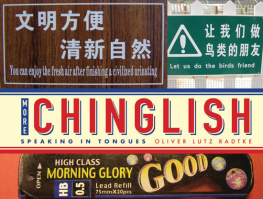

Oliver Lutz Radtke - More Chinglish : speaking in tongues

Here you can read online Oliver Lutz Radtke - More Chinglish : speaking in tongues full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Salt Lake City, year: 2009, publisher: Gibbs Smith, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:More Chinglish : speaking in tongues

- Author:

- Publisher:Gibbs Smith

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- City:Salt Lake City

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

More Chinglish : speaking in tongues: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "More Chinglish : speaking in tongues" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

More Chinglish : speaking in tongues — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "More Chinglish : speaking in tongues" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

More Chinglish

Digital Edition v1.0

Text 2009 Oliver Lutz Radtke

Photographs 2009 As noted

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Gibbs Smith, Publisher

PO Box 667

Layton, UT 84041

Orders: 1.800.835.4993

www.gibbs-smith.com

ISBN: 978-1-4236-0772-4

When I moved my limited private collection of fifty or so Chinglish beauties from a personal homepage to a blog in June 2005, I didnt assume that many people would care. I cared, and that was all that mattered.

Three years later, my blog now gets thousands of hits per week. My first book, Chinglish: Found in Translation, has sold tens of thousands of copies, and I have been privileged to appear in media around the world.

Obviously, people have an interest in the subject, whether its to ridicule errant Chinese authorities and translators, to reflect on experiences in China, or to use the collection as a classroom text.

But sometimes I wonder: Is this all leading in the right direction? For most of the world Im the funny guy, and in China Im a kind of savior, but both titles are only very partially correct. There are much less flattering titles to bear. If youre a politician, you are used to vituperations of any kind. But if youre a John Doe or Otto Normalverbraucher, as we say in German, its an interesting feeling to stick your head out for something you hold dearly while the anonymity of the Internet facilitates your receiving all manner of vilification. This happened especially during the first year my blog went online.

I am not arguing against correcting mistakes, but rather for a more relaxed attitude toward the so-called standardization of language. After all, Chinglish is a major contributor to the English language, and it also provides a counterweight to the burden of political correctness, which, especially in the United States, threatens to whitewash everything.

For me, my books and my blog are fun projects, no doubt about it. But they are also a way of showing continuous belief in something that has the potential of bringing people togetherpeople who might be different in many ways, but have so much more in common. I am more convinced than ever that Chinglish has to stay. Its a window into the Chinese mind, a phenomenon that goes beyond cheap jokes and finger pointing. Chinglish is right in your face. It challenges our linguistic conventions and, yes, it makes us laughabout ourselves.

I am writing this sitting in the Chinese capital, surrounded by Chinglish. Mind you, this is post-Olympics Beijing. The authorities didnt succeed: they didnt eradicate all Chinglish. They couldnt have. For me, thats the real highlight of the 29th Olympic Games.

Thanks go to my publisher, Gibbs Smith, for providing me with the opportunity of a second volume, and thanks go especially to my editor, Jared Smith, who isnt afraid of long-distance calls.

Thanks go to Lin Xueling for encouraging e-mails and invaluable input, Xiao A for stress management, and -Professor Victor Mair for his patience and passion.

Many thanks to the man who made me aware of the beauty that lies within foreign tonguesmy father.

And last but not least, many thanks to all the supporters of www.chinglish.de. Without you the online museum wouldnt be where it is today.

Oliver Radtke

Beijing, September 2008

When you fly to Beijing these days, somethings missing. At Beijing Capital International Airports Terminal 3, there is no longer a sign reading No entry on peacetime. The Chicken without Sexual Life is now absent from menus. And the ten-foot-high neon billboard reading Dongda Anus Hospital has disappeared. But you wonder, is Chinglish really gone? You step into one of the side streets near the Drum Tower and find it there in all its glory: a bar offering coffee with iron and a last rape soup, public parks inviting you to Let us do the birds friend and to Fall into water carefully. Happily, you realize that Chinglish is indestructible.

China is experiencing an unparalleled historical period of reform and opening, and in many ways, an anything goes attitude contributes to why life in China is so exciting. But at the same time, this attitude is also a significant contributor to a general sloppiness in many aspects of Chinese life. Chabuduo in Chinese, or works anyway in English, is a phrase that defines a lot of hasty production processes where quality should be a major concern.

Many people are fighting Chinglish, both on an official level, where it is a general embarrassment for the government, and on a personal level. David Tool, a retired army colonel from the United States, is one of the better-known protagonists, in Chinese newspapers regularly appearing under his Chinese name, Du Dawei. Since he came to Beijing seven years ago, Tool has made it his mission to eradicate broken English throughout the Chinese capital. When foreigners come here, I want them to understand Chinese culture, he says. I dont want them to make fun of it. An English professor at the citys International Studies University, Tool says he has corrected more than one million mistakes as a consultant for the Beijing Speaks Foreign Languages Committee, which has released twelve volumes of guidelines for medical signs, commercial signs, and gymnasiums. For his efforts, in 2006, the City of Beijing awarded Tool its highest honour, the Great Wall Friendship Award.

I sat down with Tool and Wang Xiaoming, director of the English Language Center of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), in a talk show on Beijing TV. It was an interesting discussion, since Tool and I both want the same thing: to introduce foreigners to the richness of Chinese culture without making them stop at the language barrier. While I laud individuals like Tool for their spirit and agree with the necessity of correcting hospital and other public signs that make life in Beijing less of a hassle, I usually fear that such efforts also take away a linguistic culture that can be seen as a facilitator, not an obstacle. So I was positively surprised to hear Wang Xiaoming say that despite the million signs they already corrected, both she and Tool are very much in favor of keeping certain Chinglish translations that carry the original meaning rather well, for example No Nearing for qing wu kaojinand Keep Space for baochi cheju. Unfortunately, its just us two on the committee who think this way, says Wang.

My collection of Chinglish signs has grown over the years to more than 1500 examples. I took a representative sample from my collection and came up with several unique categories where Chinglish is most likely to appear: commercial products, company signs, warnings, PR gibberish, public education, and restaurants and tourism.

The result: Chinglish for public education is by far the leader. By public education, I refer to such beauties as Be careful, dont be crowded or You can enjoy the fresh air after a civilized urinating. This confirms an important point: Chinglish is first and foremost a form of anonymous communication, mostly between official institutions and the public. It is openly displayed and often contains a schoolmasterly or motherly tone of instruction. In other words, Chinglish, with its educative tone and its anonymous top-bottom setting (we educate, you follow), is closely related to the mass education campaigns of Chinas Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (196676). Today, just as in the past, white characters on red banners are used to tell people how to act, and, by relation, who they are.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

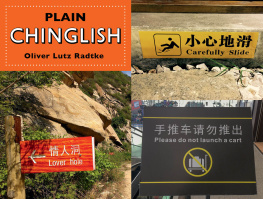

Similar books «More Chinglish : speaking in tongues»

Look at similar books to More Chinglish : speaking in tongues. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book More Chinglish : speaking in tongues and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.