Publisher: Amy Marson

Creative Director: Gailen Runge

Editors: Karla Menaugh and Liz Aneloski

Technical Editor: Debbie Rodgers

Cover/Book Designer: Casey Dukes

Production Coordinators: Tim Manibusan and Joe Edge

Production Editors: Jennifer Warren and Nicole Rolandelli

Illustrator: Aliza Shalit

Photo Assistant: Carly Jean Marin

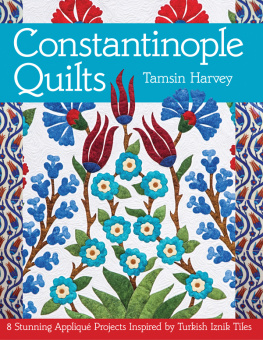

Tile photography by Tamsin Harvey and instructional photography by Diane Pedersen of C&T Publishing, unless otherwise noted

Published by C&T Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 1456, Lafayette, CA 94549

Dedication

To Angela, who made this Ottoman garden bloom and come to life

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

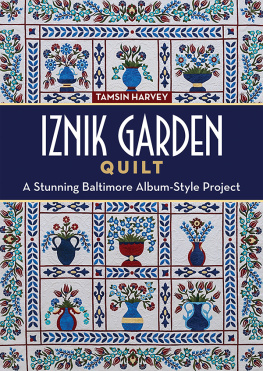

Iznik (also written as znik) pottery and ceramics find their origins in the Ottoman Empire, dating back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. During this time, the empire was one of the most powerful states in the world. While conquering various regions and expanding their empire, the Ottoman sultans created a new cultural identity for their homeland, absorbing and adopting many traditions and art forms from conquered regions. They brought artists from these regions back to the capital, Constantinople, to create beautiful handcrafted items that would decorate their palaces. It was during this period that Iznik pottery and ceramics boomed.

These ceramics were inspired by Chinese porcelain, which was highly prized by the Ottoman sultans but expensive. Iznik was ideal for ceramic production due to its nearby deposits of potters clay and quartz and its forests that would fuel the kilns. Located in Western Anatolia, in the province of Bursa (historically known as Nicaea), Iznik was near the capital, which also allowed for ease of delivery.

Iznik had been creating cheap and rather ordinary pottery since before the fifteenth century. To put the town in a position where it could create luxury items worthy of the new court, the Ottoman court began sponsoring workshop factories to educate the ceramic makers. As the artists started to develop their skills and knowledge, they developed a new form of ceramic decoration called underglaze painting, transforming Iznik into a town known for superb technical quality and artistry.

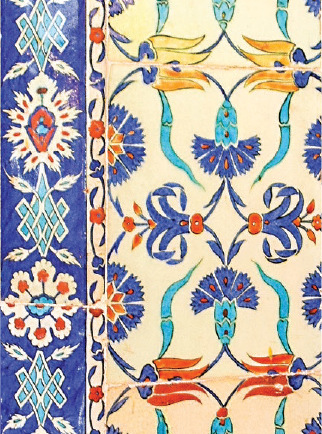

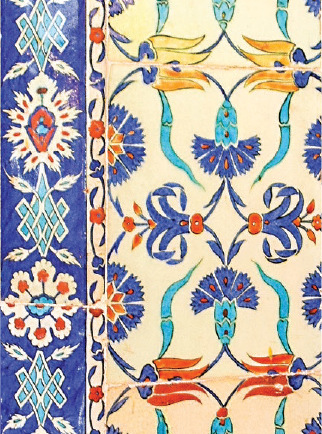

Images of Iznik tiles located in the Rstem Pasha Mosque

Soon artists started experimenting with the colors and the designs painted on tiles. The early examples of Iznik wares consisted mostly of a single colorcobalt blueand the designs were simple. During the 1530s, the artists began to add pale purple, red, green, and turquoise. Designs such as floral motifs emerged, which included tulips, carnations, peonies, roses, and hyacinths. Iznik wares, now prized for their quality and uniqueness, were being exported over much of the Middle East and Europe.

