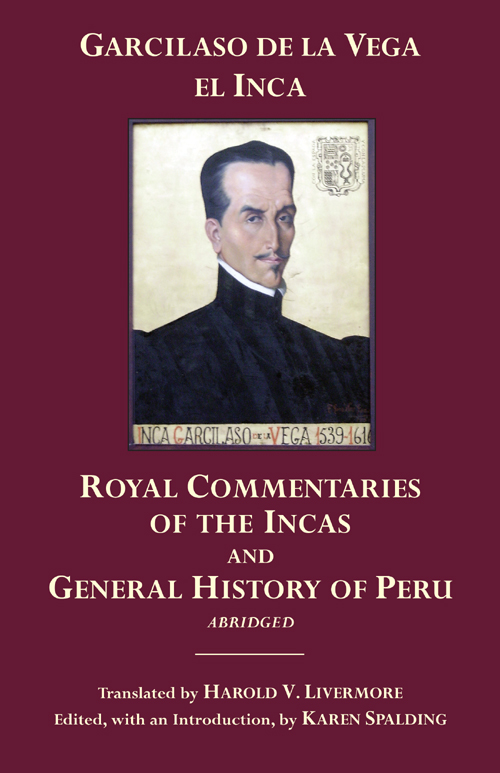

Royal Commentaries of the Incas

and General History of Peru

Abridged

Garcilaso de la Vega, El Inca

Royal Commentaries of

the Incas and General

History of Peru

Abridged

Translated by

Harold V. Livermore

Edited, with an Introduction, by

Karen Spalding

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2006 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

18 17 16 15 14 13 2 3 4 5 6 7

This translation was originally published by the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States, which has granted a non-exclusive and limited license of its rights in the work to this Publisher. New Introduction, Further Reading in English, Notes, and Index copyright 2006 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

For further information, please address:

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, IN 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Abigail Coyle

Text design by Carrie Wagner

Composition by William Hartman

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vega, Garcilaso de la, 15391616.

[Comentarios reales de los incas. English]

Royal commentaries of the Incas and general history of Peru : abridged / Garcilaso de la Vega, El Inca ; translated by Harold V. Livermore ; edited, with an introduction by Karen Spalding.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-87220-843-8 (pbk. : alk.paper)

ISBN-10: 0-87220-843-5 (pbk. : alk.paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-87220-844-5 (cloth : alk.paper)

ISBN-10: 0-87220-844-3 (cloth : alk.paper)

1. Incas. 2. PeruHistoryTo 1548. 3. Indians of South AmericaPeru. I. Livermore, H. V., 1914- II. Spalding, Karen. III. Title.

F3442.V3713 2006

985.01dc22

2006016436

ePub ISBN: 978-1-62466-156-3

Felipe Fernndez-Armesto, Columbus on Himself.

Felipe Guaman Poma De Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government. Edited and Translated by David Frye.

Bartolom De Las Casas, An Account, Much Abbreviated, of the Destruction of the Indies. Edited, with Introduction, by Franklin W. Knight, Translated by Andrew Hurley.

Bernal Diaz Del Castillo, The True History of the Conquest of New Spain. Translated, with an Introduction and Notes, by Janet Burke and Ted Humphrey.

Michael A. Malpass, Daily Life in the Inca Empire.

Titu Cusi Yupanqui, History of How the Spaniards Arrived in Peru. Edited and Translated by Catherine Julien.

This edition is intended for people who enjoy going to strange and exotic places and getting to know new and unfamiliar societies and cultures. You may already be traveling as a member of a college course, or you may be preparing to leave for one of these exotic places. Most travelers get more out of exploring a new and strange country if they have access to a guide who knows the world that is foreign to the traveler, and there is no better guide to the Andean past than Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. The sixteenth-century author of the texts presented here dedicated his life to explaining the history and culture of his native Andes to his Spanish contemporaries.

