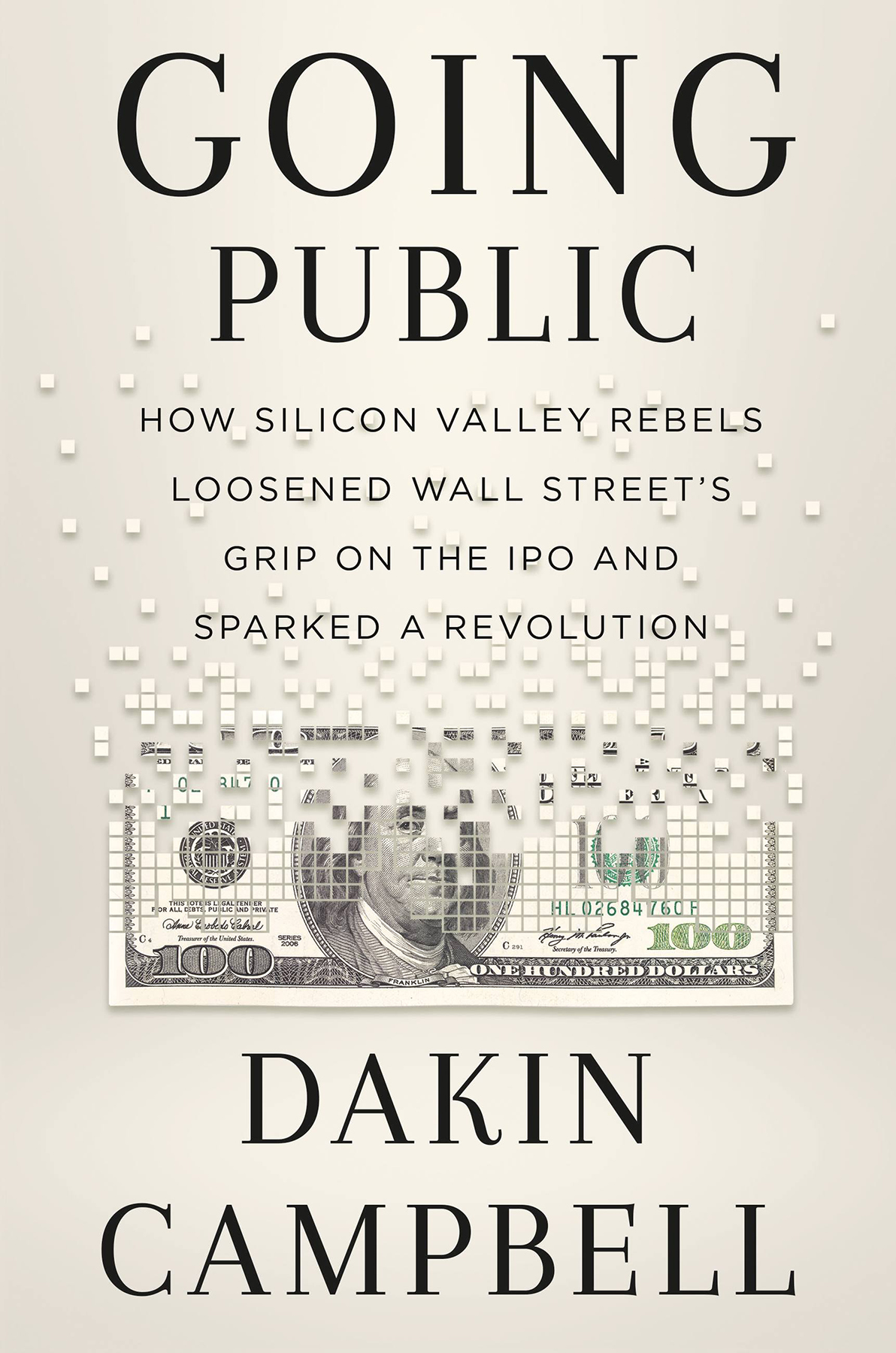

Cover design by Sarahmay Wilkinson. Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Twelve is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing. The Twelve name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

I first started thinking critically about IPOs during the summer of 2019 as the real estate startup WeWork prepared to sell shares to the public. A financial writer for more than a decade, I had a passing knowledge of how investment banks worked with private companies entering the public markets for the first time. It wasnt until my editors at Insider scrambled a team of reporters to dig into what was happening at WeWork that I got my first good look at the process.