During the reign of Sleyman the Magnificent (15201566), demand for Iznik wares increased. Sleyman was one of the longest reigning sultans of the Ottoman Empire. He not only expanded the empire by conquering other regions but also brought great wealth to it, moving the empire into the golden age of its cultural development. During this time, Mimar Sinan (Architect Sinan) created some of the well-known buildings that are still standing today, many decorated with large quantities of Iznik tiles.

Iznik tiles can still be found in many palaces, mosques, and tombs. The Rstem Pasha Mosque (Istanbul, Turkey) contains the most spectacular arrangement of Iznik tiles found in any mosque.

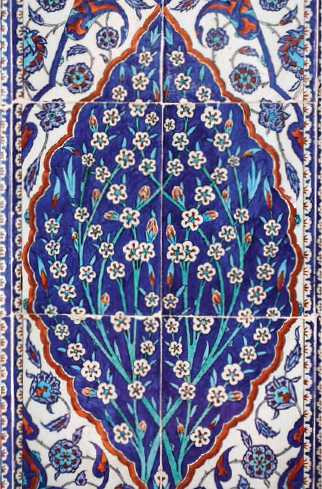

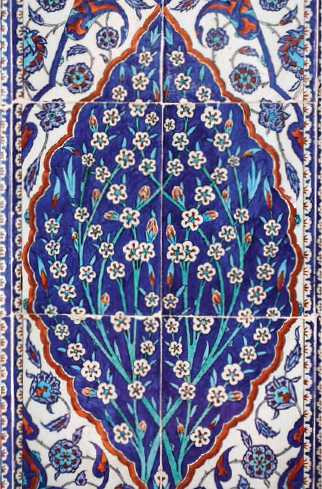

The Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Istanbul, Turkey) contains more than 20,000 handmade ceramic tiles featuring designs of flowers, fruits, and cypressesincluding 50 different tulip designs. The tile colors have given this mosque its more commonly used name, the Blue Mosque.

Some of the beautiful tile designs found in the Sultan Ahmed Mosque

A panel in the Topkap Palace

A vase in an Iznik tile design, found in the tombs at the Hagia Sophia Museum

The Topkap Palace (Istanbul, Turkey) was the primary residence of the Ottoman sultans and their courts from 1465 to 1858. Many rooms, walls, and pavilions within the palace and its grounds feature a selection of tiles, mosaics, and large panels.

Toward the end of the sixteenth century, the quality of Iznik pottery began to decline. The decrease in the number of new imperial buildings, the imposition of fixed prices, and restrictions on tile production put in place by the sultans lead to the decline. Artists started to move away; slowly knowledge and traditions were lost.

We are fortunate that Iznik tiles and ceramics have stood the test of time. They can be viewed in many historic buildings in both the capital of Istanbul and other regions. The ceramics can be found in numerous museums throughout the world, especially in many European museums, such as the Louvre (Paris, France) and the British Museum (London, England). Modern-day reproductions of Iznik tiles are still very popular, keeping the tradition alive.

Iznik Garden pays homage to the women of the Ottoman Empire. The imperial harem was an important part of the empire that existed between 1299 and 1923 and was made up of the sultans wives, servants, female relatives, and concubines. The mother of the sultanreferred to as the valide sultanand the sultans wives could hold great power and influence over the sultans, affecting the interests of, and the decisions made by, the Ottoman Empire.

The majority of the sultans mothers were from foreign lands. Brought to the harems at a young age, some of these girls would find themselves presented to the sultan as a gifta prize of war, or even a slave who was sold to the imperial harem. They would be educated, and only the most suitable would ever see the sultan. The others would become the servants necessary for the daily functioning of the harem. Producing heirs was important to the Ottoman Empire, and having a son could elevate a womans status within the harem. If her son was successful in becoming the next sultan, a slave woman from a simple background could influence her son and hold great power as the head of the harem.

Next page

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION