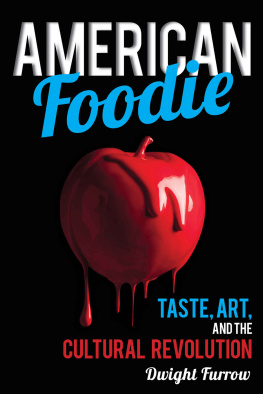

American Foodie

American Foodie

Taste, Art, and the Cultural Revolution

Dwight Furrow

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Furrow, Dwight, author.

American foodie : taste, art, and the cultural revolution / Dwight Furrow.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-4929-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-4930-1 (electronic)

1. FoodUnited StatesPhilosophy. 2. Dinners and diningUnited States. 3. Food preferencesUnited States. I. Title.

TX360.U6F87 2016

394.1'20973dc23

2015027903

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Preface

My love affair with food began when, as a nineteen-year-old, I was invited to a family meal at the home of an Italian friend. As the conversation, in all its twists and turns, always returned to the food and its quality, it was apparent that, for them, food was more than fuel or a pleasant diversionit took on aspects of the sacred, something to be cherished in itself as a potent symbol of the good life. Since that memorable meal I have gradually become convinced that nothing else in life gives us so much ongoing pleasure as the food we love, so I was struck, when drinking deeply from the history of philosophy and teaching it for many years, by the fact that great thinkers largely ignore food as something worthy of thoughtful attention. Perhaps it is a sign of my distinct lack of greatness that I decided to devote considerable attention to thinking about the culture of the table and its importance to a life well lived. The result is this book, which attempts to understand why this fascination with food has become so prominent in our culture. I am afraid, however, that a book about food written only for philosophers might prove to be unsavory or go to waste, and so I seek readers among the general public whose fascination with flavor takes a thoughtful turn.

Even prominent writers who take simple pleasure as their theme seem to forget their victuals. George Orwell writes:

I think that by retaining ones childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies andto return to my first instancetoads, one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable, and that by preaching the doctrine that nothing is to be admired except steel and concrete, one merely makes it a little surer that human beings will have no outlet for their surplus energy except in hatred and leader worship.

What? No shepherds pie or bangers and mash among his fond memories? I would suggest that the pleasures of life are experienced most directly when seated at a table laden with the bounty of harvest and surrounded by friends. And so I write with gratitude toward all those with whom Ive shared a table and especially those who cook with panache.

Join me for more on the philosophy of food and wine at Edible Arts (http://foodandwineaesthetics.com/).

Introduction

America Discovers Its Palate

The United States of the mid-1950s was an unlikely place to launch

a revolution in taste. In my lower-middle-class New England family, a piece of well-done beef or meat loaf, accompanied by instant mashed potatoes topped with canned tomatoes, next to a mound of canned peas, was a Saturday-only treat. Hot dogs and beans were more common. During the week, TV dinners were enthusiastically welcomed as a symbol of modern sophistication. Our nod to ethnic food included spaghetti topped with jarred tomato sauce, meatballs, and cakey parmesan powder poured from a green, cardboard cylinder. An excursion into exotica was accomplished via cans of chop sueyhunks of chicken, peppers, mushrooms, celery, and exotic bean sprouts suspended in a soy-flavored, corn starchthickened sauceserved over Uncle Bens converted rice. Chopped iceberg lettuce and tomato wedges were a salad. If fruit appeared at all, it was suspended in Jell-O. Wonder Bread was indeed wonderful. The dining tables of my better-off friends differed only in the quality of the china.

Even in high-end restaurants that served so-called Continental cuisine canned or prepared foods were too often the norm. Dishes such as crab casserole (canned crab with canned cream of mushroom soup and canned fried onions), beef stroganoff (hunks of well-done meat and noodles swimming in cream), or chicken divan (often made with precooked chicken breasts and canned soup) were considered luxurious. To be fair, the better dining establishments in New York had higher standards, but even at the famed Le Pavillon it is rumored that in the late 1950s frozen food had become the norm.

In part, the poverty of mid-twentieth-century American cuisine was the product of the deprivations of the Great Depression and World War II. But Americans have long looked askance at culinary sophistication and been wary of elitism, especially when coming from foreign influences. As recently as 2004, good taste was widely perceived as an indicator that one lacked genuine American virtue. During the presidential primary election season that year, a conservative political ad attacked Democratic presidential hopeful Howard Dean as a latte-drinking, sushi-eating, Volvo-driving left-wing freak. But there is a long history of this sort of political insult. In 1840 supporters of presidential candidate William Henry Harrison smeared incumbent Martin Van Buren as a monarchist because he drank French champagne and hired a French chef.

Throughout our history, puritanical religious leaders inveighed against taking pleasure in food. The Presbyterian minister Sylvester Graham, inventor of the graham cracker, railed against almost all foods except his beloved wheat because he thought they encouraged the sin of masturbation. And food professionals have traditionally been more interested in health concerns than enjoyment, although their prescriptions were often faddish and without scientific support. Dr. John Kellogg, the late nineteenth-century Seventh-day Adventist and inventor of corn flakes, put it bluntly: The decline of a nation commences when gourmandizing beginsthis from a scientist who advocated that patients eat nothing but grapes and chew each bite of food one hundred times.

The inevitable march of science gradually taught Americans, most of whom needed little convincing, that food should not be a source of pleasure but instead a source of fuel and nutrition. Even an authority such as Fanny Farmer, for much of the twentieth century the doyen of American home cooking, couched her recommendations in the language of science and nutrition. Historian Harvey Levenstein sums up the attitude toward food in the United States that was encouraged by the burgeoning nutrition science industry: that taste is not a true guide to what should be eaten; that one should not simply eat what one enjoys; that the important components of foods cannot be seen or tasted, but are discernible only in scientific laboratories. Elaborate meals with an assortment of ingredients were not attractive to people who wanted quick recipes with nutritional content that could easily be calculated. Undoubtedly there have always been pockets of great cooking throughout U.S. history, especially in immigrant enclaves where the flavors of home gave sustenance, but the general ethos was indifference to the pleasures of food.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.