case of humour than in the case of anything else. We shall come to that later. But we shall still have to try to answer such questions as: What is English? What is Humour? What is English Humour? Is English Humour the humour of a nation or just a class? What have cockney humour and Evelyn Waugh in common?

Before going into details, I should like to say a few words in general. If English Humour is the sum total of all humorous writing that has appeared in the English language then, in that sense, English Humour does exist. So do Bulgarian, Finnish and Vietnamese humours. England or Britain, or the British Isles has produced eminent and brilliant funny men from Chaucer, through Dickens, Oscar Wilde and W. S. Gilbert to P. G. Wodehouse and Evelyn Waugh. And, if the question is whether the English people can laugh and make good jokes, then again the answer is yes.

But this is not what champions of English Humour have in mind. They allege that the English possess a sense of humour which is specifically English, unintelligible to, and inimitable by, other people and needless to add superior to the humour of any other nation. That is a debatable point. But a point worth debating.

In other countries you may be a funny man or a serious man; you may love jokes or hate them; you may think clowns and jesters the cream of humanity or crushing bores. You may, of course, have the same views in Britain, too. Yet Britain is the only country in the world which is inordinately proud of its sense of humour. In Parliament, in deadly serious academic debates, even in funeral orations, Shakespeare is less often quoted than Gilbert or Lewis Carroll. Every after-dinner speech be it on the sex-life of the amoeba must end with a so-called funny story. You may meet here the most excruciating bores, the wettest of blankets, the dreariest sour-pusses all of whom will be extremely proud of their sense of humour, both as individuals and as Englishmen. So if you want to succeed indeed, to survive among the British you must be able to handle this curious and dangerous phenomenon, the English Sense of Humour; to stand up to it; to endure it with manly or womanly fortitude.

In other countries, if they find you inadequate or they hate you, they will call you stupid, ill-mannered, a horse-thief or a hyena. In England they will say that you have no sense of humour. This is the final condemnation, the total dismissal.

On the following pages I shall explain what English Humour is, i.e. what it is if it exists at all; what the English think it is; how to be humorous in England; what insults and insolence one must pocket lest one should be declared humourless, i.e. not a member of the human race.

If its Good its English

My first suspicion that there is no such thing as English Humour arose early. A few weeks after my arrival in 1938 a few people told me that I had a very English sense of humour. That was obviously a compliment. Even more obviously it was utter nonsense. I had just arrived from Hungary where I had been bred and born; I had never read one single book in English because my English was not good enough; I had seen altogether three Englishmen in my life, none for longer than for five minutes. How, where and why should I have acquired an English sense of humour?

I observed, however, that only my good jokes were greeted with this high praise. No dud joke, witless observation or silly pun ever merited the comment. No one ever said: Your sense of humour is absolutely lousy but, I must say, its very English. The pattern about my humour followed the general pattern: if it was good it was English; if it was abominable it was foreign.

But soon enough contrary doubt assailed me, too. Perhaps, after all, there was a special English sense of humour. I heard the following joke in those early days.

Next page

George Mikes

George Mikes