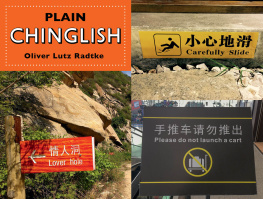

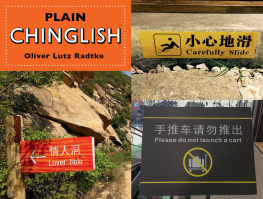

PLAIN

Chinglish

Oliver Lutz Radtke

Digital Edition 1.0

Text 2019 Oliver Radtke

Photos credited to Oliver Lutz Radtke unless noted otherwise.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission

from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Published by

Gibbs Smith

P.O. Box 667

Layton, Utah 84041

1.800.835.4993 orders

www.gibbs-smith.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018966887

ISBN: 9781423652663 (ebook)

This book is dedicated to my grandmother

Irmgard Radtke

(19242018). I miss her laughter.

Beijing (2011)

Contents

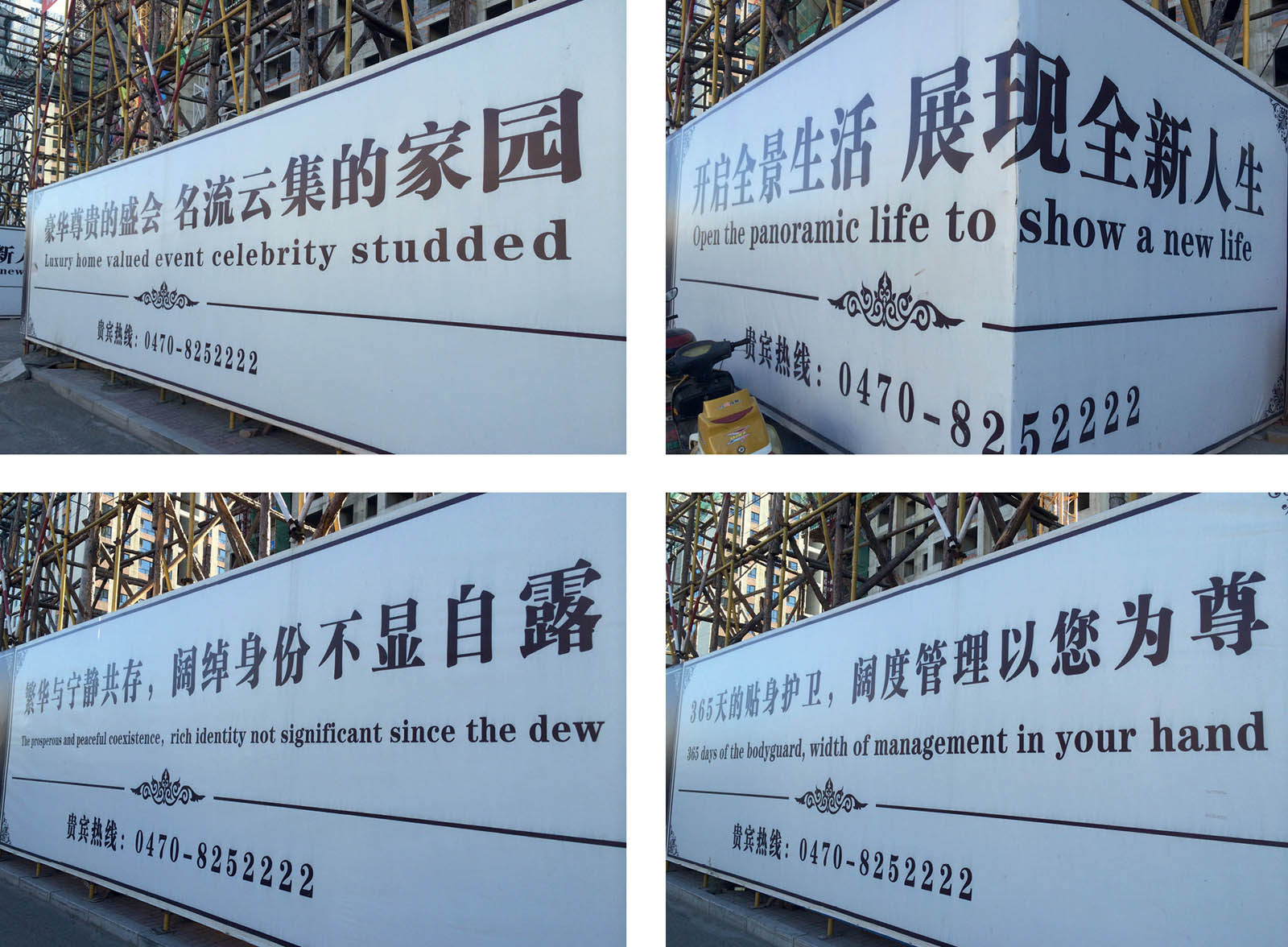

Hohot (2012)

Introduction

The prosperous and peaceful coexistence, rich identity notsignificant since the dew, screams the real estate billboard in Hohhot, the capitalof Chinas Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, in big brown letters. What it actuallywants to say is that the property on sale combines proximity to the city centerwhile still providing quiet, and because of its understated design your wealth wontshow (an aspect favored by many Chinese millionaires).With a smile, I reach for mycell phone to document the sign as I have done for almost twenty years while workingand traveling in China.

