Contents

ALSO BY STUART ISACOFF

A Natural History of the Piano: The Instrument, the Music, the Musiciansfrom Mozart to Modern Jazz and Everything in Between

Temperament: How Music Became a Battleground for the Great Minds of Western Civilization

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2017 by Stuart Isacoff

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Isacoff, Stuart, author.

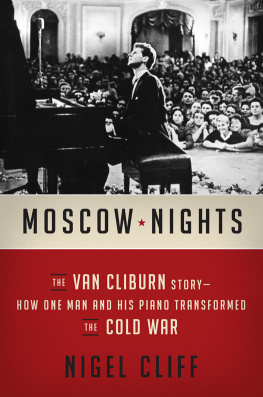

Title: When the world stopped to listen : Van Cliburns Cold War triumph and its aftermath / by Stuart Isacoff.

Description: New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: lccn 2016032873 | ISBN 9780385352185 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780451494030 (eBook)

Subjects: lcsh: Cliburn, Van, 19342013. | PianistsUnited StatesBiography. | International Tchaikovsky Competition (1st : 1958 : Moscow, Russia) | MusicCompetitionsRussia (Federation)Moscow.

Classification: lcc ml417.c67 i83 2017 | ddc 786.2092 [b] dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016032873

Ebook ISBN9780385352192

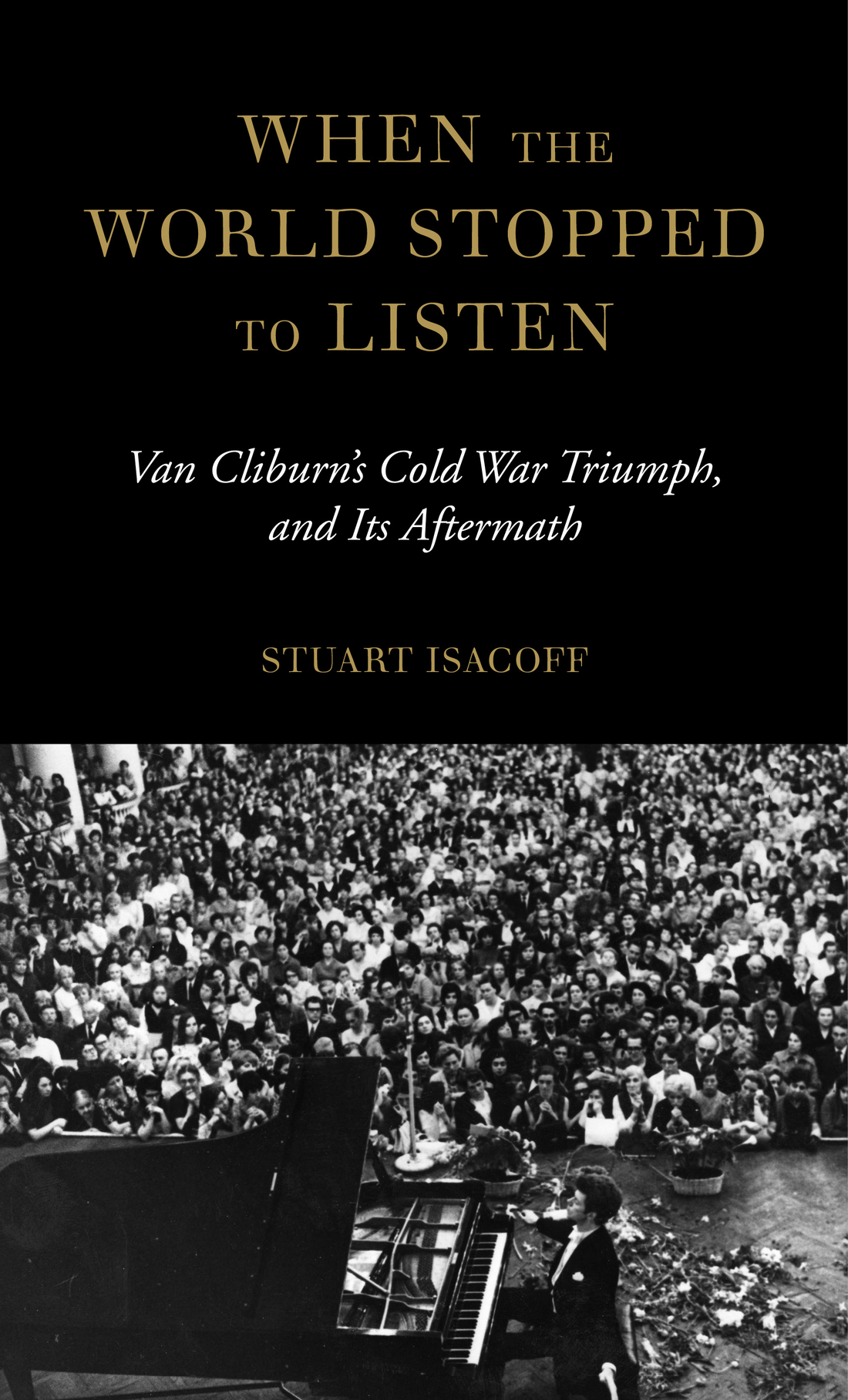

Cover image: Van Cliburn during the Tchaikovsky Competition, Moscow, April 1958. Courtesy of the Van Cliburn Foundation.

