Craft Cider Making

THIRD EDITION

Andrew Lea

This edition published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

First published in 2008 by the GoodLife Press

Andrew Lea 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 016 4

Acknowledgements

Too many people in the UK and overseas have contributed to my thinking for this book for me to acknowledge them all individually. The rise of the internet has created a worldwide craft cider community from which I am always learning. But I would especially like to thank Liz Copas for her comments on orcharding, Dick Dunn for many helpful discussions of small scale cidermaking in general, Rose Grant and Mark Powell for permission to photograph their cider houses, and Ray Blockley for supplying some of his own photographs. As for the rest of you, you know who you are!

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Just over fifty years ago a little book called Cider Making was published in the Countrymans Library (Hart Davis, 1957). It was written for the amateur by Alfred Pollard and Fred Beech, two scientists at the Long Ashton Horticultural Research Station, which had been founded in 1903 in a small village just outside Bristol. By the 1950s Long Ashton was the premier Cider Research Station in the world and had become a major centre of horticultural research. Now the site where it once stood is a housing estate.

I was privileged to work at the Research Station in its later years, from 1972 until 1985, when the Cider Section closed. Much of what is in this book I learnt from my time at Long Ashton and from colleagues such as Fred Beech, Len Burroughs, Geoff Carr, Colin Timberlake, Ray Williams, and many, many more. Now that the Long Ashton Research Station is gone for good, I would like to dedicate this little book to its memory and to the memory of the men and women who worked there and who taught me so much. I hope this book will be a worthy and useful successor to the original Cider Making of half a century ago.

I would further like to dedicate it to my family who have indulged and helped me in my hobby for so long and, in particular, to my dear wife Josephine who was my Chief Assistant Cider Maker for so many years.

Andrew Lea

INTRODUCTION

This book is aimed at anyone who wants to learn how to grow cider apples and to make good cider. You might have inherited a back garden with a couple of apple trees or several acres of derelict orchard in an idyllic rural setting. You might be scrumping apples from friends and neighbours every autumn or buying juice from someone who has a press. You might be planting a tiny suburban plot or you might be planting up an entire field. Either way, you want to learn how to make cider and this book is designed for all of you. It is aimed primarily at a UK readership but I hope will be of value to other English-speaking cider makers in North America, Australasia and elsewhere, and I have tried not to forget them.

The cider you make from this book will not be like most of what you can buy on the supermarket shelf or in a town centre bar. This book will not tell you how to make a Magners or a Strong-bow clone. It will not tell you how to make an alcopop style cider flavoured with herbs or other fruits, and it will not give you any recipes, because craft cider making is never just a matter of mixing ingredients together for a predictable result. Rather, this book aims to give you sufficient technique to be able to make cider in a way that retains the best of traditional practice, while drawing on the best modern understanding of orcharding and fermentation science. It is primarily for people working on a small scale, which could be as little as 10 litres every year up to say 10,000 litres. Larger than that and you will be verging on the industrial scale. That is not to say you cannot make good cider on a large scale you can, but with scale come additional layers of logistical and business considerations which are not dealt with in this book. However, the fundamental principles of cider making remain the same irrespective of scale.

There has never been a time quite like the present for an interest in cider in the English-speaking world. Although this is due in part to zealous marketing by the mainstream commercial operations, it is also a reflection of an increasing interest in slow-food and the connection between our food and the land on which it grows. In the temperate zones of the world the production chain between growing the fruit, making the cider and enjoying the product can be as short as a few yards. Food miles for cider can be minimal.

In this introduction we look first at the history of cider and its international distribution, and look at the definition and basic production of cider. In we take an overview of the cider making process from the fruit onwards, and in later chapters we go into each aspect more fully. Finally, there are chapters on trouble shooting and on making unfermented apple juice and cider vinegar. At the end of the book there is a list of other sources of information (since no single book has all the answers!) and suppliers of both trees and equipment.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

