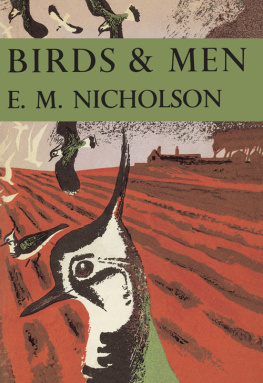

JAMES FISHER M.A.

JOHN GILMOUR M.A.

SIR JULIAN HUXLEY M.A. D.SC. F.R.S.

L. DUDLEY STAMP C.B.E. D.LITT. D.SC.

Photographic Editor

ERIC HOSKING F.R.P.S.

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalist. The Editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native fauna and flora, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

To William Homan Thorpe

E. A. ARMSTRONG will be already known to the readers of the New Naturalist Series as the writer of one of the most important monographs on a single species of animal, his famous study, The Wren, published in 1955.

Wide scholarship and talents have fitted him uniquely for the authorship of The Wrens most unusual sequel. We use the word unusual deliberately because his The Folklore of Birds is a most extraordinary book. It could only have been written by a scholar with a deep understanding, not only of ornithology, but of social anthropology, psychology and religion.

Armstrong has selected an assemblage of well-known birds upon which to base what he describes in his sub-title as An enquiry into the origin and distribution of some magico-religious traditions. He has set himself the task of revealing the general principles that underlie the evolution and diffusion of beliefs and symbols. With the scientists eye and the scientists methods of analysis and investigation he has examined the development of myth and ritual with originality and ingenuity. It is hard for us to make a choice from the multitude of those odd and interesting facts which Armstrong cites in this book, to bring to the readers attention. Customs such as breaking the wish-bone are explained with new and brilliant reasoning. Every kind of naturalistand archaeologists, folklorists and ornithologists are all naturalistswill follow with interest his compelling studies of the origins of such beliefs as those concerning weather-prophet birds, and of such fables as that of the generation of the barnacle goose from barnacles.

We do not know of any previous attempt of such importance to trace beliefs concerning birds as far back as possible in time, and to identify the cultures in which they must have originated. Armstrong has examined groups of folk-lore beliefs, it seems to us, in just the same way as an archaeologist examines a series of artifacts; and we know of no other scholar who has given folk-lore just this sort of treatment, classifying beliefs and notions in a system based upon the eopchs in which they originated.

Armstrong has, indeed, combined the facts derived from archaeology with oral and literary traditions, to illustrate the origins and significance of much of the current folk-lore of birds. Some of the magico-religious myths and cults, of which these fragmentary traditions are the relics, prevailed in the past throughout most of northern Europe and Asia and in some areas of North America. Such beliefs were carried about the world in the streams of culture, and their travels are often illuminated by graphic motifs and imagery, much of which is reproduced in the pages of this book, and some of whichfrom the old Stone Age to modern timescan be held to be artistic masterpieces.

Promoting, as it does, our understanding, both of man and nature, this is a book that we are proud to sponsor.

THE EDITORS

THE collectors of British folklore who were active in Victorian times and into the beginning of this century were just in time to record much of interest which has now disappeared. A few enthusiasts, notably the members of the Folklore Society and contributors to its journal, keep alive an interest in the subject, yet the study of folklore is currently regarded more as a recreation for the dilettante than as a respectable occupation. This may be due, in part, to the authors of many English books on the subject being content with presenting a pot-pourri of Victorian gleanings. Elsewhere, notably in Eire, Finland and Sweden, and at some universities in the United States, folklore research is conducted by highly trained scholars whose work has been an inspiration to their countrymen and a valuable contribution to mans understanding of his past. Inspired by the ambition to gather up the fragments that remain that nothing be lost they have rescued much material from oblivion and, in some realms, especially the study of the folk-tale, laid solid foundations for further work. The increasingly rapid spread of industrialism and the standardisation of modes of thought due to modern means of communication are now eliminating ancient beliefs and practices over most of the world and consequently the geographical distribution of folk tradition is becoming obscured. The attrition of ancient folklore in this country has been particularly severe and its last strongholds, such as the Hebrides, are now under assault. It is but small consolation to hope that radio and television, which are doing so much to standardise thought, may eventually arouse interest in folklore as they have done in archaeology.

An essay on British bird folklore cannot be a review of recent field work, partly because of the decay of such folklore but also owing to the absence of intelligent public interest in collecting it, though high appreciation must be accorded the effective labours of workers in Ireland and North Britain. The opportunity for gleaning folklore is rapidly passing but this makes it all the more important to try to assess the significance of our traditions in the hope of stimulating a more just appraisal of what folklore may teach us concerning the mental and spiritual interests of our forefathers. Those who know something of the rock whence they were hewn will order their present affairs with greater wisdom. I am more optimistic than some archaeologists in their attitude to the thought-life of folk who lived long ago. Professor Gordon Childe, for example, has expressed the opinion that the content of religious belief of pre-literate peoples is irretrievably lost. We are justified in believing that folklore, in alliance with other sciences, especially archaeology, anthropology and comparative religion, can give us some insight into the spiritual culture of prehistoric peoples as well as shed light on the beliefs and practices of communities, and the psychology of individuals, up to and including, our own times.

The conviction underlying this survey is that it is possible to analyse a group of beliefs current in a modern, highly mechanised society, in such a way as to identify particular traditions, with a considerable degree of probability, as originating during certain epochs and belonging to specific culture-complexes. I would not claim that the evidence marshalled in support of this belief is as complete and cogent as might be desired but I hope that the feasibility of such an approach has been demonstrated and that others, more adequately equipped, may apply similar methods to other realms of folklore. I have no doubtand I trust that I can carry the reader with me in thisthat most ancient beliefs which have come down to us and seem now not much more than flotsam and jetsam on the tide of modern mans thought were once closely integrated into the spiritual life of earlier communities. As kindred studies of this type proceed it should be possible to date more accurately the cultures to which certain ideas belong and so to establish a stratigraphy of the non-material aspects of mans past.