Contents

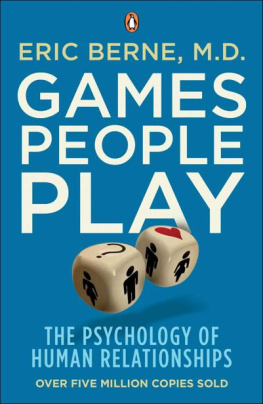

About the Book

This practical guide to Transactional Analysis is a unique approach to your problems.

Hundreds of thousands of people have found this phenomenal breakthrough in psychotherapy a turning point in their lives.

In sensible, non-technical language Thomas A Harris explains how to gain control of yourself, your relationships and your future no matter what happened in the past.

About the Author

Born in Texas, Thomas A Harris took his science degree in 1938 from the University of Arkansas Medical School. In 1942 he began his psychiatry training in Washington DC at St. Elizabeth Hospital. He was a Navy psychiatrist for several years, becoming chief of the Psychiatry Branch and leaving the service as a commander. This was followed by a teaching post back at the University of Arkansas, and then a period as a senior mental health bureaucrat. He died in Sacramento, California, in 1995.

Also by Thomas A. Harris MD, with Amy Bjork Harris

Staying OK

To Amy

my collaborator

my philosopher

my tranquillizer

my joy

my wife

Illustrations

Structural Diagram of the Personality

The Parent

The Child

Gradual Emergence of the Adult beginning at Ten Months

The Adult Gets Data from Three Sources

The Updating Function of the Adult through Reality Testing

Births of the Individual from Conception to Age Five

Prejudice

ParentParent Transaction

AdultAdult Transaction

ChildChild Transaction

ChildParent Transaction

ParentChild Transaction

ChildAdult Transaction

AdultParent Transaction

Crossed Transaction

Crossed Transaction

PatientNurse

MotherDaughter

TherapistPatient

SonFather

ManAttendant

Little GirlMother

Adolescent GirlFriend

Little GirlMother

Little BoyLittle Girl

VeronaBabbitt

HusbandWife

HusbandWife

Contamination

ParentContaminated Adult with a Blocked-Out Child

ChildContaminated Adult with a Blocked-Out Parent

The Blocked-Out, or Decommissioned, Adult

Authors Note

It is important that this book be read from front to back. Were later chapters read before the first chapters, which define the method and vocabulary of Transactional Analysis, the reader not only would miss the full significance of the later chapters but would assuredly make erroneous conclusions.

are particularly essential to the understanding of all that follows. For readers who have an irresistible back-to-front reading urge, I wish to emphasize that five words which appear throughout the book have specific meanings different from their usual meanings. They are Parent, Adult, Child, OK, and games.

Preface

IN RECENT YEARS there have been many reports of a growing impatience with psychiatry, with its seeming foreverness, its high cost, its debatable results, and its vague, esoteric terms. To many people it is like a blind man in a dark room looking for a black cat that isnt there. The magazines and mental-health associations say psychiatric treatment is a good thing, but what it is or what it accomplishes has not been made clear. Although hundreds of thousands of words about psychiatry are consumed by the public yearly, there has been little convincing data to help a person in need of treatment overcome the cartoon image of psychiatrists and their mystical couches.

Impatience has been expressed with increasing concern not only by patients and the general public but by psychiatrists as well. I am one of these psychiatrists. This book is the product of a search to find answers for people who are looking for hard facts in answer to their questions about how the mind operates, why we do what we do, and how we can stop doing what we do if we wish. The answer lies in what I feel is one of the most promising breakthroughs in psychiatry in many years. It is called Transactional Analysis. It has given hope to people who have become discouraged by the vagueness of many of the traditional types of psychotherapy. It has given a new answer to people who want to change rather than to adjust, to people who want transformation rather than conformation. It is realistic in that it confronts the patient with the fact that he is responsible for what happens in the future no matter what has happened in the past. Moreover, it is enabling persons to change, to establish self-control and self-direction, and to discover the reality of a freedom of choice.

For the development of this method we are pre-eminently indebted to Dr Eric Berne, who, in developing the concept of Transactional Analysis, has created a unified system of individual and social psychiatry that is comprehensive at the theoretical level and effective at the applied level. It has been my privilege to study with Berne for the past ten years and to share the discussions of the advanced seminar in San Francisco which he conducts.

I first became acquainted with Bernes new method of treatment through a paper that he presented at the Western Regional Meeting of the American Group Psychotherapy Association in Los Angeles in November 1957. It was entitled Transactional Analysis: A New and Effective Method of Group Therapy. I was convinced that this was not just another paper, but indeed a blueprint of the mind, which no one had constructed before, along with a precision vocabulary, which anybody could understand, to identify the parts of the blueprint. This vocabulary has made it possible for two people to talk about behaviour and know what is meant.

One difficulty with many psychoanalytic words is that they do not have the same meanings for everybody. The word ego, for instance, means many things to many people. Freud had an elaborate definition, as has nearly every psychoanalyst since his time; but these long, complicated constructions are not particularly helpful to a patient who is trying to understand why he can never hold a job, particularly if one of his problems is that he cannot read well enough to follow instructions. There is not even agreement by theoreticians as to what ego means. Vague meanings and complicated theories have inhibited more than helped the treatment process. Herman Melville observed that a man of true science uses but few hard words, and those only when none other will answer his purpose; whereas the smatterer in science thinks that by mouthing hard words he understands hard things. The vocabulary of Transactional Analysis is the precision tool of treatment because, in a language anyone can understand, it identifies things that really are, the reality of experiences that really happened in the lives of people who really existed.

Also the method, which is particularly suited to the treatment of people in groups, points to an answer to the great disparity between the need for treatment and the trained people available to do the work. During the past twenty-five years, beginning with particular intensity in the years immediately following World War II, the popularity of psychiatry would seem to have created expectancies far beyond our capacity to fulfil them. Continual outpourings of psychological literature, whether printed in psychiatric journals or the Readers Digest, have increased this expectancy yearly, but the chasm between this and cure seems to have widened. The question has always been how to get Freud off the couch and to the masses.

The challenge to psychiatry to meet this need was expressed by Mike Gorman, the Executive Director of the National Committee Against Mental Illness, in an address to the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in New York in May 1965: