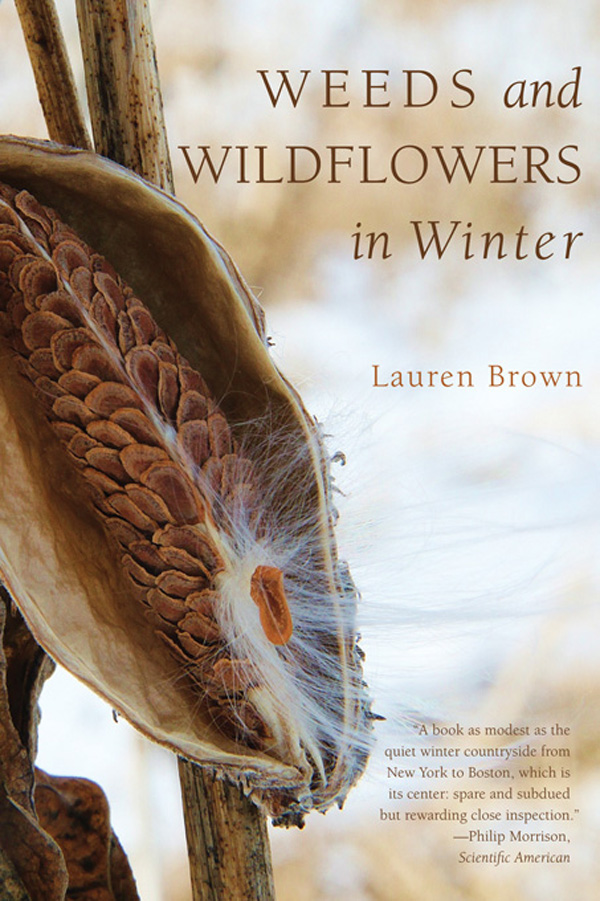

WEEDS AND

WILDFLOWERS

IN WINTER

WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED BY

Lauren Brown

To all my friends

CONTENTS

I owe more than I can ever realize to Tom Siccama, a former professor at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. As a teacher always willing to give time to his students, Tom helped me identify many of these plants and showed me how to go about identifying them on my own. He was genuinely interested in this project, and his interest encouraged me and, most important, got me moving. Dr. Alfred E. Schuyler, of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, who taught me plant taxonomy in the first place, critically read the entire manuscript and corrected many mistakes. I am grateful to him for setting aside so much time on so little notice. Dr. John Mickel, of the New York Botanical Garden, offered helpful suggestions on the section on ferns.

At W. W. Norton & Company, Ned Arnold originally accepted the manuscript, and I owe thanks to Bob Pyle for steering me in his direction. The book was guided through the production process by Sherry Huber, whose efficiency, competence, and pleasantness were admirable, and critical in getting the book out. The designer was Marjorie Flock, who was always a pleasure to work with.

Aside from professional help, several people fall into the moral support category: Lloyd Irland, and my parents, Ralph and Elizabeth Mills Brown. Lloyd and my mother not only read and criticized but also always encouraged me. Liz Mikols, my friend, also read the manuscript and made many valuable comments. Kristine Ashwood saved the day when I needed a typist, and she served as much more, running errands and dropping everything to work on this project. Gary Wolfe generously gave his time as a guinea pig to test out the key. Many others helped me in this regard: my aunt Sarah McCulloch, Anne Bittker, several patient friends, and many students who had no choice, but who were cheerful about it anyway.

L AUREN B ROWN

Guilford, Connecticut

In New England, almost half the year is winter. The flowers and the greenery that brought us so much pleasure from April to October are gone, and people who enjoy looking at and identifying plants put their books away. However, the plants have by no means disappeared and it is still perfectly possible to identify them. Many books have been published already which teach people how to identify trees and shrubs in winter by the characteristics of their twigs and bark. But what about the rest of the plantsthe weeds and wildflowers?

