ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: ARCHAEOLOGY

Volume 3

TREE-RING DATING AND ARCHAEOLOGY

TREE-RING DATING AND ARCHAEOLOGY

M.G.L. BAILLIE

First published in 1982

This edition first published in 2015

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1982 M.G.L. Baillie

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-79971-4 (Set)

eISBN: 978-1-315-75194-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-138-80589-7 (Volume 3)

eISBN: 978-1-315-74868-9 (Volume 3)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this book but points out that some imperfections from the original may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Tree-Ring Dating and Archaeology

M. G. L. Baillie

1982 M.G.L. Baillie

Croom Helm Ltd, 2-10 St Johns Road, London SW11

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Baillie, M.G.L.

Tree-ring dating and archaeology (Croom Helm studies in archaeology)

1. Dendrochronology

I. Title

930.10285 CC78.3

ISBN 0-7099-0613-7

Typesetting by Elephant Productions, London SE15

Printed in Great Britain by

Redwood Burn Ltd., Trowbridge, Wiltshire.

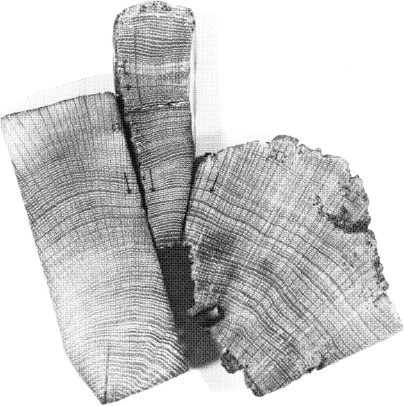

| Frontis | A rare signature pattern in samples from Trinity College, Dublin (Library), Coagh House, Co. Tyrone, and Hillsborough Fort, Co. Down |

To my father Norman Lockhart Baillie

This book is the logical extension of a doctoral thesis presented to the Queens University of Belfast in 1973. Although that research was carried out under the auspices of the Institute of Irish Studies at Queens, it was and has been since carried out within the environs of the Palaeoecology Laboratory (now Centre). My thanks must go to my colleagues who have helped in many ways over the years, in particular to Dr J.R. Pilcher for his unstinting help both in the field and in the sharing of data, and to Mr G.W. Pearson, who, with his team, has been responsible for the production of all the radiocarbon results cited below. I have received invaluable assistance from Mr B. Stocks, Mr V. Buckley and latterly Mrs E. Francis and Miss E. Halliday. I owe a considerable debt to Miss J. Hillam, who processed many of the early chronologies and who latterly has supplied numerous English chronologies for comparative purposes. I wish to thank Mr B. Hartwell for his considerable help in processing the illustrations, and Dr A. Hamlin and Mr R. Warner for permission to use . On the production side most of the text was typed by Miss J. McKay and Miss E. Bell.

However, this work could never have been carried out were it not for the totally unselfish manner in which museum curators, archaeologists, landowners and interested parties have either supplied samples or the permission necessary to remove samples and to all of them I am most grateful. The Scottish chronology owes its existence to the enthusiasm of Mr C. Tabraham in particular. I wish to acknowledge the support I have received from the Colt Fund of the Society for Medieval Archaeology, the Royal Irish Academy and in particular the Science Research Council, without whose funding most of the more recent research could not have taken place. I hope that this volume may go some small way towards justifying their expenditure. Finally, to my wife for putting up with the most unbelievable clutter during the production stages.

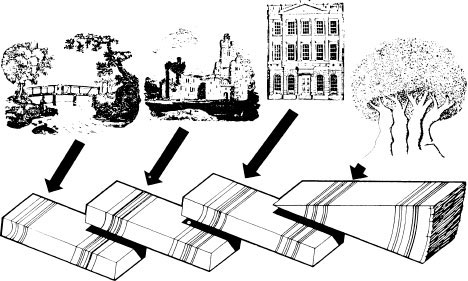

My first introduction to the concept of dendrochronological dating was in 1966 when I was given a copy of Zeuners book, Dating the Past (1958). My reaction to his section on tree-ring dating, where he described the early work of Douglass, was surprise at the elegance and simplicity of the method. In essence he was describing the basic principle of dendrochronology as shown in Figure 1. That is, overlapping of the ring patterns of successively older timbers to build a master sequence or chronology and the subsequent dating of wood samples by comparison of their individual patterns with the established chronology. The essential quality of Douglass archaeological dating was that, in the era before radiocarbon dating, he was establishing exact ages for buildings of the prehistoric period. It is unimportant that for Douglass the prehistoric era was any time before AD 1492. In Ireland, for example, written history notionally runs back to a few centuries after Christ. However, the quality of that evidence and the paucity of references to the objects and structures with which archaeology is concerned make archaeological chronology in Ireland before AD 1100 little better than that in the south-western United States.

Curiously, in reading of the American work at that time I was not moved to ask why the method was not being applied in the British Isles. I think now that the reason must have lain in the exotic quality of the dating and the assumption that it could only work in distant desert lands. Thus I little suspected that I would later spend many years following a very similar course to that of Douglass half a century before.

. Schematic representation of the construction of a chronology by the overlapping of successively older ring patterns.

Source: Courtesy Ulster Museum.

The reason behind my involvement with tree-rings stemmed from a scientific background coupled with an interest in archaeology. Inevitably the possibility of working with a method which might allow the establishment of precise dates for archaeological material from periods where dating was, at best, somewhat vague (and at worst virtually non-existent) had considerable attraction. In particular in Ireland and throughout the British Isles there was a great need for some chronological backbone in the early historic period, the first millennium AD. While it may seem that it is the prehistoric period which is in greater need of dating precision, in fact this is not so. In prehistory (in the British Isles that is broadly the BC era) by definition there is nothing absolute with which to compare precise dates. It is in the protohistoric and historic periods that dendrochronology allows comparison between the dates of archaeological structures and written documentation to the greatest effect. So in the first analysis the most useful chronologies will cover the last two millennia.