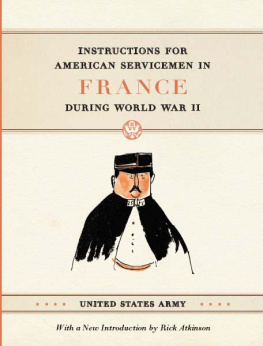

Pages 172 of this book are a facsimile of a pocket guide prepared by the Army Information Branch of the Army Service Forces, United States Army, in 1944 .

This work is reproduced with the kind assistance of Mary Summerfield and of the Special Collections Research Center at Regenstein Library, the University of Chicago.

Rick Atkinson is the author of An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 19421943, and The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 19431944, volumes one and two of The Liberation Trilogy, a narrative history of the American role in the European theater during World War II.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

Foreword 2008 by Rick Atkinson.

All rights reserved. Published 2008

No copyright is claimed for the text of the Short Guide to France (pages 172) published by the War and Navy Departments of the United States Army in 1944 .

Printed in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08

1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-84172-4 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-84172-3 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-84175-5 (electronic)

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pocket guide to France

Instructions to American servicemen in France during World War II / with a new foreword by Rick Atkinson.

p. cm.

Originally published: A pocket guide to France / Army Information Branch of the Army Service Forces, United States Army. 1944.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-84172-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-84172-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. FranceDescription and travel.

2. National characteristics, French.

3. World War, 19391945France. I. United States. Army Service Forces. Information and Education Division. II. Title.

DC28.P63 2008

914.404816dc22

2007043865

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

FOREWORD

Rick Atkinson

Amid the mountains of war materiel accumulating in southern England in the spring of 1944 were crates of a slender, highly classified book intended to give Allied soldiers a sense of the country they would soon overrun. One million copies of what was then titled A Pocket Guide to France, and has been retitled Instructions for American Servicemen in France during World War II for this edition, had been requested by the War Department in a top secret message, making the little volume among the most ambitious publishing ventures of World War II. As explained in a cable from Washington to the headquarters of General Dwight D. Eisenhower in London, the book was intended to give a general idea of the country concerned, to serve as a guide to behavior in relation to the civil population, and to contain a suitable, concise vocabulary.

The A.B.C. Booklets, as they were originally called, had a curious history. What is being done in War Department to provide guides to countries of Europe? a cable from London to Washington asked on December 17, 1943. Many inquiries received. The reply came a day later, from Lieutenant General Brehon B. Somervell, the Armys chief logistician, to Lieutenant General John C. H. Lee, who served as Eisenhowers supply chief:

Short guides series now in preparation. Includes manuscripts for Norway, Yugoslavia, France, Greece, Albania, Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark, Rumania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Germany. Written by civilian and OSS [Office of Strategic Services, predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency] experts, cleared by War Department agencies. Order of preparation determined priority. Classified secret until distributed

The highest priority was assigned to the French guide, for it was on the beaches of Normandy that the Allied high command had agreed to launch Operation Overlord, the invasion of western Europe that would result in the final defeat of Nazi Germany. Initial printings would be made in England, to avoid security breaches in shipping so many books overseas, and then distributed to the troops aboard their invasion ships.

By mid-January 1944, Eisenhowers staff had begun to chafe at delays in receiving the manuscripts from which the guide would be printed. When can arrival be expected of first copies? a message to Washington asked on January 13. Another query followed a week later: information requested when first finished manuscripts may be expected. The reply from the War Department on January 20 advised, manuscripts of short guides to France, Holland, Norway, Belgium, Luxembourgdispatched 17 January by courier pouch to chief of psychological warfare branch [in] your theater for clearance.

By early February, something clearly had gone awry. Regarding guides to countries of Europe, Lee cabled Somervell on February 4. What were article numbers given them by Army Courier Service in Foreign Mail Room Washington for pouch dispatched 17th Jan 44?Copies of guides not received to date. Many inquiries regarding them.

The snafu came clear in Somervells reply from Washington the following day. These manuscripts were dispatched originally 15 January and were returned here unopened because erroneously addressed to Major General Robert H. McClure instead of correctly addressed to Brigadier General Robert A. McClure. The well-traveled documents were again dispatched, and placed in the hands of the proper McClure on February 9. Printing began soon after, and stacks of books joined the fifty thousand vehicles, four hundred and fifty thousand tons of ammunition, and countless sticks of chewing gumto combat seasicknessaccumulated for Overlord.

Like the vehicles and the ammo, the guide did its part to win the war. Soldiers were proselytized on the need to liberate France and the worthiness of the French to be liberated. Neither assertion was necessarily obvious to most GIs. France in 1940 had made a separate peace with the invading Germans, and the first enemies fought by American troops across the Atlantic were French soldiers and sailors in Morocco and Algeria during the North African invasion of November 1942. That was to be forgiven, if not quite forgotten, since many Frenchmen had since thrown in their lot with the Allied cause. We are friends of the French and they are friends of ours, the guide instructs. The Germans are our enemies and we are theirs.

If sometimes extraneousdid Private Smith really need to know that one hectoliter equals twenty-two gallons?and occasionally patronizing of both GIs and FrenchmenNormandy looks rather like Ohiothe guide evinces generosity, respect, and affection for suffering France. The liberators were told, accurately in this instance, to expect a big welcome from the French. Americans are popular in France. Extracting France from German occupation had a flinty, practical purpose: the enemy will be deprived of coal, steel, manpower, machinery, food, bases, seacoast and a long list of other essentials which have enabled him to carry on the war at the expense of the French.

Certainly the guide had its quirks, including a penchant for stereotype. The French were said to be mentally quick, economical, realistic, and individualists. They are good talkers and magnificent cooks, but they have little curiosity. Residents of Marseilles are southern, turbulent and hot-headed. In an assertion that would seem especially suspect in a nation that championed the shrinking work week, the guide asserted, respect for work is a profound principle in France.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.