Dan Saladino

EATING TO EXTINCTION

The Worlds Rarest Foods and Why We Need to Save Them

Contents

About the Author

Dan Saladino is a journalist and broadcaster who makes programmes about food for BBC Radio 4 and the World Service. His work has been recognised by the Guild of Food Writers Awards, the Fortnum and Mason Food and Drink Awards, and in America by the James Beard Foundation. Eating to Extinction was awarded the 2019 Jane Grigson Trust Award. He lives in Cheltenham but his roots are Sicilian.

To Annabel, Harry and Charlie my fellow travellers on the ark of taste

Nature has introduced great variety into the landscape, but man has displayed a passion for simplifying it.

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.

attributed to Gustav Mahler

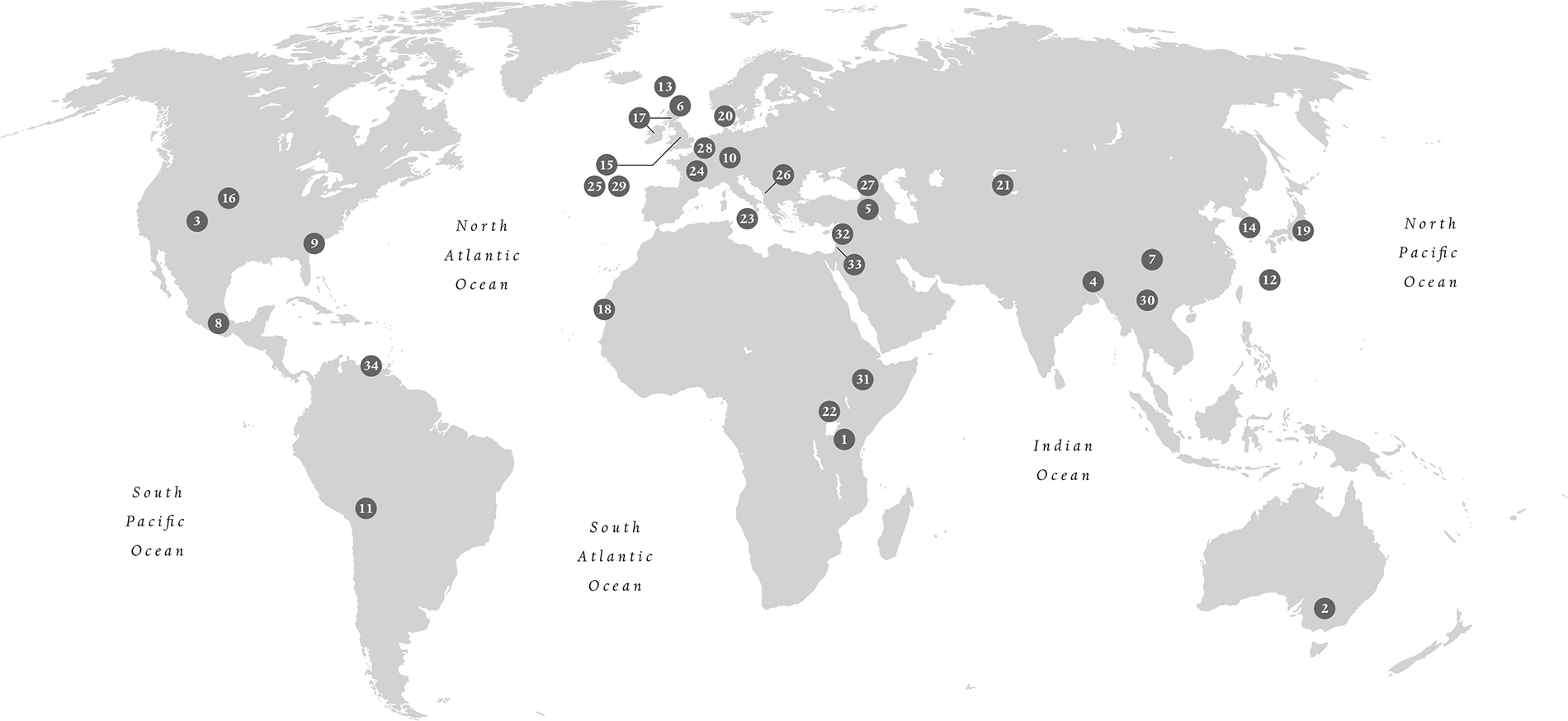

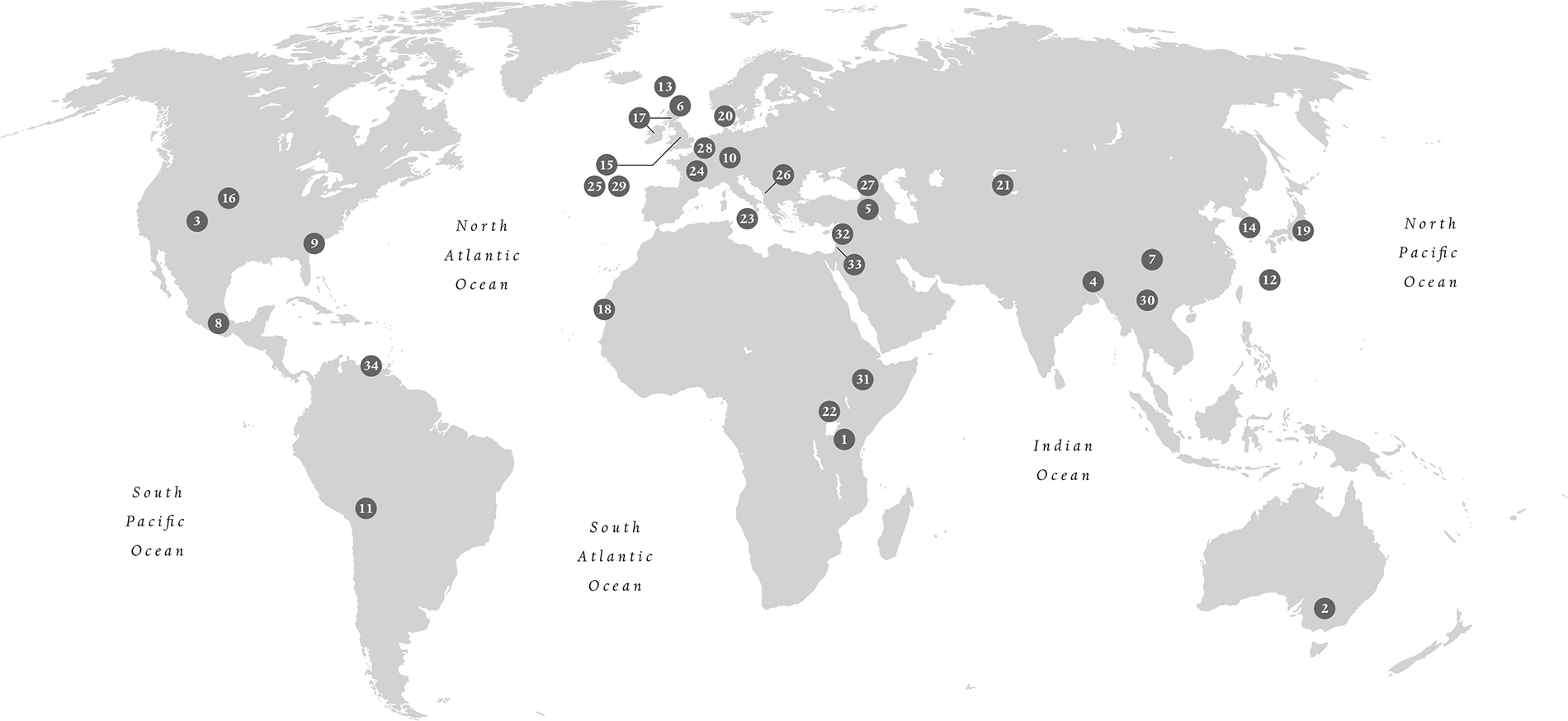

Hadza Honey (Lake Eyasi, Tanzania)

Murnong (Southern Australia)