Any plant that is not a tree or a shrub is herbaceousits living parts die to the ground by the end of each growing season. Herbaceous plants include what we commonly refer to as wildflowers, weeds, grasses, ferns, and mosses. Herbaceous plants have three kinds of life cycles. If the entire plantabove and underground partsdies at the end of each season, it is called an annual; if the underground parts survive and send up new shoots in the spring, it is a perennial. If the plant has a two-year life cycle, it is a biennial. In its first year a biennial produces only a rosette of basal leavesalmost stalkless leaves close to the ground. The second year, the plant sends up a flowering shoot, and then it dies. The garden carrot, which is the same species as the wildflower Queen Annes Lace, is a biennial.

Although they may be dead, many herbaceous plants do not disappear over the winter. They remain as dead, woody tissue, various shades of brown or gray, sometimes with fruits, sometimes just as stalks; and many of them are spectacularly beautiful. Thoreau wrote about these dried plants in his journal:

When the ground was partially bare of snow, and a few warm days had dried its surface somewhat, it was pleasant to compare the first tender signs of the infant year just peeping forth with the stately beauty of the withered vegetation which had withstood the winterlife-everlasting, goldenrods, pinweeds, and graceful wild grasses, more obvious and interesting frequently than in summer even, as if their beauty was not ripe till then, even cotton-grass, cattails, mulleins, johns-wort, hardback, meadowsweet, and other strong-stemmed plants, those unexhausted granaries which entertain the earliest birdsdecent weeds at least, which widowed nature wears.

Many of them bear little resemblance to the plants that they were in the summer, for some of the most inconspicuous summer plants leave the most beautiful remains, and vice versa. The wild yam (Dioscorea villosa ), for instance, blends in completely with its surroundings in summer, but in winter anyone with an eye for form cannot help but notice its amazing three-sided hearts twining in among other dead plants. On the other hand, many of our more common wildflowersviolets, dandelions, buttercups, cloversdisappear completely by the end of the summer.

You have probably picked these dried things and brought them into your house for decoration. You may even have gone to a gift store and paid outrageous prices for something that you could have picked along the edge of the New Jersey Turnpike. If you ever tried to identify any of these plants, you probably found your books useless. By keeping your eyes open, and waiting six months, you might notice what comes up in the spring in the spot where you saw a certain dried stalk in the fall. But it is hard to keep your eyes open all of the time. This book is designed to identify common dried herbaceous plants as they are found in the winter. It is written for the lay person. We assume that you are interested in plants, but that you know little about botany.

You should know a little bit about how plants are classified. They are classified at many different levels, but we will mainly be concerned with three groupings: the family, the genus, and the species.

Family A knowledge of plant families is extraordinarily useful. Plants are placed in various families on the basis of the characteristics of their flowers. Of course, you cannot see the flowers in the winter, but there are many other family characteristics, such as leaf arrangement, flower arrangement, or kind of fruit, that carry over into the winter. Most plant books are organized by family, so if you know what family a plant is in, identification is a lot easier.

This book is organized for the most part by family. When there is only one representative of a family, or when two winter plants of the same family have nothing in common, the plants have been put in a Miscellaneous section at the end. But it should not take you long to recognize some of the more common families, and then you will have a much easier time identifying your winter plants.

Genus and Species A genus (the plural is genera ) is a smaller grouping of plants within a family. Goldenrod, Solidago, is a genus. A particular kind of Goldenrod, such as Grass-leaved Goldenrod, is the species Solidago graminifolia. Once we have referred to a certain species of Solidago in a passage, we can abbreviate it the next time as S. graminifolia; if we want to refer to another species in the same genus, we can call it S. rugosa, or S. nemoralis. You will see some plants in this book identified by the genus name followed by spp. for example, Solidago spp. This designation indicates that we have an unidentified species of the genus Solidago.

Do not be afraid of Latin names. They eliminate much confusion, because a specific plant has only one Latin name, which applies to that plant only. Common names have developed informally and they vary widely, so that misunderstandings often arise. For instance, Lepidium campestre, a member of the Mustard family, in three widely used wild-flower guides is called Field Cress, Cow Cress, and Field Peppergrass. Some of its close relatives are Spring Cress, Winter Cress, Early Winter Cress, Rock Cress, Peppergrass, and Field Pennycress. It becomes hard to remember which Cress is which. Lepidium campestre, however, is always Lepidium campestre. The Latin names may seem meaningless, but if you know any Latin derivatives, you will see that many of them are very descriptive. I have tried to explain the Latin names wherever they are helpful.

Next page