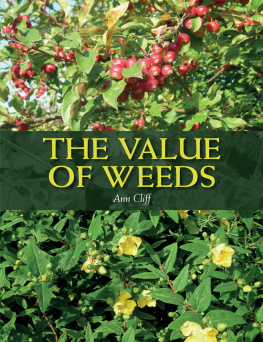

THE VALUE

OF WEEDS

THE VALUE

OF WEEDS

Ann Cliff

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2017 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2017

Ann Cliff 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 279 3

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks are due to the many people who have given me help and encouragement in putting this book together.

Peter and Irene Foster of Lime Tree Farm, my brother and sister-in-law, have generously shared their knowledge and experience of converting the farm for wildlife conservation. Im grateful for their hospitality over many years, including cups of Irenes hawthorn berry tea. In spite of the fact that much of my time is now spent in Australia, they keep me in touch with Lime Tree and the natural world in Yorkshire. (Irene made the weed frittata featured in the recipe chapter and it was excellent.)

Jill Askham and Martin Varley have been with me on many field trips and have provided company, equipment, transport and refreshments. On cross-country walks we have tracked down weeds, fallen into bogs, taken photographs of lovely wild flowers, and enjoyed the varied countryside of the Yorkshire Dales.

John Earnshaw read the Weeds for Health chapter of the book and offered valuable insights into his profession: he is a scientific herbalist who likes to collect his own plant material.

Norman Bush gave me help with the chapter on dyeing, and kindly modelled his jacket creation, dyed with lichen. Norman is a craft teacher who delights in foraging for weeds. He also lent me books from his eclectic collection.

Tony and Wendy Robins provided the photograph of hand hoeing, and explained how they control weeds on their organic farm.

I am grateful to the staff at Artison craft workshop at Masham, North Yorkshire, and especially tutor Jess Wilkinson, for insights into the craft of willow weaving and her creative use of weeds.

Michael Harrison kindly supplied the photograph of duckweed.

Thanks as always to my husband Neville, for his support.

Ann Cliff

INTRODUCTION

Can you tolerate weeds? It may be an acquired skill: we have been fighting them for thousands of years and it may not be easy to give up. In conventional thinking weeds are the enemy, and sometimes this is true. However, many weeds are beneficial, even essential, and thats what this book is about.

Weeds are rascals, sometimes villains, cheeky survivors, enjoying life wherever they can find a roothold in the earth. They are often a neglected resource in gardens and on farms or wherever they grow. Weeds are not always the enemy of cultivation. In spite of everything we throw at them they forgive us and thrive, contributing biomass, healing the scars we inflict on the earth, and giving us food and medicine. Some of them light up our lives with beauty.

Whats the definition of a weed? The word comes from old English weod meaning grass or herb, but it has come to mean a plant we despise.

Dont be ashamed of your weeds or not all of them. Only a few are a real menace, a matter for elimination, while many weeds have value. Weed is a negative label, bestowed upon a plant because its been rejected by our culture. A plants status can vary over time and location; some of our despised weeds were once valued vegetables, and some are still cultivated in other parts of the world.

A weed may be growing in the wrong place, or it meets with disapproval because of its frightening fecundity. Were scared it will take over and this can happen. Our food plants depend on us to help them grow in spite of weed competition, and conventional food production demands the elimination of weeds.

Some weeds are so beautiful that we forgive them for appearing unexpectedly. Honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum), pushing through a hedge with long trailing vines, drenches the evening air with fragrance. This is Shakespeares luscious woodbine, a favourite hedge plant, the creamy flowers tinged with red and deepening to orange as they fade away. The two lips of the flowers form a tube that is much visited by long-tongued moths at night from May to August.

Honeysuckle is a wild climber.

Honeysuckle is essential to the survival of a spectacular gliding butterfly, the white admiral, in forested areas. Black with white bands on the upper side of the wings, this butterfly lays its eggs on honeysuckle leaves, which provide food for its caterpillars. As we will see, many weeds are important to our wildlife.

Ground elder.

Of course there are nuisance weeds. Many of us battle with ground elder (Aegopodium podagraria), of which more later. This weed is invasive and very hard to eliminate. Any plant not native to a natural environment can be an undesirable influence because it can change the balance of an ecosystem. Ground elder, or gout weed, has been moved round the world as an ornamental plant, or as a vegetable or medicine. It is a nuisance, but its also good to eat.

Another such invader is Indian or Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera), a plant introduced to Britain in 1839 for its looks. It grows rampant along some of our river systems, changing the ecology of the river banks. Many other plants were brought to Britain by plant hunters looking for new fashions in gardening. Originally much admired, some have become weeds.

In the case of weeds introduced from other countries, the natural controls that keep these plants in check in their native lands are often not present in the UK, which is one reason why they have become a problem. DEFRAs list of the worst invasive plants demonstrates this (see the for some of them).

However, its not all bad news. In some circles there is a fresh mindset about the plants that surround us, as we realize that many weeds have virtues but its hard to give up our orderly ways. Its easy to spray out of existence any plants that grow uninvited in the wrong place, especially when they threaten to compete with our carefully nurtured cultivated plants. Weeds are untidy. Trying to keep our gardens, farms and window boxes as neat as those in glossy magazines, we also have to compete with friends, neighbours and television gurus. Our standards in Britain seem to have been set by the beautiful gardens of stately homes, tended by armies of gardeners in the past.

We like to spend time outdoors in manicured spaces, but to save work there is so much paving and gravel that few plants survive and weeds, of course, are banned.

So what happens when we get rid of sprays and think about weeds in a more positive way? For a start, we save money and cut down our reliance on chemicals. We stop releasing potentially harmful substances into the environment, and avoid the risk of contaminating our fresh garden produce. We help bees, among many beneficial insects including other pollinators, to survive. We start to notice some fascinating inhabitants of the plant world.

Next page