Bear Root (Colorado, USA)

Memang Narang (Garo Hills, India)

Kavilca Wheat (Byk atma, Anatolia)

Bere Barley (Orkney, Scotland)

Red Mouth Glutinous Rice (Sichuan, China)

Olotn Maize (Oaxaca, Mexico)

Geechee Red Pea (Sapelo Island, Georgia, USA)

Alb Lentil (Swabia, Germany)

Oca (Andes, Bolivia)

O-Higu Soybean (Okinawa, Japan)

Skerpikjt (Faroe Islands)

Black Ogye Chicken (Yeonsan, South Korea)

Middle White Pig (Wye Valley, England)

Bison (Great Plains, USA)

Wild Atlantic Salmon (Ireland and Scotland)

Imraguen Butarikh (Banc DArguin, Mauritania)

Shio-Katsuo (Nishiizu, Southern Japan)

Flat Oyster (Limfjorden, Denmark)

Sievers Apple (Tian Shan, Kazakhstan)

Kayinja Banana (Uganda)

Vanilla Orange (Ribera, Sicily)

Salers (Auvergne, Central France)

Stichelton (Nottinghamshire, England)

Mishavin (Accursed Mountains, Albania)

Qvevri Wine (Georgia)

Lambic Beer (Pajottenland, Belgium)

Perry (Three Counties, England)