Cover design by Peter Mendelsund

First Edition

v4.1

a

In memory of my mother, Hannah

The changing wisdom of successive generations discards ideas, questions facts, demolishes theories. But the artist appeals to that part of our being which is not dependent on wisdom; to that in us which is a gift and not an acquisitionand, therefore, more permanently enduring. He speaks to our capacity for delight and wonder, to the sense of mystery surrounding our lives; to our sense of pity, and beauty, and pain; to the latent feeling of fellowship with all creationand to the subtle but invincible conviction of solidarity that knits together the loneliness of innumerable hearts, to the solidarity in dreams, in joy, in sorrow, in aspirations, in illusions, in hope, in fear, which binds men to each other, which binds together all humanitythe dead to the living and the living to the unborn.

JOSEPH CONRAD

Contents

PROLOGUE

Crowds in the Streets

T HE CROWDS GREW DAILY in front of the Moscow Conservatory of Music: workmen in their fur hats; matriarchs draped in black coats and scarves; teenage girls clutching bundles of flowers and shivering in the crisp air. A haze of chilled breath covered those who gathered, like fine dust. Clouds hovered overhead, lending a bleak cast to the setting. It was April, when the patches of ice on Moscows streets usually give way to the spring sun, as tender blades rise up from beneath the grounds frozen surface. In 1958, though, the ghost of winter lingered on. And people still continued to congregate.

They clustered around the monument of Tchaikovsky at the perimeter of the schoola restructured eighteenth-century manor house, once occupied by royaltyand spilled out into the snow-covered courtyard. As they reached a wall of militiamen blocking the entrance, their unsynchronized parade congealed into a serried mass before falling into disarray.

In a city where people often queued up even without knowing what they might findfish? bananas? concert tickets?long lines were a way of life. Writer Igor Efimov invented a character who secretly loved these assemblages: She felt peaceful in them, as if contained in a safe shell composed of the people in front of and behind her. Most Muscovites simply resigned themselves to the situation. In this crowd, though, people were fired up.

They were there hopefully to see the talk of the town: a long-legged young Texan whose soaring pianism had for days been enthralling audiences at the first-ever Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition, a high-culture version of the World Cup pitting musical talents from around the globe against one another. The contest had been designed to bolster Soviet pride by anointing a hometown winner. Yet all attention was now focused on the uncanny American whose musical talent stunned the judges and drove mobs of ordinary citizens into a frenzy.

The buzz about him began in the Conservatorys Great Hall during the contests opening round, and soon floated through the city like a vapor. As newspaper editors and broadcasters fanned the excitement, tickets became as rare as the Romanov crown jewels. Van Cliburn, from Kilgore, Texas, was all the rage. Workers with little education began to stalk certain streets hoping for a glimpse of him. When pianist Lev Vlassenko, the Soviet Unions top contender in the competitionand the Kremlins presumptive winnertook a taxi to the conservatory, the driver asked him, And how is the tall one doing?

It was a stunning turn of events. Tension between the United States and the Soviet Union had been steadily rising since the launch in 1957 of the first Sputnik space satellite. By the time of the Tchaikovsky Competition, the West was collectively holding its breath out of fear that bombs would soon be falling from the skies; American children regularly practiced diving under their desks in school in preparation for the coming disaster.

With such pervasive antipathy between the nations, no one could have predicted that by the end of the first two series of eliminations an American would be poised to reach the top rung in this Soviet contest. In a culture where nearly everything was based on political calculation, Vans advance toward a possible victory was big news. Yet, to nearly everyone who heard him, it seemed inevitable.

He was six foot four and capped by bushy blond hair (the American ambassadors wife dubbed him Brillo Top). His face had an Irish lilt, with its finely sculpted jaw and cheekbones; thin, sensual lips; and cornflower-blue eyes. And he was oh, so thin! When seated at the piano he looked like a peapod with great Jack the Giant Killer hands, said one of his managers, Schuyler Chapin. Critic Winthrop Sargeant described the pianists fingers as a bunch of asparagus. Neither image sounded especially lovely, though each framed him as a force of nature.

Nevertheless, remembered Max Frankel, then in Moscow as a correspondent for The New York Times, young Russian girls were swooning. Women of a certain age wanted to adopt him. Their daughters had other designs.

His admirers in the concert hall and those who heard him over the radio or saw him on television were hooked almost from the moment the twenty-three-year-old first appeared on the stage. But it wasnt the music alone that drew them. His Southern charm was as thick as gravy on fresh biscuits as he greeted his new fans with the prim decorousness of a proper East Texas gentleman, unfailingly gracious at every turn. The Russian public had embraced virtuosos before, but Van was a different sort. He showed none of the brooding intensity of Sviatoslav Richter, or the demonic sparks of Vladimir Horowitz; the ground and the walls didnt shake when he performed, as they had seemed to for Anton Rubinstein. He simply played like an angel. Muscovites surrendered their hearts to him.