Page List

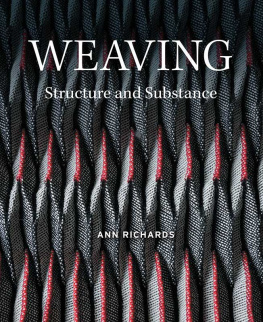

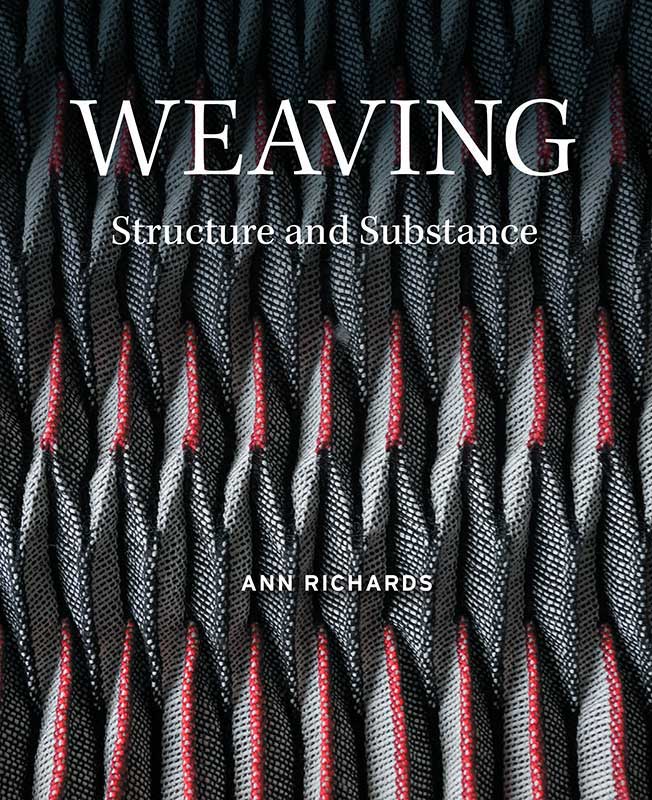

WEAVING

Structure and Substance

Self-folding origami neckpieces. Silk, steel and paper.

WEAVING

Structure and Substance

ANN RICHARDS

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

Ann Richards 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 930 3

Cover design: Peggy & Co. Design

Acknowledgements

I have to begin on a sad note because five people who have given me a great deal of help and encouragement have died since the publication of my first book. Margaret Bide accepted me as a student at West Surrey College of Art and Design, so changing the direction of my life, and she later worked hard to ensure a continuing supply of high-twist woollen merino yarn it is used for many samples in this book. Deryn OConnor and Amelia Uden, who were my stimulating tutors at college, later became good friends and were always supportive and encouraging. Amelia generously gave me a sample of her design in Russian cords, which I have included in this book. Susi Dunsmore worked for many years with the weavers of Nepal, promoting their textiles, particularly those made of allo, and holding wonderful Nettle Days that will be greatly missed by many of us. A final loss is the Japanese designer Junichi Arai, co-founder of Nuno, an important influence on my work, especially in the use of high-twist yarns. I shall continue to miss all these people who were inspirational, encouraging and full of an infectious enthusiasm for textiles.

I would like to thank the many designers and artists whose work is included here: Paulette Adam, Lotte Dalgaard, Alison Ellen, Mariana Eriksson, Berthe Forchhammer, Stacey Harvey-Brown, Denise Kovnat, Gilian Little, Noriko Matsumoto, Andreas Mller, Wendy Morris, Anna Nrgaard, Tim Parry-Williams, Geraldine St Aubyn Hubbard, Reiko Sudo, Ann Sutton, Rezia Wahid, Margrit Waldron, Angus Williams and Deirdre Wood. A special thank you to Wendy Morris for not only allowing me to use examples of her work but also reading the text and making valuable suggestions. I am also grateful to those designers who I am unable to acknowledge individually because they are unknown to me I have collected many fabrics over the years, and some of these were not attributed to a named designer. They range from simple tea towels to elegant scarves, but all are pieces that I picked up because I knew them to be useful and believed them to be beautiful.

Many thanks to Greta Bertram of the Crafts Study Centre for her help in obtaining photographs of work in the collection and to Martin Conlan and Gina Corrigan for photographs of textiles by the Miao people. I would also like to thank two archaeologists. Noortje Kramer introduced me to the remarkable Rippenkper textiles and commissioned me to attempt to replicate their effect, a fascinating process that has also fed into my own work. Johanna Banck-Burgess was responsible for the analysis of the original textile fragment that I worked from and generously allowed me to include her photograph.

The photographs have been taken by the designers and artists themselves, and by: Ole Akhj, Johanna Banck-Burgess, Alan Costall, Sanne Krogh, Hkan Lovallius, Joe Low, Loucia Manopoulou, Colin Mills, James Newell, Takao Oya, Karl Ravn, and David Westwood. Textiles and photographs not otherwise attributed are by the author.

While writing this book I have had ongoing encouragement from my friends and collaborators in the exhibition Soft Engineering: Textiles Taking Shape: Alison Ellen, Julie Hedges and Deirdre Wood. I hope we will be working together again soon.

And a final thanks to Alan for support and advice, especially with photography.

INTRODUCTION

The Interplay of Material and Structure

Although structure is all-important, the physical characteristic of an object is naturally also influenced by the material used in its making. The resulting interaction between material and structure is an absorbing study; for sometimes the material is dominant compare a silk sari with a wooden fencing panel, both interlaced in plain weave and sometimes the structure is dominant compare a felted piano hammer with a knitted Shetland shawl, both made from wool fibre.

Peter Collingwood, Textile and Weaving Structures

O f the many features characteristic of woven textiles, the aspects that probably attract the most immediate attention are colour and pattern. But underpinning these obvious features, textiles necessarily possess textural qualities and deeper tactile properties they have substance. Such aspects often receive less attention than they deserve, even though all weavers know that they are essential to the success of woven fabrics. So, although colour and pattern will feature in this book, there will be particular emphasis on the ways that tactile properties emerge from the interaction of material and structure.

Weave structure is crucial to the design of woven textiles but, being simply a plan of interlacement, it does not in itself specify what a fabric will be like. It remains an abstraction until embodied in a fabric, since fibre, yarn structure, sett, scale and finishing techniques can create so many different results. Peter Collingwood draws attention to this issue when he invites us to compare a silk sari with a wooden fencing panel, both interlaced in plain weave.

Recently, the ease of computer drafting has encouraged some designers to become absorbed in complex manipulations of structure, using programs that generate new weaves. It has even been suggested that, from the multitude of structures that result, the successful weaves could be woven as a physical record of these particular weave species. But this begs the question of how any interlacements are to be judged as successes when none have been tested as real objects.

Rather than seeing weave drafts on paper (or screen) as inherently successful, it is probably more reasonable to think of them as looking promising or having potential for particular purposes, with ultimate success or failure depending on their interplay with the material. For example, plain weave is potentially the firmest structure but nevertheless not all plain weave fabrics are firm, as this quality will vary with the texture and stiffness of the fibre, the character of the yarn and the sett. Collingwoods comparison of the silk sari and the wooden fence deliberately captures extremes of possibility in terms of fineness, stiffness and lustre of material.

More complex weaves can be thought of as having promise for particular uses on account of their characteristic styles of interlacing or length and placement of floats. But since long floats tend to allow substantial changes, through yarns sliding over one another, pulling on other threads or shrinking, the structures as weave drafts may bear little resemblance to the finished fabric. Once again, their success will depend on their interplay with the material.