Ancient Forest Pu-Erh Tea (Xishuangbanna, China)

Wild Forest Coffee (Harenna, Ethiopia)

Halawet el Jibn (Homs, Syria)

Qizha Cake (Nablus, West Bank)

Criollo Cacao (Cumanacoa, Venezuela)

Introduction

In eastern Turkey, in a golden field overshadowed by grey mountains, I reached out and touched an endangered species. Its ancestors had evolved over millions of years and migrated here long ago. It had been indispensable to life in the villages across this plateau, but its time was running out. Just a few fields left, the farmer said. Extinction will come easily. This endangered species wasnt a rare bird or an elusive wild animal, it was food, a type of wheat: a less familiar character in the extinction story now playing out around the world, but one we all need to know.

The tall crop, heavy with grains, was ready to harvest. A whisper of a breeze made its surface swirl like a sea. To most of us, one field of wheat might look much like any other, but this crop was extraordinary. Kavilca (pronounced Kav-all-jah) had turned eastern Anatolian landscapes the colour of honey for four hundred generations (around 10,000 years). It was one of the worlds earliest cultivated foods, and now one of the rarest.

How could this be possible? Wheat is an ubiquitous grass that covers more farmland than any other crop, grown on every continent except Antarctica. How can a food be close to extinction and yet at the same time appear to be everywhere? The answer is that one type of wheat is different to another. Each has a unique story to tell, and many varieties are at risk, including ones with important characteristics we need to combat crop diseases or climate change. Kavilcas rarity is emblematic of the mass extinction taking place in our food. We are losing diversity in all the crops that feed the world. Yet diversity was the rule for millennia; thousands of different types of wheat have been recorded, each one distinctive in the way it looked, grew and tasted. Few of these varieties have survived into the twenty-first century. Instead, all over the world, from Punjab to Iowa, the Western Cape to East Anglia, wheat fields have been cloaked in a blanket of uniformity, and the same is happening to all our food, at a faster and faster pace.

Many aspects of our lives are becoming more homogeneous. We can shop from identical outlets, see the same brands and buy into the same fashions around the world. The same is true of our diet. In a short space of time it has become possible for us to eat the same food wherever we are, creating an edible form of uniformity. But hang on, you might say, I eat a greater variety of foods than my parents or grandparents ever did. And on one level, that is true. Whether youre in London, Los Angeles or Lima, you can eat sushi, curry, or McDonalds; bite into an avocado, banana or mango; sip a Coke, a Budweiser or a branded bottle of water and all in a single day. What were being offered appears at first to be diverse, until you realise it is the same kind of diversity that is spreading around the globe in identical fashion; what the world buys and eats is becoming more and more the same.

Consider these facts: the source of much of the worlds food seeds is mostly in the control of just four corporations; half of all the worlds cheeses are produced with bacteria or enzymes manufactured by a single company; one in four beers drunk around the world is the product of one brewer; from the USA to China, most global pork production is based around the genetics of a single breed of pig; and, perhaps most famously, although there are more than 1,500 different varieties of banana, global trade is dominated by just one, the Cavendish, a cloned fruit grown in monocultures so vast their scale can only be comprehended from the view of an aeroplane or by satellite.

This level of uniformity, from the genetics of the worlds most widely consumed crops, wheat, rice and maize, right through to the meals they become, has never been experienced before. The human diet has undergone more change in the last 150 years (roughly six generations) than in the entire previous one million years (around 40,000 generations). And in the last half a century, trade, technology and corporate power have extended these dietary changes right across the world. We are living and eating our way through one big unparalleled experiment.

For most of our evolution as a species, as hunter-gatherers and then as farmers, human diets were enormously varied. Our food was the product of a place and crops were adapted to a particular environment, shaped by the knowledge and the preferences of the people who lived there as well as the climate, soil, water and even altitude. This diversity was stored and passed on in the seeds farmers saved, in the flavours of the fruits and vegetables people grew, the breeds of animals they reared, the bread they baked, the cheeses they produced and the drinks they made.

Kavilca wheat is one of the survivors of disappearing diversity, but only just. Like all the endangered foods in this book, it has a distinctive history and a connection to a specific part of the world and its people. I came across it in a village called Byk atma, north of the part of Turkey where the very first farmers began cultivating wheat 12,000 years ago. From the time when prehistoric tribes farmed this land and on through Roman, Ottoman, Soviet and then Turkish rule, Kavilca was the most important food source here. It is only during our lifetimes that this singular grain, perfectly adapted to its environment and with a taste like no other, has become endangered and pushed to the brink of extinction. The same is true of many thousands of other crops and foods. We should all know their stories and the reasons for their decline, not just as an exercise in food history or to satisfy culinary curiosity but also, as well see, because our survival depends on it.

Next page