I soon learned that startup founders, venture capitalists, and even some bankers had been raising questions for years about how IPOs were being handled. By the time of WeWorks planned offering, Spotify and Slack had already chosen an alternative approach to listing their shares. Venture capitalist Bill Gurley was loudly banging his drum for other startups to follow suit. Change was in the air.

That didnt make it any easier to understand what was really happening. IPOs were a world within a world, a corner of Wall Street made up of its own characters, customs, and regulations that was nearly as hard to pull apart as the mortgage bonds that sparked the global financial crisis. As WeWorks listing quickly slid off the rails, I set out to learn as much as I could.

I devoured news reports, perused research papers, and sought out startup executives, investors, bankers, and lawyers. By the time I was done, Id spoken to roughly 75 people over more than 150 interviews. Some of those agreed to speak on the record, many of them with the belief that their comments would help readers to understand and appreciate their perspective, and their voices are reflected in the text.

Most of them, however, asked for anonymity to describe private conversations. I have tried to verify their accounts from other sources who were in the room, news reports, official documents or government filings, text messages, videos, or PowerPoint slides, to name just some of the resources I relied upon. In a few cases, recollections contradict one another. I have been thoughtful about coming to an accurate version of events. A reader shouldnt assume that someone spoke to me just because I describe that persons thinking. In numerous cases, I reconstructed what an individual thought by speaking to others who spoke to them directly or were otherwise in a position to know.

Throughout the book, I have avoided adding unnecessary analysis to the text. My hope is that the reader will come to his or her own conclusion based on how the narrative unfolds and the specific details of each transaction. I readily acknowledge that there is a fierce debate swirling around the current IPO process and the importance of various actors such as investment banks to the process. This book wont settle that debate, but I hope it can add to the dialogue by bringing readers into the rooms where big decisions are being made.

I hope you leave this book with a richer and more nuanced understanding of IPOs, how Wall Street and Silicon Valley are jockeying for supremacy over the process, and what it would mean to most efficiently funnel capital to the companies doing the most to drive economic innovation.

Last, I hope you like reading the story as much as I enjoyed discovering it.

Thanks for reading.

Dakin Campbell

April 2022

Apple Computer, Cupertino, 1980

O n a mild December day in 1980, Steve Jobs made his way across San Francisco to an office building that rose above the citys financial district. Passing through the terra-cotta archways that gave the facade a neo-Gothic look, Jobs sought out the office of Hambrecht & Quist (H&Q), a small investment bank with offices on an upper floor.

Jobs was the CEO of Apple Computer, a leader in what was then the budding business of making desktop computers. Apples revenue had climbed past $117 million during the fiscal year that had ended in September, more than the entire industrys haul just three years earlier.

For months, Jobs had been preparing Apple for its initial public offering, the first sale of stock to mutual funds and other public investors. The CEO had come to the landmark Russ Building for one of Apples last acts as a private company: negotiating with his bankers over the price of the shares Apple would sell.

Months earlier, Jobs had selected Morgan Stanley and Hambrecht & Quist to manage Apples IPO. Hambrecht & Quist was an early investor in Apple. Jobs was showing loyalty to an early backer by insisting on the location even though Morgan Stanley was larger and more powerful.

As a former computer hacker known for wearing ripped denim jeans and tie-dyed t-shirts, Jobs arrived casually dressed. He joined a group of bankers in suits and ties gathered around a couch in a large office that belonged to George Quist, whose name was on the door. The other named partner, William Hambrecht, was also there, alongside the team from Morgan Stanley.

Jobs and his bankers had been holding weeks of meetings in what was known as a roadshow, talking to investors about their interest in Apple shares. The bankers initially thought to sell shares at $14, but as the investor conversations continued and orders poured in, they realized they could increase Apples share price without sacrificing investor interest. The question was by how much.

The Morgan Stanley bankers walked Jobs through the investor orders, collected in something known as an order book. As they did, Hambrecht later recalled, Morgan Stanley recommended a price of $18.

Jobs sat there silently and listened. He spoke when the bankers were finished.

Now, youre telling me that you want to sell the stock at eighteen dollars a share? Jobs said.

Yes, thats our recommendation, came the answer.

You know, Jobs said, some people have told me they think it might open up maybe as high as twenty-seven or twenty-eight.

Jobs was referring to the price that he thought Apple shares would fetch when they began trading on the stock exchange. He knew that Apple wouldnt directly benefit when its stock price rosethe company would have already sold its stock and collected the proceeds. For that reason, he was interested in capturing as much of the price gain as possible in this meeting, when it would mean more money in Apples accounts.