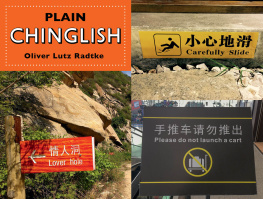

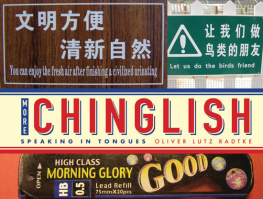

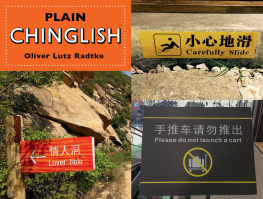

Oliver Lutz Radtke - Chinglish : found in translation

Here you can read online Oliver Lutz Radtke - Chinglish : found in translation full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Layton, UT, publisher: Gibbs Smith Publisher, genre: Children. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Chinglish : found in translation

- Author:

- Publisher:Gibbs Smith Publisher

- Genre:

- City:Layton, UT

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Chinglish : found in translation: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Chinglish : found in translation" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Chinglish : found in translation — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Chinglish : found in translation" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Chinglish

Digital Edition v1.0

Text 2007 Oliver Lutz Radtke

Photographs 2007 as noted

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Gibbs Smith, Publisher

PO Box 667

Layton, UT 84041

Orders: 1.800.835.4993

www.gibbs-smith.com

ISBN: 978-1-4236-0784-7

Engrish.comthe Japlish counterpart by Steve Caires

Hanzismatter.comChinese character tattoos go awry

Melvyn Bragg, The Adventure of English.

David Crystal, English as a Global Language.

Joan Pinkham, The Translators Guide to Chinglish.

Walter Benjamin, The Task of the Translator, in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections.

Chen Meilin/Hu Xiaoqiong, Towards the acceptability of China English. http://journals.cambridge.org.

Liu et al., Lost in Translation: Millions of Tourists to China are confused by a Myriad of Chinglish Misinterpretations. http://www.linguist.org.cn.

Niu Qiang/Martin Wolff, China and Chinese, or Chingland and Chinglish? http://journals.cambridge.org.

Wei Yun/Fei Jia, Using English in China. From Chinese Pidgin English through Chinglish to Chinese English and China English. http://journals.cambridge.org.

Some instances in life happen with such intensity that they may well be regarded as the starting point for a wonderful friendship or a lifelong passion. I had such a moment on July 25, 2000. I was about to get off a taxi near the Shanghai Foreign Languages University, where I had recently started my scholarship year as a Chinese major, when a neat sticker on the inside of the door told me: Dont forget to carry your thing.

I was immediately fascinated, and I began to look everywhere for signs of Chinglish. I traveled the provinces and spotted it throughout, often in the most unexpected places. I found it on hotel room doors and brightly lit highway billboards, construction sites and soccer balls, condoms and pencil boxes.

Chinglish exists because people travel and their language travels with them. Chinglish also exists because of Chinas opening to the world, the tourism industry, state propaganda mechanisms, and the Internet. In preparation for the 2008 Olympic Games, Beijing is gearing up an immense amount of manpower to eradicate Chinglish from the capital, and the Chinese government plans to extend this linguistic cleansing to the rest of the country as well. My aim is to show the nowadays endangered species of Chinglish in its natural habitat.

Many contributors to this book come from the academic world. Most of them fear their colleagues reactions and are uncertain about having their names revealed. For my part, I am in the privileged position to stick my head out for something I regard well worth the riska better understanding between China and the world.

Since Chinese grammar is virtually nonexistent regarding inflections, declinations, and past and future tenses, it offers more options to play around than many other languages. This makes Chinese a first-class creativity booster. Linguistic variations exist in any language, including German, my mother tongue; these variations possess a creative potential that we should cherish more. The reinterpretation of language allows for a tremendous amount of humor, and humor is, and always has been, a cross-cultural form of communication. Therefore this book is about passion, not mockery. It is my most sincere hope that this book is understood as a bridge rather than a border.