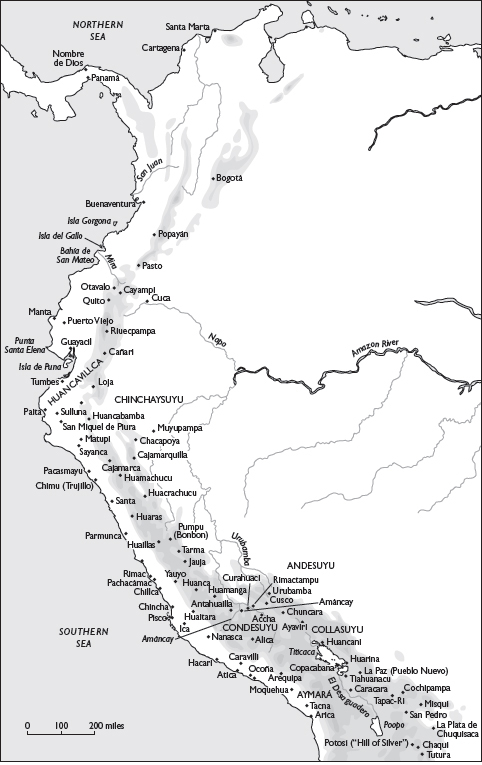

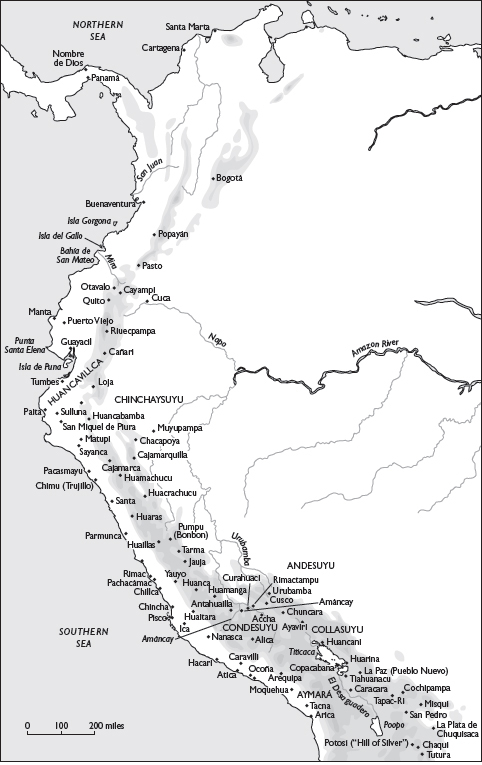

The Andes are one of the three highest and most mountainous areas of the globe (The others are the Alps and the Himalayas). For centuries, Andean societies have thrived in the mountain slopes, high valleys, and mile-high plains. This beautiful and difficult landscape reaches heights that people who live in lower, flatter regions often think of as fit only for mountain goats and ski resorts. In Royal Commentaries of the Incas and General History of Peru Garcilaso provided a guide to the lands and peoples of the Inca state, whose reach extended from what is today northern Ecuador to Chile and northeastern Argentina.

