For my son, Orlando

Contents

- FIRST MOVEMENT:

Sognando - SECOND MOVEMENT:

Volante - THIRD MOVEMENT:

Pianoforte

Guide

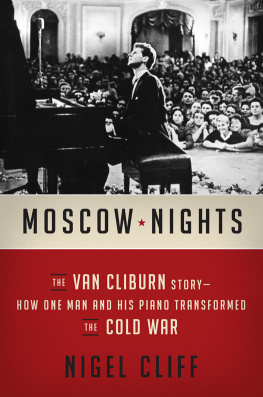

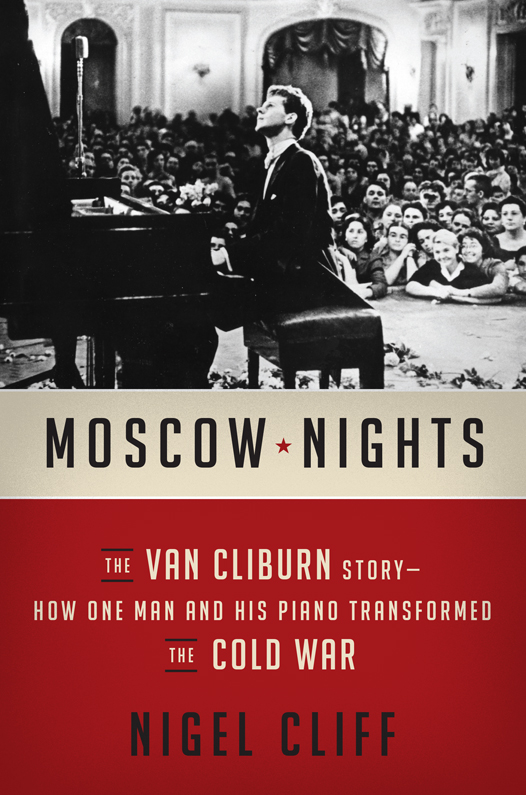

ON MAY 28, 1958, ticker tape snowed from the sky above Broadway, darkening an already gray New York City day and flurrying around rapturous, flag-waving crowds. High school bands marched, Fire Department colors trooped, and at the center of it all was a young American perched on the back of an open-top Continental, grinning in disbelief and crossing his hands over his heart. He was as tall, thin, and blond as Charles Lindbergh, but he was not a record-setting aviator. Nor was he an Olympic athlete or a world statesman or a victor in war. The cause of the commotion was a twenty-three-year-old classical pianist from a small town in Texas who had recently taken part in a music competition.

Whats goin on here? a stalled taxi driver yelled to a cop. A parade? Fer the piano player?

The cabbie had a point. No musician had ever been honored like this. No American pianist had been front-page news, let alone a household name. But the confetti was whirling, the batons were twirling, and on a damp morning a hundred thousand New Yorkers were cheering and climbing on cars and screaming and dashing up for a kiss. In the summer of 1958, Van Cliburn was not only the most famous musician in America. He was just about the most famous person in Americaand barring the president, quite possibly the most famous American in the world.

Things got stranger. At a time when the United States and the Soviet Union were bitter enemies in a perilous Cold War, the Russians had gone mad for him before Americans had. Two months earlier he had arrived in Moscow, a gangly, wide-eyed kid on his first overseas trip, to try his luck in the First International Tchaikovsky Competition. Such was the desperate state of world affairs that even musical talent counted as ammunition in the battle of beliefs, and everyone understood that the Soviets had cranked open the gates only to prove that their virtuosos were the best. Yet for once in the tightly plotted Cold War, the authors had to tear up the script, for the real story of the Tchaikovsky Competition was beyond the imagination of the most ingenious propagandist. The moment the young American with the shock of flaxen curls sat before the piano, a powerful new weapon exploded across the Soviet Union. That weapon was love: one mans love for music, which ignited an impassioned love affair between him and an entire nation.