My fascination with Chinglish goes back to the year 2000, whenyou would find me as a Chinese studies major in Shanghai wandering wide-eyed aboutthe Huangpu river metropolis, jotting down new Chinglish observations in anotebookno smartphones back thenand trying to understand a new universe of wordsand ways to use them.

Chinglish, publicly accessible English translations (oftenconfused with Chinese grammar) was everywhere. The country was about to join theWorld Trade Organization (WTO) and was in the middle of a bidding process for the2008 Summer Olympic Gamesbilingual hilarities started to pop up everywhere. I feltprivileged to witness this blossoming period of Chinglish firsthand and to see howthe English language, or its unconsciously creative interpretations, visibly creptinto the linguistic landscape of the city.

But why would I as a German native undertake this mission todocument and explain Chinglish signs all over the country? Since I am neither anEnglish nor a Chinese native speaker I am blessed to observe the application of bothlanguages from a third culture vantage point, much less influenced by theirtraditions and conventions. I am equally curious about English as I am about Chineseand a humble learner of both, which has awarded me with the rare opportunity ofimmersing myself into two very different linguistic universes. Additionally, as theson of a retired proofreader, I was surely destined by family tradition to take acloser look at writing in the first place!

When I compiled the first volume of Chinglish ten years ago, things had already changed visibly from the daysof my early Shanghai observations. I lived in Beijing, which was gearing up animpressive amount of (mostly student) manpower to eradicate Chinglish from thecapital with the stated goal of getting rid of it nationwide. Fast forward ten yearslater and it is safe to say that the powers in place have been successful incleaning up a lot. First-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai look veryneatsome observers call it dullan indicator of the increased administrativeefficiency and raised awareness for better translation quality. But leave themetropoles and Chinglish hits you right in the face again, and will continue to doso in second- and third-tier cities like Changchun, Fuzhou, or Guiyang (not tomention the hundreds of fourth-tier ones) for many years to come. Chinglish is hereto stay.

Defining Chinglish

Chinglish can be viewed as a spoken and written phenomenon. Theformer is an oral hybrid during second language acquisition or a creative blend bysecond-generation Chinese growing up using both languages. This is an establishedacademic field, also looking at the emergence of Kongish, a conscious languagechoice in Hong Kong to strengthen local identity.

Chinglish in this book deals with bilingual public signage anditems with written interpretations of English. With the following pages, I inviteyou to understand that Chinglish can be more than just a quirky mix of an Englishdictionary and Chinese grammar.

Chinglish is firstly a by-product of Chinas sincere effortstoward modernization. It embodies the countrys linguistic contact zone with theworld. Chinglish is a laudable attempt by the state and the market to cater to anon-Chinese speaking audience, accommodating foreigners in the worlds linguafranca. However, even if resources are available, the sign makers awareness forhigh-quality translation is still oftentimes low, and the intended bilingual messageresults in a grandiose crash landing. With this book, I am in part certainly aimingto criticize official and non-official entities that should know better and just donot care where care is due, especially in critical areas such as hospitals,airports, allergy indications on product labels and menus, and so on. But, even moreso, I want to express my appreciation to individuals, organizations, and enterprisesthat try to cater to an international audience and do it, consciously or not, in adifferent way than native speakers would normally have it, making you smile andponder a message that you might have ignored otherwise.

The main producers of Chinglish are the state and the market.State Chinglish comes in the form of mostly anonymous communication with the generalpublic, consisting of (less friendly) notices and (very friendly) reminders. Bothrevolve around public services, directions, tourism, and public education. Thelatter strikes a non-Chinese reader as an unusual form of state communication inhighlighting a rather paternalistic attitude towards its citizens. On the one hand,this shows a form of official care, reminding its citizens not to spit everywhere inorder to avoid spreading infections and so on. On the other hand, the state acts asthe creator and reminder of civilized behavior, with many Chinese privatelyobjecting to this form of authority. Furthermore, the official party language, analready highly complex set of codes and expressions in Chinese, makes it almostimpossible to find non-clumsy sounding equivalents in English.

While state signs have improved a lot, the market economyprovides the real soil for Chinglish flowers to blossom: on shop signs, incommercials, and on productsespecially stationery and clothes. The latter two haveshed Chinese characters altogether, suggesting that English here is used as a formof projected cosmopolitanism with an exclusively domestic audience in mind, similarto Kanji sweaters or Chinese character tattoos in the West. The biggest Chinglishprovider these days is certainly the restaurant menu. Chinese dish names areparticularly rich with historical analogies, flowery imagery, and puns that willhardly ever cease to provide opportunities for Chinglish results, especially whenrelying on free online translation software.