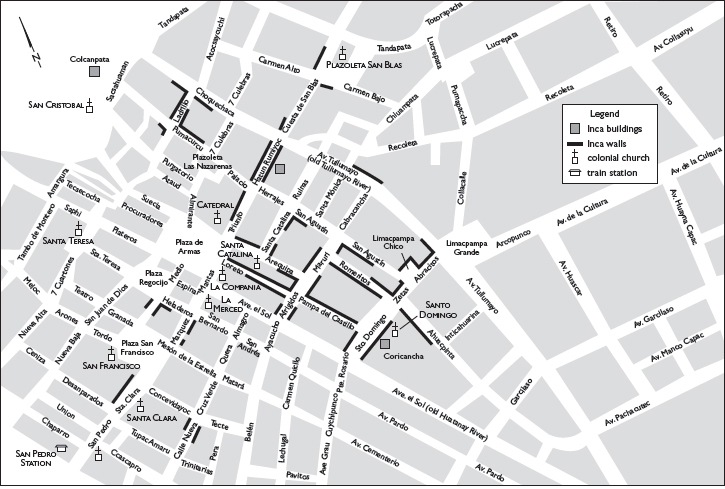

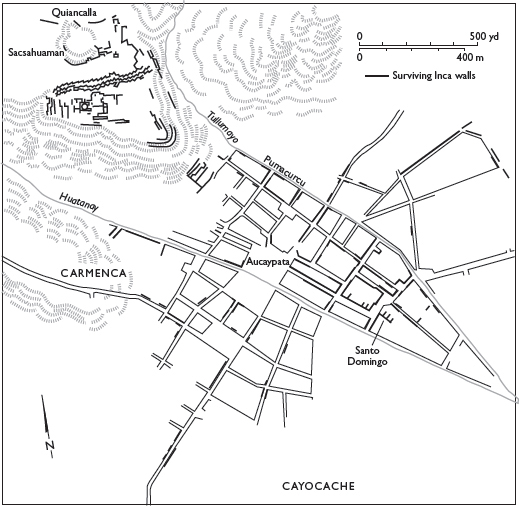

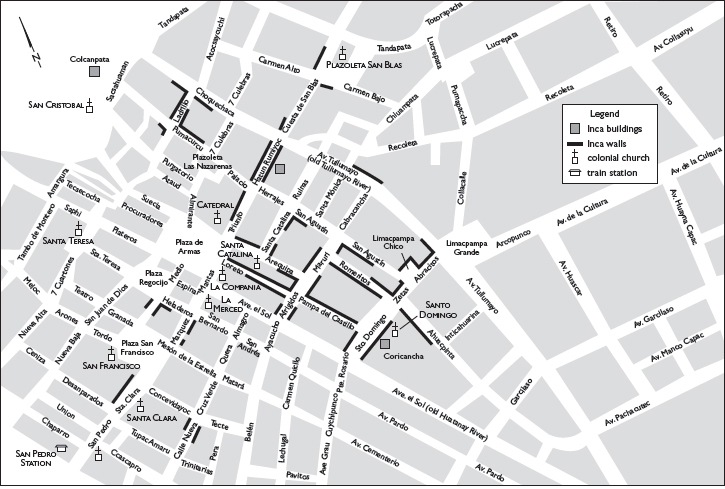

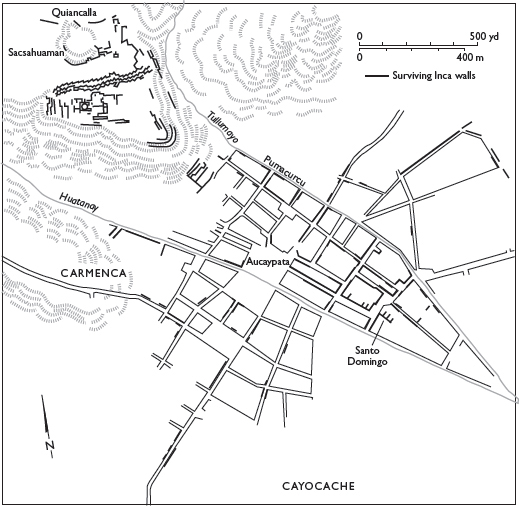

Garcilaso was born in Cusco, the center and capital of the Inca empire, in 1539, less than a decade after the Spaniards entered the Andes in 1531. His early life was shaped by two conflicts: the battle among the Spaniards over who would control Peru and its riches, and the ongoing struggle between Spaniards and the Incas, who fought back against Spanish conquest. The conflict among the Spaniards for control of the Andes ended in 1554, but the Inca resistance did not end until 1572, forty years after the Spanish arrived.

When the Spaniards marched into the Andes, they stepped into a struggle for control of the Inca state. They captured the leader of the victorious faction in Cajamarca, in the north of Peru, and killed him a year later, after he provided the Spaniards with an immense ransom. The Spaniards next fought their way south to Cusco, where they joined forces with Manco Inca, a member of the defeated faction. In 1533, Manco Inca was crowned in a ceremony in which the Spaniards occupied the position of valued allies. During the ceremony the Spanish read the requirimiento, an odd bit of legalistic bombast that demanded that the hearers acknowledge, without question, the supremacy of the Christian God in heaven and the Spanish monarch on earth. Manco embraced Francisco Pizarro, the leader of the Spanish force, and with his own hand offered drink to [Pizarro] and the Spaniards.

The records from this period suggest two very different stories that have been mixed together. Pizarros actions were those of a victorious conqueror who, in his capacity as governor, proceeded to organize and consolidate his victory, while at the same time it appears that Manco was attempting to rebuild the complicated alliances that supported the Inca rule from Cusco. I suspect that Manco saw the Spaniards and their actions, violent and brutal as they were, as tools for the reprisals that he expected to make in the process of reestablishing the authority of Cusco.

But the two stories soon clashed, and by 1536, Manco decided to rid himself of his increasingly violent allies and called upon his subjects throughout the still-unsettled Inca state to join him in expelling the invaders. Manco withdrew from Cusco to meet the warriors who responded to his call, and his forces surrounded the city and attacked the Spaniards inside. The siege lasted for months, and the Indians came close to eliminating the invaders, but the arrival of additional Spanish forces by both land and sea and the exhaustion of the storehouses of the Inca state after years of war and disruption forced the Indians to withdraw into the rough lands leading into the jungle regions behind the capital. There Manco and his supporters established a court-in-exile from which they harassed both the Spaniards and the Indians who submitted to the new rulers.

Even before the Incas withdrew, however, the Spaniards began to fight among themselves. A power struggle between Pizarro and his partner, Diego de Almagro, ended with Almagros capture and execution in 1538. That event marked the beginning of endemic conflict between Spanish factionsand later between the Spaniards and royal authoritythat went on until 1554. Almagros death was followed by Pizarros assassination in 1541 by the supporters of Almagro in revenge for the death of their leader, and the Almagrists were defeated in turn by the Spanish governor sent to investigate reports of turmoil in Peru, while a group of Manco Incas warriors watched the Spaniards battle one another from the surrounding hills.