WEEDS

Reaktions Botanical series is the first of its kind, integrating horticultural and botanical writing with a broader account of the cultural and social impact of trees, plants and flowers.

Published

Apple Marcia Reiss

Bamboo Susanne Lucas

Cannabis Chris Duvall

Geranium Kasia Boddy

Grasses Stephen A. Harris

Lily Marcia Reiss

Oak Peter Young

Pine Laura Mason

Willow Alison Syme

Weeds Nina Edwards

Yew Fred Hageneder

WEEDS

Nina Edwards

REAKTION BOOKS

For J.M.B.

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2015

Copyright Nina Edwards 2015

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgments and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780234847

Contents

Weeds grow everywhere.

Introduction

W eeds are everywhere. We may try to bend nature to our will, but on the peripheries of herbicide-drenched fields, squeezed between paving slabs and seeded in the crevices of city walls, these often disregarded plants grow and prosper. They are the tough underclass of the plant world, bullying their way into drainage systems, poisoning meadowland, stealing essential nutrients and taking a stranglehold on plants we deem legitimate. Yet in those far-flung places where wilderness remains we often do not bother to consider weeds at all. And they require our attention. Weeds exist only in relation to ourselves.

Weed is a word that conceals inherent contradictions. In German it is something less than other plants, the un-herb, the Unkraut, echoing the Nazi term for a Jew, Unmensch, an un-person. In French and Spanish it is a bad herb, a herb gone wrong, mauvaise herbe, mala hierba. The modern Italian erbaccia is also pejorative, suggesting something ugly and useless. In Latin viriditas is also less derogatory simply a green thing. The English word weed is derived from the Old Saxon wiod, related to a fern, a wild and prolific plant. Though the derivation of weeds as a word for clothing is otherwise, from the Old Saxon wad, the term nonetheless suggests a sense of plentiful fabric, as in womens clothing, or dark, dishevelled, wild disregard, as in widows mourning weeds. Waedless was a term for naked and waed-brc for breeches. Edmund Spenser, in his The Faerie Queene, has A goodly Ladie clad in hunters weed (Book 2, canto III.xxi).

The common names for weeds are robust, no-nonsense and plainly descriptive: pigweed, goutweed, snout, nosebleed. Turn to the Glossary and you will see that English terms for weed species are often Anglo-Saxon, and there is no beating about the bush with piss-a-bed, bridewort, fleabane or madwomans milk. The Latin double-barrelled system has gravitas but lacks a certain attack. In its everyday name the function of or dread surrounding a particular plant is often laid bare.

For followers of Zen, weeds are treasures; for Christians they may act as a reminder of almighty design. In an introduction to Taoist philosophy, removing weeds to allow crops to flourish signifies the need to cleanse the mind, for unless they are removed, concentration and wisdom will not grow.

When the novelist Deborah Moggachs mother began to pull up garden plants and leave the weeds behind, it was a sign that she was beginning to suffer from dementia. Weeds can be a gauge of human behaviour, and in Shakespeare they suggest personal disorder, particularly in the sonnets, and political upheaval when weeds such as darnel, hemlock, and rank fumitory are allowed to flourish in Henry V (Act V, Scene 2). If weeds are wild plants, plants out of our control, then those that inhabited the earth before our coming might all be so called.

Weeds, then, are despised, voracious plant life if found in the garden border, but in the wild, beyond our perception, when we cannot see or do not care to know what damage they may be doing, it is a matter of live and let live. The perceptive gardener may think twice before rooting up all weeds in their path, noticing what they reveal about soil fertility, whether it is acid or alkaline, and perhaps fearing that patch where nothing ever grows. The ecologist may reckon that the balance of plant life in a particular habitat has been threatened by the success of one species over others more worthy of existence, particularly if it is new to an area, proscribed as an alien invader thriving at the expense of other so-called indigenous plants that have more right to exist there. And for a plant to be alien, it has to have been introduced by human activity, either intentionally or unintentionally, and so one might argue that weeds are our fault; yet we blame the weeds.

Camille Pissarro, Woman Working in a Garden, c. 1900, watercolour over black chalk.

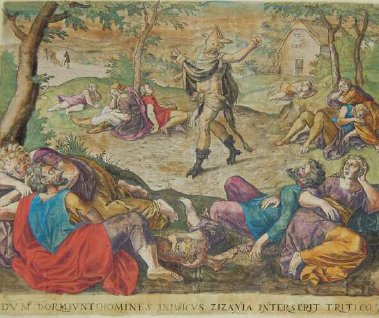

Satan sowing darnel. Print by Pieter Jalhea Furnius after Gerard Groenning, 1585.

The idea of weeds challenges a romantic notion of there being a natural balance in vegetable and animal society, where plants live together harmoniously in a mutually beneficial set of relationships. If weeds create a persistent problem, they are easily thought of as criminal recidivists, carrying all the fear and loathing of their human counterparts, threatening what should be gentle, cooperative nature. Cooperative with our interests, that is. They crop up unexpectedly, and proliferate like sexually promiscuous immigrants, vying for available living space and greedily taking more than their share of available sun, rain, shelter and food. Many weeds reproduce asexually, of course, but the point here is that their powers of reproduction can seem a parallel with licentious human behaviour.

Take camfhur grass as an example, a tropical shrub of the sunflower family whose rapid growth and easy reproduction by seed and root renders animal forage toxic. Each plant can produce 80,000 to 90,000 seeds. The plant is said to have first escaped from North America in the nineteenth century, not only to India from botanical gardens in Pakistan but also to African rainforests via its accidental addition to forestry seed. Although it was introduced to control cogon grass in pastureland in the Ivory Coast, in Sri Lanka it has infested coconut plantations and, like so many plants that remain relatively innocuous in more temperate regions, it has become a virulent weed across Australia.