Chapter 1

Odyssey

1 One of the three brothers had a golden sling, and with it he could throw a stone up to the sky: it would almost touch the clouds.

1 There are several versions of the Inca origin story. Parts of different versions appear in Harold Osborne, South American Mythology, (Feltham, Eng.: Hamlyn Publishing Group, 1968).

These are words from a story that the Incas told about their own origins. At first, it seemed a good way to start: what better way is there to begin to discuss the quipus of the Incas than by using an Inca story about their own beginnings. But right away we must pause; the story was spoken in Quechua, recorded in Spanish, and translated into American English. Once aware of this, we cannot go further until we answer the question, How do we know anything about the Incas?

The Spanish recorded the Inca origin story more than four and a half centuries ago. The Incas were a culture, a civilization, and a state. That is to say, the word Inca, as we use it, applies to particular forms of human association. The land that the Incas once occupied is today all of Peru and portions of Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. When the Spanish arrived to conquer, the Inca state had existed for about one hundred years. Within thirty yearsthe number of years generally used to designate one human generationInca civilization was destroyed.

The Incas did not write as we usually understand that activity. For written accounts of Inca culture, we must turn to the sixteenth-century Spanish of soldiers, priests, and administrators. Yet, the culture of the Spaniards of that time is remote from our own. We do not share with them, for example, a real fear of the devil, even if we are part of the tradition that invented him. And the devil, together with many other cultural predispositions, figured largely in Spanish discussions of the Incas. To make matters worse, the Spanish got their information almost exclusively from deposed Inca bureaucrats. They were a special and numerically small part of a population estimated at somewhere between three and five million people. Whatever we may or may not have in common with sixteenth-century Spaniards, they shared close to nothing with the Incas. We can make sense out of Spanish accounts only in terms of our framework, and the Spanish, for their part, rendered what the Incas said from inside a Spanish framework. As a result, written accounts are distorted as they pass through this route: one culture (Inca) is interpreted via a second culture (Spanish), which is interpreted via a third culture (American), four hundred and fifty years later.

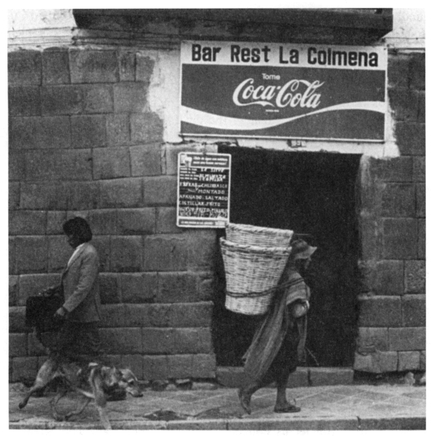

Luckily, there is a source of knowledge in addition to writing. Walking one day in the streets of Cuzco, once the capital of the Inca state, we saw an Inca wall, topped by a Spanish wall, on which was hung a Coca Cola sign. What we saw tells a good deal about the relationship between three cultures. But let us concentrate on the Inca wall. The Spanish could hear about the wall, and they could see it and touch it. We also can see it and touch it, but we cannot hear about it from the Incas. Nevertheless, the Inca wall, and other things that they made and that have survived, provide us with a direct way of knowing about the Incas.

Using material things as a source of knowledge does not, however, do away with distortion. Walls of some sort occur in every culture. This can lead us to think that wherever they occur they have the same meaning. They do not. Nevertheless, with due caution, it is reasonable to assume that walls, wherever they are found, serve a roughly similar purpose. But there is another more difficult problem in understanding material evidence. There are some things in one culture for which there are no counterparts elsewhere. When this happens, understanding becomes even more difficult for someone outside the culture. For example, native Australians had no counterpart of the airplane. It was at first difficult for them to understand that people flew through the air in metal containers. And the problem increases when an attempt is made to know about a culture that is remote in time as well as in space.

We wish to understand the quipus made by the Incas. But unlike walls, there were no counterparts of quipus in sixteenth-century Spanish culture and there are none in our own experience. A quipu is a collection of cords with knots tied in them. The cords were usually made of cotton, and they were often dyed one or more colors. When held in the hands, a quipu is unimpressive; surely, in our culture, it might be mistaken for a tangled old mop. For the Spanish, the Inca quipu was the equivalent of the Western airplane for native Australians. For us, the problem is compounded by a separation of four and a half centuries. Before rushing ahead to where touching, seeing, and thinking about quipus led us, a context for them must be provided. To do this, we call upon a Spanish witness.

2 Spanish writers shared a cultural framework, but there were very important individual differences. Today there is general agreement on which of the writers are relatively reliable. Cieza de Len was perhaps the most reliable. He was a good observer and a careful listener, and he was the first person to write about quipus. Our knowledge of what the Spanish understood about quipus is increased only a little by going to other early writings, for Cieza understood more than his contemporaries, and many later writers simply copied from him.

The writings of Cieza seized and held our attention from the start of our studies. There are minor reasons and one major reason for this. Cieza was in Inca territory only fifteen years after the conquest; this alone commends his work. He saw things that others who followed cannot have seen, and he spoke with people who were adults at the apogee of Inca power. In addition, Cieza is an able writer. His choice of vocabulary, his ability to put things concisely, his conscientious attempt to weigh evidence, and his respect for the intelligence of the reader, set him apart as much as does his being there before others.

But the major appeal of Cieza centers on what leads us to use the word odyssey to describe his work. At one level, an odyssey simply means a journey; that clearly applies to Cieza. In a broader sense, an odyssey is a quest or a search that may or may not involve travel through real space. It is important that the term odyssey in this second sense also applies to Cieza. In literature, the odyssey is often a self-conscious search for the self. Ciezas quest is different: he is not looking for himself, but rather for the substance of the victims of conquest. That Cieza thought of the Incas as victims is clear; as he says, wherever the Spanish have passed, conquering and discovering, it is as though a fire had gone, destroying everything it passed. Although he was a party to conquest, the victor is of less interest to him than the vanquished.

2 The first part of the writings of Pedro Cieza de Len was published in 1553, the second part in 1880, and the third part was published as late as 1946. The best English translation of the first two parts is by Harriet de Ons. It is in Victor Wolfgang von Hagen, ed., The Incas of Pedro de Cieza de Len (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959). Our English citations from the works of Cieza derive largely from the Harriet de Ons translation, but Spanish versions have been consulted where there is a question of interpretation. There are two major sources on Ciezas life. They are: Marcos Jimenz de la Espada, Prlogo de la Segunda Parte de la Crnica del Per de Cieza de Len, vol. 5 (Madrid: Biblioteca Hispano-Ultramarina, 1880); and Miguel Maticorena Estrada, Cieza de Len en Sevilla y su Muerte en 1554, Anuario - de Estudios Americanos 12(1955): 61573. In his editors introduction to the Harriet de Ons translation, von Hagen provides a background of Ciezas times and a summary of his life. A study of the literary aspects of Ciezas writings is found in Pedro R. Len, Algunas Observaciones Sobre Pedro de Cieza de Len y la Crnica del Peru (Madrid: Biblioteca Romnica Hispnica, 1973). This book also contains a rather complete bibliography on the work and life work of Cieza.