Table of Contents

Guide

Gunther Martin

Euripides, Ion

TEXTE UND KOMMENTARE

Eine altertumswissenschaftliche Reihe

Herausgegeben von

Michael Dewar, Adolf Khnken,

Karla Pollmann, Ruth Scodel

Band 58

De Gruyter

ISBN 978-3-11-052255-6

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-052359-1

e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-052341-6

ISSN 0563-3087

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress.

Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der

Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet

ber http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar.

2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

www. degruyter.com

Preface

Things do not look the same when distant and when seen from close up. Ions words (5856) capture in different ways the experience of this commentator. At the outset, the task seemed straightforward: to answer every question that might be asked. It soon turned out to be unfeasible, and even presumptuous. Interpretations of the text that originally seemed compelling came to seem evasive, as the details of the text pushed themselves to the fore. Initially I had believed that the constitution of the text was a job practically finished by earlier generations and that its discussion would not be of great profit to either myself or the reader; and even though my approach to textual matters has remained a conservative one (or so at least do I see it), a closer look revealed that a certain revisiting of textual questions was warranted.

Ion has inspired important readings from scholars with a great variety of approaches, most notably using structuralist ideas, dynamic of the text, the artfulness of composition, and the dramatic effect it produces. In this way will it be possible to appreciate a vital part of the enjoyment the play can bring to its audience.

This commentary has been long in the making. During this period, I have accumulated personal and scholarly debts to a great number of people. I have profited from and made the best I could of much advice and (mostly fair and constructive) criticism. Sections were read by Chris Collard, James Diggle, Patrick Finglass, Gregory Hutchinson, Tobias Reinhardt, Katharina Roettig (KR in the commentary), Alan Sommerstein (AS), and Walter Stockert (WS). David Kovacs in addition offered excellent general advice and let me see parts of his forthcoming commentary on Troades . Help on specific problems was offered by Herbert Bannert, Esther Eidinow, Solmeng Hirschi, Maxim Polyakov, Stefan Rebenich, Scott Scullion, and Nick Stylianou. For permission to cite the theses by John Wa and the late James Irvine I thank the author and Allan Irvine respectively.

My most profound and very special thanks go to Arnd Kerkhecker (AK), who read and commented on the entire first draft with his usual good sense and superb feel for texts. He also generously supported its acceptance by the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Bern as my Habilitationsschrift in October 2013. He was seconded by Gerlinde Huber-Rebenich, Richard King, Thomas Spth, and Martin Hose, who also offered rich comments on the entire draft.

I am grateful to the editors of Texte und Kommentare in particular to Ruth Scodel for accepting this book into the series, to Emanuele Rovati for his help in preparing the manuscript and the index, to David van Schoor for polishing the English, and to Katharina Legutke for seeing the volume through the press. The Fondation Hardt at Vandoeuvres and the departments at Nottingham, Bern, and Zrich have hosted me very kindly during various fellowships, and without the generous support of the Swiss National Science Foundation I would very likely have been unable to bring this project to fruition.

The first inspiration to this book, much good advice, encouragement when dearly needed, and not least a of happy memories came from the British branch of my family. The motivation to keep going and the ability to do so was given me by the Swiss side.