Chinglish is very often funny because of the sometimes scarily direct nature of the new meaning produced by the translation. A deformed man toilet in Shanghai or an anus hospital in Beijing is funny because it instantly destroys linguistic euphemisms we Westerners have carefully built up when talking about sensitive topics. Chinglish annihilates these conventions right away. Chinglish is right in your face.

Poetry is what gets lost in translation, writes American poet Robert Frost. In terms of Chinglish, hes plain wrong.

This book came as a surprise and the realization of a dream I have had for quite some time. Ever since I spotted my first Chinglish sign in Shanghai, I have wanted to let people know about this truly fascinating topic, and, more importantly, make them interested in China and its people.

I thank Gibbs Smith, Publisher for this opportunity, my editor Jared Smith for brushing up my Denglish, and especially Christopher Robbins for contacting me in the first place. Many thanks go to Nico Volland and Tia Thornton for their valuable comments and my friends and fellow travelers, especially Patricia Schetelig, who provided me with their Chinglish beauties over the years.

I thank my father for living the importance of writing every day.

And finally Id like to thank you, dear reader, for picking up this little picture book and for your interest in a country that will continue to fascinate and divide for years to come.

Oliver Lutz Radtke

Please share your thoughts at www.chinglish.de.

Nearly four hundred million people speak it as their mother tongue, another six hundred million as their second language. A billion are learning it, a third of the worlds population is exposed to it, and The Economist predicts that by 2050 half the world will be in some way proficient in it: English is globalizations number one language, the communicative tool for trade, techniques, and tacticians in foreign ministries around the world. English, that local Germanic dialect spoken by one hundred fifty thousand people in the fifth century who survived the perpetual threat of extinction by Danish invaders, has come a long way indeed. Non-native speakers now outnumber native speakers by a ratio of about three to one. How likely (or desirable) is it that they all speak the same?

You might ask, what is Chinglish, anyway? It depends on whom you ask. Chinese emigrants raising their children in English-speaking countries will probably answer: Chinglish is a useful mix of Mandarin or Cantonese terms with day-to-day English. It is indeed convenient to shorten a sentence such as I dont want to go now because it is too hot and it will be hard to find a parking lot anyway into Dont go la, hot la, tai mafan a. For the Chinese high-school teacher, Chinglish is the students unsuccessful attempts to understand English through a Chinese matrix, resulting in sentences such as Please hurry to walk or well be late or She was very miserable and her heart broke. However, the English-speaking traveler more frequently encounters Chinglish in the form of public signs rather than spoken oddities. This book displays examples of the latter category, since oral Chinglish is difficult to visualize. But no matter how one looks at the phenomenon, one thing is clear: Chinglish is not a language.

The harbinger of Chinglish might be found, according to some scholars, in Chinese Pidgin English, which came to life in the eighteenth century when the British established their first trading posts in Guangzhou. The term originated from the word business and served, according to the great Yale China scholar Jonathan Spence, to keep the differing communities in touch, by mixing words from Portuguese, Indian, English, and various Chinese dialects, and spelling them according to Chinese syntax. Some believe that the idiomatic expressions Long time no see or No can do have originated from that time. Others refer to the late Qing-Dynasty Empress Dowager Cixi, who forced Chinese villagers to migrate to the West in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Another candidate is the so-called Yangjingbang (named after a long-gone creek in Shanghai near todays Yanan Dong Lu, which had separated the British and French settlements), an integration of English into Mandarin in the era of Lu Xun, Chinas greatest twentieth-century writer. Very influential, too, are the large numbers of Chinese immigrants to the United States, not only those who came during the Gold Rush era but also those who, in the last twenty-five years since the beginning of Chinas policy of Reform and Opening, have emigrated in increasing numbers.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Chinglish : found in translation»

Look at similar books to Chinglish : found in translation. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Chinglish : found in translation and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.