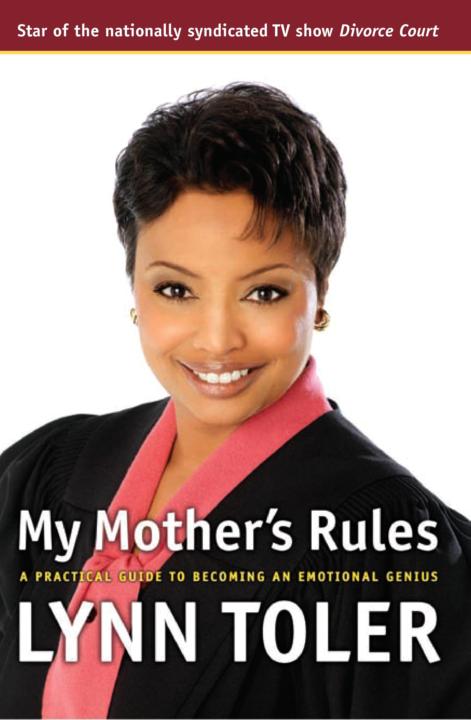

My Mother's Rules

My Mother's Rules

A Practical Guide to Becoming an Emotional Genius

LYNN TOLER

CONTENTS

Chapter i

Chapter 9

Chapter 23

Chapter 41

Chapter 55

Chapter 71

Chapter 83

Chapter 95

Chapter 105

Chapter 117

Chapter 125

Chapter 137

Chapter 145

Chapter 153

Chapter 163

To my sister, Kathy

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND AUTHOR'S NOTE

I'd like to thank Jeff Lucier for reading the first draft, which could not have been easy, and giving me such great feedback.

I'd also like to thank Jayne and Chris Eiben for all of their help. They gave me great direction and unbelievable support.

Thanks, too, to Matthew Hatchadorian. He was the first one to tell me I should run for judge.

And last, but certainly not least, I'd like to thank my husband, Eric Mumford, whose unwavering and occasionally irrational belief in me helped me turn so many of my dreams into reality.

In this book, I tell many stories based to some extent in experiences I have had serving on the bench. Although they are all a matter of public record, I massaged the facts in order to avoid causing any undue embarrassment. Thrown chairs became broken windows; brothers became cousins; and names most definitely were changed. However, I took special care not to change the instructive dynamics of these situations.

One:

The Proper Emotion

No one really got excited until the day they found me sitting in the closet.

"Lots of kids play in the closet," I told my mother, suggesting that she may have simply misinterpreted what she saw.

"Sitting in the closet wasn't the problem," she said. "We only started worrying when we couldn't get you out." My mother then paused, as she sometimes does, for a little dramatic effect. Lowering her voice and leaning into me, she said, "Do you realize you told me you couldn't get out because it wasn't safe?"

That was the comment, I now understand, that set off my mother's alarm and sent me to the doctor so Mom could face her greatest fear.

While I admit the closet thing seems a bit odd, I do have an explanation. Possessed of a predisposition to panic, I have never been a brave soul. Wild, irrational worry comes naturally to me. I was, it appears, designed that way. I think it is in my genes.

My father, on the other hand, was a little nuts-a man who, had he been born in this day and age, most surely would have been medicated. Volatile, unrelenting, an incident poised to occur, Daddy was an ongoing event. At our house, a mispronounced word could have us running for our lives. A dirty carpet could lead to gunplay.

This, of course, was not the ideal environment in which to raise a flighty kid. Unlike my sister, Kathy, a sturdier child who took our father in stride, I could not separate the things Daddy did from the way the rest of the world worked. I thought the entire universe rocked and rolled with the same abandon as did our living room, an outlook which made camping out with clothes seem like a reasonable thing to do.

I would, however, like to point out that I am quite recovered now. I haven't had the urge to reside with coats and boots for years. In fact, my current state of mental health is a source of great pride for me. Though once unable to rationalize my way out of a closet, I am now a woman to whom others go for good advice and calm. Once the first to run when trouble arose, I now regularly chase storms.

How did I do it, you ask? What wisdom did I acquire that not only got me out of the closet, but now allows me to feel at ease almost anywhere I go?

Neither therapy nor meditation authored my eventual calm. Pop psychology was not employed, nor were years of getting the real thing. The answer is simply this: I have an extraordinary mother, a woman who is master of an art most people don't even see as a skill. Toni Toler, the woman who brought me into this world-not once, I contend, but twice-is an incredible emotional manager. She has this amazing ability to step away from herself and decide how she will feel. It is a talent most people fail to recognize, not to mention understand. It is also a talent, I now know, she purposely passed on to me.

My mother's unusual gift is a bit difficult to describe. In fact, I did not fully understand it myself until I became a judge. That's right-the little girl who once took up residence in a closet eventually took the bench. For eight years I ran a municipal court, a place often referred to as the court of the common man. Municipal court is the judicial home of traffic tickets, evictions, and barking dogs. It's where people go to discuss bad hair cuts, loud parties, and unpaid rent. Feuding neighbors are often sent there to explain the lump on the other guy's head. In short, a municipal court is where regular people go when they get caught doing irregular things.

Of course, it isn't all small stuff. Municipal courts see a lot of domestic violence, drunk driving, and assault charges. Every once in a while we'll see negligent or vehicular homicide cases as well. But these things do not take up the bulk of a municipal judge's day. For the most part, municipal judges see familiar misfortune and commonplace concerns. We see the average individual, at his worst and in volume.

This unique opportunity helped me to learn a great deal about people in general. I now know, for instance, that regular people don't typically do irregular things because they are immoral, criminal, or stupid. I have discovered, instead, that people most often get into trouble because they lose sight of the Boo-pound invisible gorilla. Problems arise when we, the general public, fail to keep our emotions in full view.

Most people are not, I have realized, emotionally well-practiced. We tend to misunderstand our fears and misinterpret our desires. We act when we ought to sit still; we feel when we should instead think, and in the end, this allows our emotions to handle us as opposed to us handling them.

Worse yet-though we are quick to rush into treatment, rehabilitation, or analysis when our emotional boats begin to sink-the ongoing, everyday preparation we receive for living our emotional lives tends to be very haphazard. While we're anxious to acknowledge how we feel these days, that seems to be about all we are willing to do. Instead of trying to adjust how we feel, so we can do something that (at least) resembles the right thing, we act upon the emotion at hand as if we have no other choice.

This got me thinking.

If my mother's way of doing business could rescue someone as emotionally mismanaged as me, could her know-how help others who make more minor emotional mistakes? Could my mother's wisdom somehow be boiled down, clarified, and passed on in some useful form?