It came at a critical time. Five months earlier the Soviet Union had sensationally beaten the United States into space. Even now, shiny metal sputniks were whizzing above American roofs, which suddenly seemed puny shields against a newly menacing sky. In this hallucinatory and panicked age, Van Cliburn gained the trappings of a rock star: sold-out stadiums, platinum albums, screaming groupies, and vindictive rivals. The implausible extent of his fame was captured when the Elvis Presley Fan Club of Chicago switched allegiance and changed its name to the Van Cliburn Fan Club. He brought millions of people to classical music, yet more than a pianist, he was a talisman: a locus of hopes that through his music he could heal a troubled world.

He hoped so, too, but the moment of youthful glory that made him also trapped him. An innocent required to play a global role, a gregarious charmer obsessed with privacy, a model of piety with a rebellious streak, a driven man who could be hopelessly dysfunctional, a patriot who loved Communist Russia, a man-child who was old when young and young when old, a lover of aristocracy proud of his humble Texas roots, a modest man who was not above embellishing his own legendVan was both what he seemed and not what he seemed. As the Cold War lurched from one crisis to another, he played on, returning emotionally to Moscow, courted by presidents and Politburo members, watched by the FBI and KGB, and closely guarding a secret that could have destroyed him overnight. In those days when clashing ideologies counted no cost in human lives too high, he stood impotently by while several of his fellow competitors met with tragic fates. While superpower relations plumbed new depths, he disappeared to become Americas most famous recluse, his one-man musical peace mission seemingly a busted flush. Yet, just when all looked lost, the legend of Van Cliburn would rise again to answer the call of history.

Based on numerous interviews and newly revealed evidence from Russian and American archives, this book tells the full story of Van Cliburn and the Tchaikovsky Competition for the first time. That story is inextricably linked to the Cold War, which turned a music competition into an event of global significance, and its main players, especially Nikita Khrushchev and the U.S. presidents he tangled with: Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. It also takes us through the remarkable careers of the piano concertos by Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, written at the height of Romanticism, that supplied the unlikely sound track to three decades of global conflict.

If Vans tale resonates particularly strongly today, that may be because events overtook the writing of this book. A window on a recent but seemingly vanished world now opens onto terrain that looks all too familiar. While we contemplate talk of a new Cold War, it can be illuminating to recall that Russia and America have had a love-hate relationship for a long while. Both nations became world powers at the same time, as multiethnic states with one foot in Europe with its old-world refinement and the other in their vast rude hinterlands. Both were ideologically extreme nations with utopian identities: America the shining city on a hill; Russia the third Rome and the chalice of true faith, be it Orthodox or Communist. Yet whereas America promoted happiness through freedom, Russia sought stability through autocracy. And while Americas exemplary heroes were businessmen and industrialists, Russias were artists who peered into the human soul with an unmatched intensity.

The conflict between these young-old nations defined the second half of the twentieth century not only because of their military might but also because of the stark choice thrown up by their distinctly different views of human nature. Yet deep down there was common ground, waiting to be rediscovered. It was unexpected that it happened through music, but in a way it was a return to form. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries there was no place that loved Russian music more than Americanot even Russia itself.

A SHORT STORY ABOUT TCHAIKOVSKY...

BY 1874, Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky had been professor of theory and harmony at the Moscow Conservatory for each of the eight long years since it opened its doors. The grand title belied a desultory salary (fifty rubles a month), and the thirty-four-year-old musician supplemented his income by working as a roving critic. Both jobs took him away from composing, which had yet to earn him more than lukewarm praise. To Russians his music was too Western, to Europeans too unmannered; one Viennese critic contemptuously likened it to the brutish, grim jollity of a Russian church festival where we see nothing but common, ravaged faces, hear rough oaths, and smell cheap liquor. So when Tchaikovsky decided to write his first piano concerto that year, he set out to meld Western and Russian musical practices into a new style that would win universal approval and finally let him quit his tiresome post. In bold strokes he conceived a big, virtuosic work brimming with catchy folk themes: a melody he heard performed by blind beggars at a market and others taken from Russian and Ukrainian folk songs and a French chansonette, Il faut samuser, danser et rire. By late December the concerto was sketched out, and he inscribed a dedication to Nikolai Rubinstein, the founder and director of the conservatory and a fine pianist in his own right. Tchaikovsky hoped Rubinstein would agree to give the premiere, and on Christmas Eve, before heading out to a party, Rubinstein asked the reticent composer to play the concerto through.