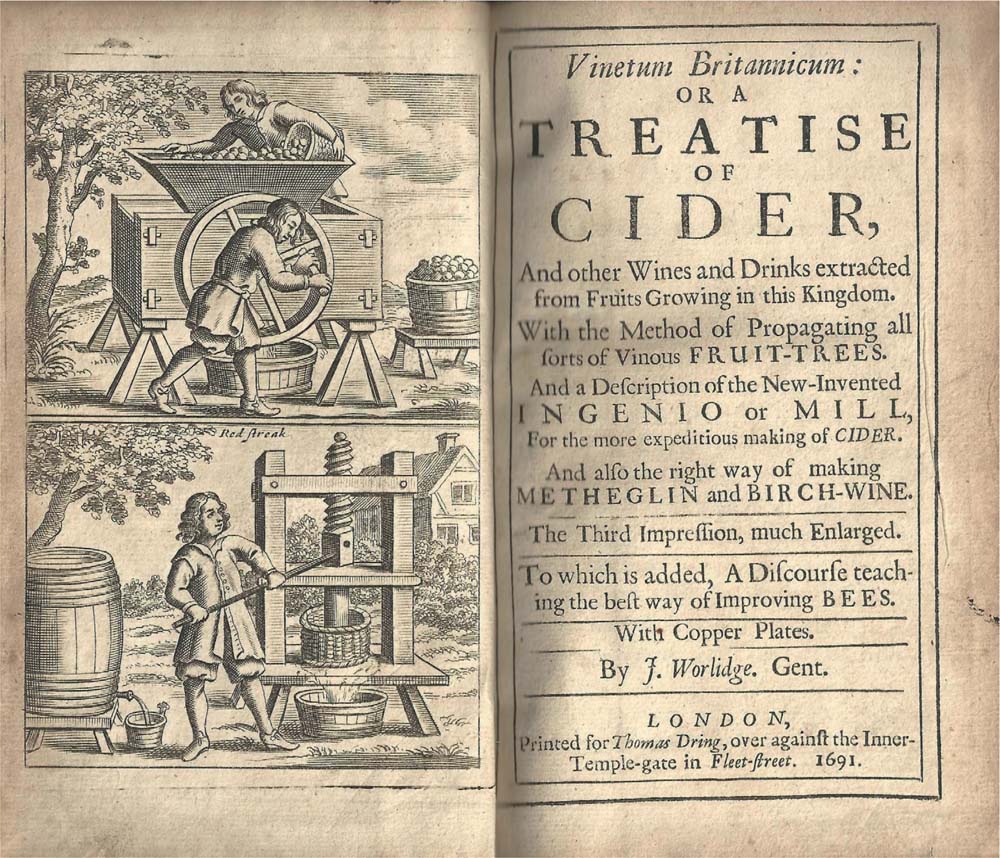

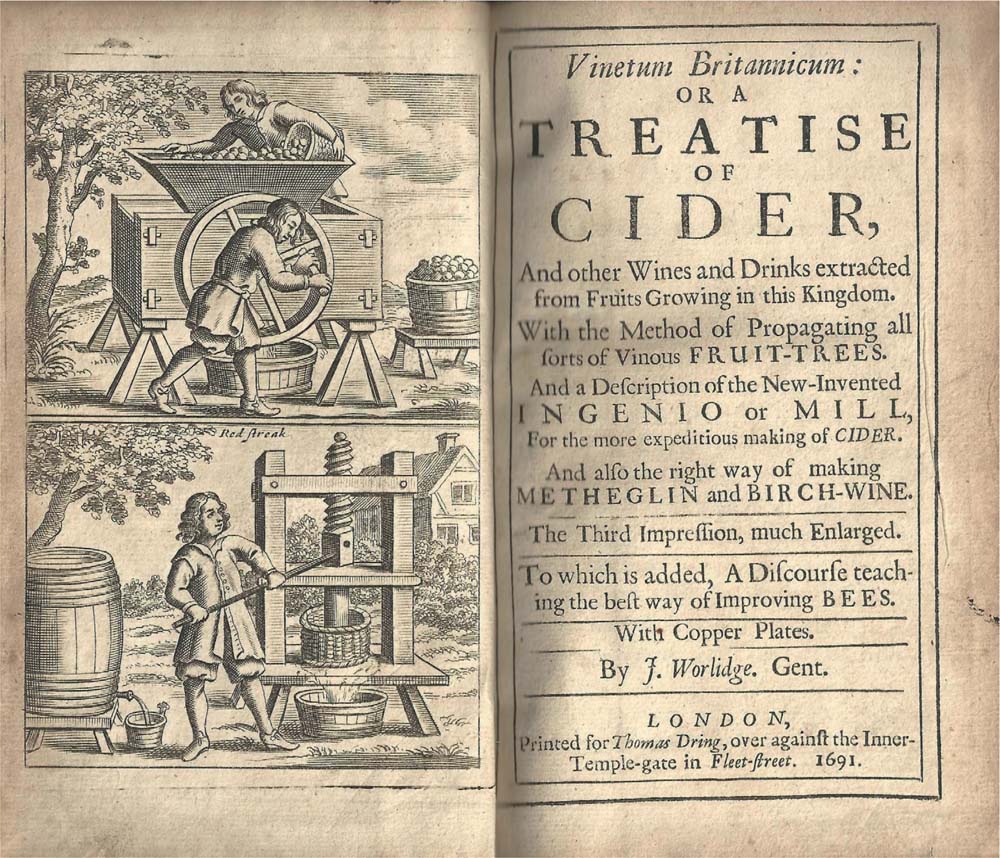

Cider has been known in Britain for around a thousand years. It seems to have been made in the Mediterranean basin around the time of Pliny (first century AD), and it became well-established in Normandy and Brittany in early medieval times (from 800 AD onwards), probably moving northwards from the Atlantic coast of Spain where cider is still made. It is not clear whether cider was made in Britain in the Anglo-Saxon period, but after the Norman Conquest it certainly seems to have taken hold here, and the first mention of established production in this country is from Norfolk in 1205. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in the stability following the English Civil War, it seemed to have reached something of a zenith with cider being compared to the best French wines and exported from the West Country to London. A number of manuals on the subject were published at this time, including John Worlidges famous Vinetum Britannicum A Treatise on Cider and Perry, which was first published in 1678. John Evelyn, the diarist, politician and arboricul-turalist, published his Pomona in 1664, which discusses fruit growing in general and cider making in particular, and included contributions from authors throughout the country. Pomona (part of his epic Sylva) went through several editions in the following century.

Title pages from the third (1691) edition of Vinetum Britannicum.

Educated and landed gentlemen such as Isaac Newton, on his family estate in Lincolnshire, are known to have been cider makers. Knowledge of its manufacture was exported to the new North American colonies (Connecticut cider is mentioned by Evelyn) and later it became a favoured drink of Thomas Jefferson, third President of the United States, who grew cider apples on his estate at Monticello, Virginia. In 1797 Thomas Andrew Knight from Herefordshire (a founder of the Royal Horticultural Society) first published his

Next page