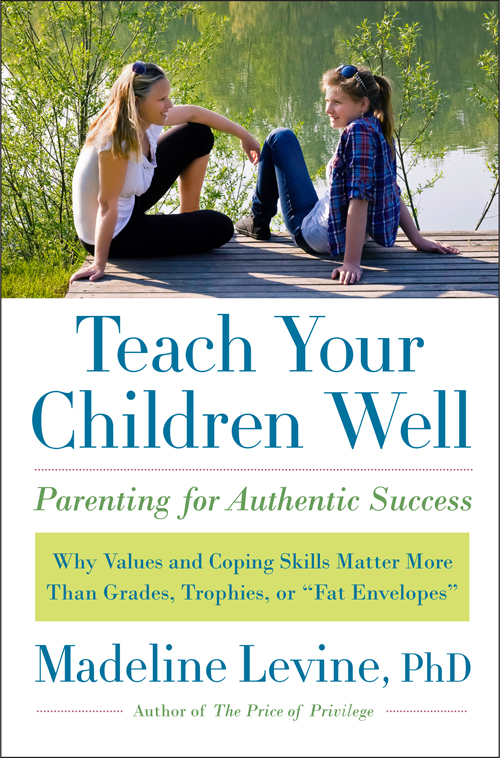

Teach Your Children Well

Parenting for Authentic Success

Madeline Levine, PhD

This book is dedicated to my mother, Edith Levine, who blessed me with unconditional love. Passed from generation to generation, her gift to me is also my childrens inheritance.

You who are on the road must have a code that you can live by.

Graham Nash

Contents

Courageous ParentingTaking the Long View

Authentic Success: Its Not About Bleeding Hearts Versus Tiger Moms

The Kids Are Not Alright (and Neither Are Their Parents)

How Did We Get into This Mess?

The School Years Are Not Just About Academics: A Primer on Child Development

The Tasks of the Elementary School Years: Ages 511

The Tasks of the Middle School Years: Ages 1114

The Tasks of the High School Years: Ages 1418

The Resilience Factor: Seven Essential Coping Skills

Teaching Our Kids to Find Solutions

Teaching Our Kids to Take Action

Walking the Talk

Defining and Living Your Family Values: A Paper and Pencil Exercise

Editing the Script: Becoming the Parents We Want to Be

Courageous ParentingTaking the Long View

W hen The Price of Privilege was published in 2006, I thought I had written a substantive, if modest, book. After all, I was reporting on the unexpectedly high rates of emotional problems documented among a relatively small group of teenagers, those from families with high levels of income and education. While I assumed my audience might be small, I knew the findings were important and counterintuitive. Privileged children, long assumed to be protected by family resources and opportunities, are experiencing depression, anxiety disorders, psychosomatic disorders, and substance abuse at higher rates than children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families who have traditionally been considered most at risk. In addition, while these privileged children often perform well on tests, they are frequently wily but superficial and indifferent learners in spite of the congratulatory e-mails and fat acceptance envelopes many of them receive from prestigious colleges.

Based on a substantial body of research, The Price of Privilege suggests that our current fashioning of success, with its singular emphasis on easily measurable achievement, is a significant contributor to the high rates of emotional problems among affluent youth. Many academically driven kids take stimulant drugs to neutralize the exhaustion of excessively long hours of homework, cheat regularly to maintain the high grades that have come to be viewed as matters of life and death, and resort to unhealthy ways of coping with overwhelming anxiety by substance abuse or self-mutilation. Just as this narrowly defined and hyperfocused system stresses many students (and their families), so does it marginalize many more who either cannot or choose not to participate in a highly standardized, pressure-cooker education. These children find the interests and talents that they do have either ignored or trivialized, and disengage from school feeling unsupported and devalued. This leaves them vulnerable to high-risk behaviors such as substance abuse and petty crime, or a hopelessness that keeps them from succeeding even on their own terms. I proposed thenas I have again in this bookthat the system responsible for these poor educational and emotional outcomes needs to be reexamined and reconfigured.

I expected to take a few months off for a book tour and related speaking engagements, and then return to the psychotherapy practice I had maintained for close to twenty-five years. Thats not what happened. Five years later I have returned to my clinical work only part-time. The Price of Privilege was reprinted seventeen times before it was released in paperback. The small group that I had anticipated would find the book relevant has morphed into an extensive and diverse collection of parents, students, business executives, clergy, educators, university administrators, and public policy experts. Apparently, many of the problems identified in The Price of Privilege stress, exhaustion, depression, anxiety, poor coping skills, an unhealthy reliance on others for support and direction, and a weak sense of selfare problems faced by large numbers of children across the country regardless of the socioeconomic status of their families. It turns out that many of these students are reporting high levels of stress whether they are trying to pass a high school exit exam or are juggling multiple AP courses.

Major governmental studies report that one in five American children and teens shows symptoms of a mental disorder and one in ten suffers from mental illness severe enough to result in significant functional impairment. The reasons for this are complex and varied. However, our children are increasingly deprived of many of the protective factors that have traditionally accompanied childhoodlimited performance pressure, unstructured play, encouragement to explore, and time to reflect. Too many of our children are simply not thriving. We know it. Yet many parents are unsure about what to do.

To begin with, we must embrace a healthier and radically different way of thinking about success. We need to harness our fears about our childrens futures and understand that the extraordinary focus on metrics that has come to define success todayhigh grades, trophies, and selective school acceptances from preschools to graduate schoolsis a partial and frequently deceptive definition. At its best, it encourages academic success for a small group of students but gives short shrift to the known factors that are necessary for success later in life. It makes the false assumption that high academic success early in life is a harbinger of competence in many spheres, including interpersonal relations and sense of self. Sometimes this is the case; often it is not. Perhaps of even greater concern, because it involves far more kids, is the fact that our limited definition of success fails to acknowledge those students whose potential contributions are not easily measurable. If we insist on a narrow and metric-based definition of success then we maddeningly consign potentially valuable contributors to our society to an undervalued and even bleak future.

The authentic success that is the subtitle of this book sees success and its development in a different light, one based not on anxiety, but on scientific research, clinical experience, and a sprinkling of common sense. This version of success knows that every child is a work in progress. It recognizes that children must have the time and energy to become truly engaged in learning, explore and develop their interests, beef up their coping skills, and craft a sense of self that feels real, enthusiastic, and capable. Authentic success certainly can include traditional measures of success such as grades and top-tier schools, but it broadens the concept to include those things that we intuitively know are critical components of a satisfying life. While we all hope our children will do well in school, we hope with even greater fervor that they will do well in life. Our job is to help them to know and appreciate themselves deeply; to approach the world with zest; to find work that is exciting and satisfying, friends and spouses who are loving and loyal; and to hold a deep belief that they have something meaningful to contribute to society. This is what it means to teach our children well.

You will often come across the words well-being in this book as one of the hoped-for outcomes for our children. There is a reason why Ive chosen well-being instead of happiness . Of course wed all like our children to be happy, but we also know (albeit reluctantly) that life will throw curveballs at our children regardless of how hard we may try to protect them. The growth (emotional, psychological, cognitive, and spiritual) needed to make ones way through life comes out of challenge, and challenge can bring disappointment, anger, and frustration. It would be foolish to want only happiness for our children. This would leave them stunted and poorly prepared for lifes inevitable difficulties. What we really want to cultivate is well-being, which includes as generous a portion of optimism as our childs nature allows and the coping skills, and therefore the resilience, that make adaptive recovery from challenge possible. As an added bonus, researchers tell us that the very characteristics that are most likely to encourage our childrens emotional well-being are the same ones that will make them successful in the classroom.