Weingarten, Mnnedorf

January 2017

Introduction

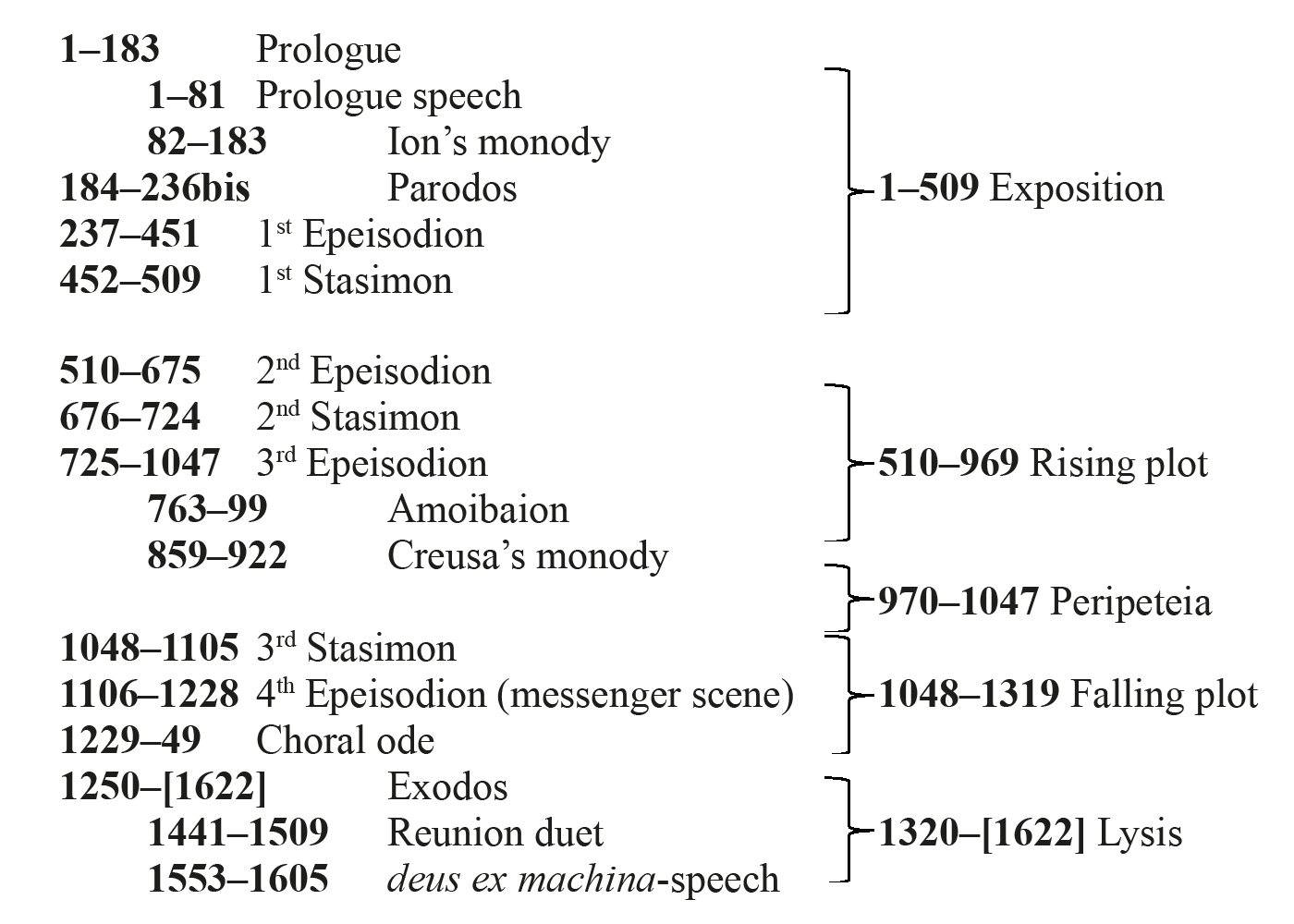

1) Structure

Greek tragedies follow a relatively strict and simple sequence of building blocks, but this formal structure often does not converge with the dynamic of a play. In Ion , too, turning points can be located in the middle of epeisodia, or acts. Hence the following table maps the formal description against the pyramidal model of dramatic action, which by and large captures the course of events even of a play so rich in turns.

Exposition: The length of the expository section (as opposed to the Prologue as formal part of the play) is striking, amounting to almost one third of the play. The pre-history seems neatly covered by Hermes prologue speech, but then Euripides introduces the characters at great length: Ions song shows him as the dedicated, humble, and pure temple slave in perfect harmony with his duties and his environment, but also reveals how he is vexed by the opprobrium of his low social standing and not knowing his mother.

The chorus enter (Parodos) and make clear from the very first lines their Athenianness. The 1 st Epeisodion has still not set in motion the action but introduces Creusa. She engages in a long conversation with Ion ( 237400 ), through which the audience are prepared for some of her later conduct: she too suffers, as she has not overcome the loss of her son. Then Xuthus arrives, bringing the oracular response from Trophonius that he and Creusa would not leave Delphi without a child.

At the end of the exposition we have two very different addresses to gods: Ion reproaches Apollo for the amorous antics he has just learned about, while the chorus in the 1 st Stasimon pray to Athena for intercession with Apollo when he gives his response to Xuthus.

Rising Action: The plays conflict is set up by the oracle that declares Ion to be Xuthus son. Ion reluctantly accepts that announcement and Xuthus emotional embrace but has reservations about leaving for Athens. These, however, are quickly brushed aside by Xuthus. He names his (hitherto nameless) son and instructs him to arrange a party both to secretly celebrate their reunion for Ion will be declared a companion, their supposed relationship concealed and to take farewell of the people of Delphi.

The chorus are startled by the development, compassionate with their mistress, and outraged by Xuthus unsolidary behaviour and the prospect of some nobody from outside coming to their city (2 nd Stasimon). They harbour doubts about the oracle as reported, but these are not pursued in the subsequent course of events.

Creusa returns (3 rd Epeisodion), eager to learn about the response, with her fathers slightly absurd old tutor. The atmosphere swiftly changes when the chorus give a pointed paraphrase of the oracle, telling her that Xuthus has been given a son but that she is to remain childless. The Old Man reconstructs a scenario that makes Xuthus pursue a plan to plant his illegitimate son in Creusas house. Creusa, fixated on her private grief, her future loneliness, and Apollos unfair lack of grace, launches into a passionate (sung) accusation against the god the emotional climax of the play. The low point of utter despair is reached when Creusa tells the Old Man about her lost son.

![Euripides - Classic Greek Drama: 10 Plays by Euripides in a Single File [NOOK Book]](/uploads/posts/book/43473/thumbs/euripides-classic-greek-drama-10-plays-by.jpg)