Table of Contents

ARTS & TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE: Per spec tives on Culinary History Albert Sonnenfeld, series editor

Salt: Grain of Life

Pierre Laszlo, translated by Mary Beth Mader

Culture of the Fork

Giovanni Rebora, translated by Albert Sonnenfeld

French Gastronomy: The History and Geography of a Passion

Jean-Robert Pitte, translated by Jody Gladding

Pasta: The Story of a Universal Food

Silvano Serventi and Franoise Sabban, translated by Antony Shugar

Slow Food: The Case for Taste

Carlo Petrini, translated by William McCuaig

Italian Cuisine: A Cultural History

Alberto Capatti and Massimo Montanari, translated by ine OHealy

British Food: An Extraordinary Thousand Years of History

Colin Spencer

A Revolution in Eating: How the Quest for Food Shaped America

James E. McWilliams

Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears

Madeleine Ferrires, translated by Jody Gladding

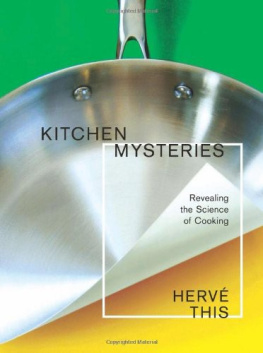

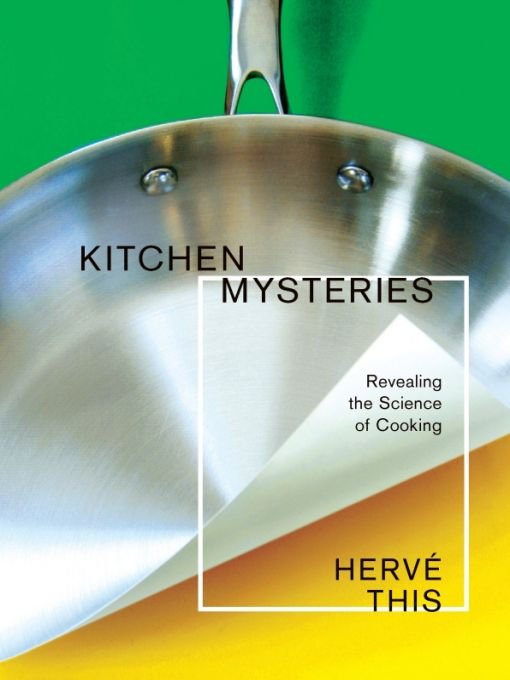

Molecular Gastronomy: Exploring the Science of Flavor

Herv This, translated by M.B. DeBevoise

Food Is Culture

Massimo Montanari, translated by Albert Sonnenfeld

Series Editors Foreword

As an ever-curious if scientifically untrained food lover and sometime home sous-chef, I have long sought to grasp the rationale that science might offer to explain the not-infrequent disasters I have produced in my unscientific and amateurish cooking. Thanks to Herv This, I discovered that I could live with the pitfalls as long as failure could become a learning experience.

What makes microwave heat so different from gas-fired ovens that it causes a tarte Tatin to go all soggy? Why did that souffl fail to rise, what diabolical chemistry caused my barnaise to liquefy? Call Herv This. He is our necessary navigator over microwaves and through formerly murky seas of culinary science.

The chefs domain is a Faustian alchemists laboratory. As Herv This demonstrates charmingly and convincingly, the mysterious transformations created there rely on predictable chemical or physiological reactions that we know how to bring about, avoid, or remedy (though we be ignorant of the scientific principles behind the phenomena). But chefs and cooks, whether amateur in the home kitchen or professional behind the stoves, anyone, in short, with more than the slightest curiosity, should want to know how things work. The incontrovertible laws of chemistry and physics are here made accessible, and their practical application demonstrated.

Why is the crust of bread tastier than the crumb? Are prosciutto and other salt- or air-cured pork products really safe? How does the chemistry of salt and air cook a ham? Why is the decomposition brought about by the enzymes in marinades a form of chemical creativity? By what chemical process does a fine red wine become corked? Under a manifesto of total accessibility, Herv This offers his reader popular [culinary] science in brief chatty chapters resembling sound bites from his famous TV shows. Overcoming whatever potential intimidation his use of basic scientific terms might arouse, Herv This writes in a style both endearing and dignified, combining science, cultural history, and humor. Kitchen Mysteries: Revealing the Science of Cooking is a worthy companion to Molecular Gastronomy, the authors first book in our series Arts and Traditions of the Table.

Molecular gastronomy: a culinary buzzword for the new millennium? In the last decades of the twentieth century controversies as to what constituted nouvelle cuisine or, later, fusion cooking inspired a veritable litany of protests from chefs denying their adhesion to such perhaps ephemeral fashions. Methinks they doth protest too much.

Today, I dont do molecular gastronomy has become a much intoned protest song for those reluctant to join in the avant-garde chorus led by Ferrn Adra, Pierre Gagnaire, Charlie Trotter, and Heston Blumenthal, to name but the most prominent innovators of a cuisine that some have called cuisine scientifique and others deconstructive. (Mind you, Heston and the others never actually did Molecular Gastronomy, because MG is science. In the beginning, some chefs did Molecular Cooking, and many others are still doing it, in spite of the fact that Heston and Ferran have now moved to culinary art instead of using the technological applications of MG. Deconstruction is another story, nothing to do with MG or Molecular Cooking.)

These great practitioners of what is in fact a panoply of variegated cuisines share a spirit of scientific inquiry. They are chefs who willy-nilly combine their art with science (caution: applied science cannot exist because if it is science, its not applied, and if it is applied, its not science but technology). No chef actually practices science, of course; they engage in a craft, because they have to produce: the kitchen is, after all, a laboratory. There, inevitably, chemical and physics experimentation is constantly under way. For example, as This emphasizes, a question ceaselessly raised and tested has to do with the ongoing importance of Maillard reactions (the action of amino acids and proteins on sugar), or what makes foods change color, to what degree does heat transform tastes or aromas? In the cooking process, a chef has to ask how to keep the primary colors of vegetables intact. What is the scientific explanation for those methods? Indeed, why do certain procedures work or inevitably fail?

Herv This examines the why behind kitchen rituals. He makes complex science easy to grasp for nonscientists and the general reader. Here we have science and history at the service of the practical in a veritable physiology of taste, one worthy of the first promulgator of gastronomic science, Brillat-Savarin!

Albert Sonnenfeld

Cooking and Science

Venial Sins, Mortal Sins

Add the cheese bchamel to the egg whites, beaten into stiff peaks, without collapsing them! Such vague instructions in a souffl recipe often make amateur cooks nervous. How to avoid collapsing those laboriously beaten egg whites? In our ignorance, we begin by using what we think is a gentlethat is, slowtechnique. The egg whites and the bchamel do not mix easily, so we stop before we have a homogeneous blend or we stir the two ingredients so long that the egg whites collapse. In both cases, the effect is the same: the souffl is ruined.

Where does the fault lie? With the cookbook that takes for granted such simple techniques, known to professionals but not sufficiently mastered by the general public? With the neophyte, who naively, even presumptuously, ventures into a discipline that is not so simple as it seems?

Difficulties like those encountered in preparing a souffl do not jeopardize our access to the realm of taste, and even the cookbooks scant instructions mark only a venial sin. With a little research, the novice will soon track down an explanation of the basic culinary techniques, and, reassured, she or he will come around to acceptingeven to wishingthat cookbooks not all repeat the same advice, which he once considered them to be lacking.