Equipment

The board or go ban

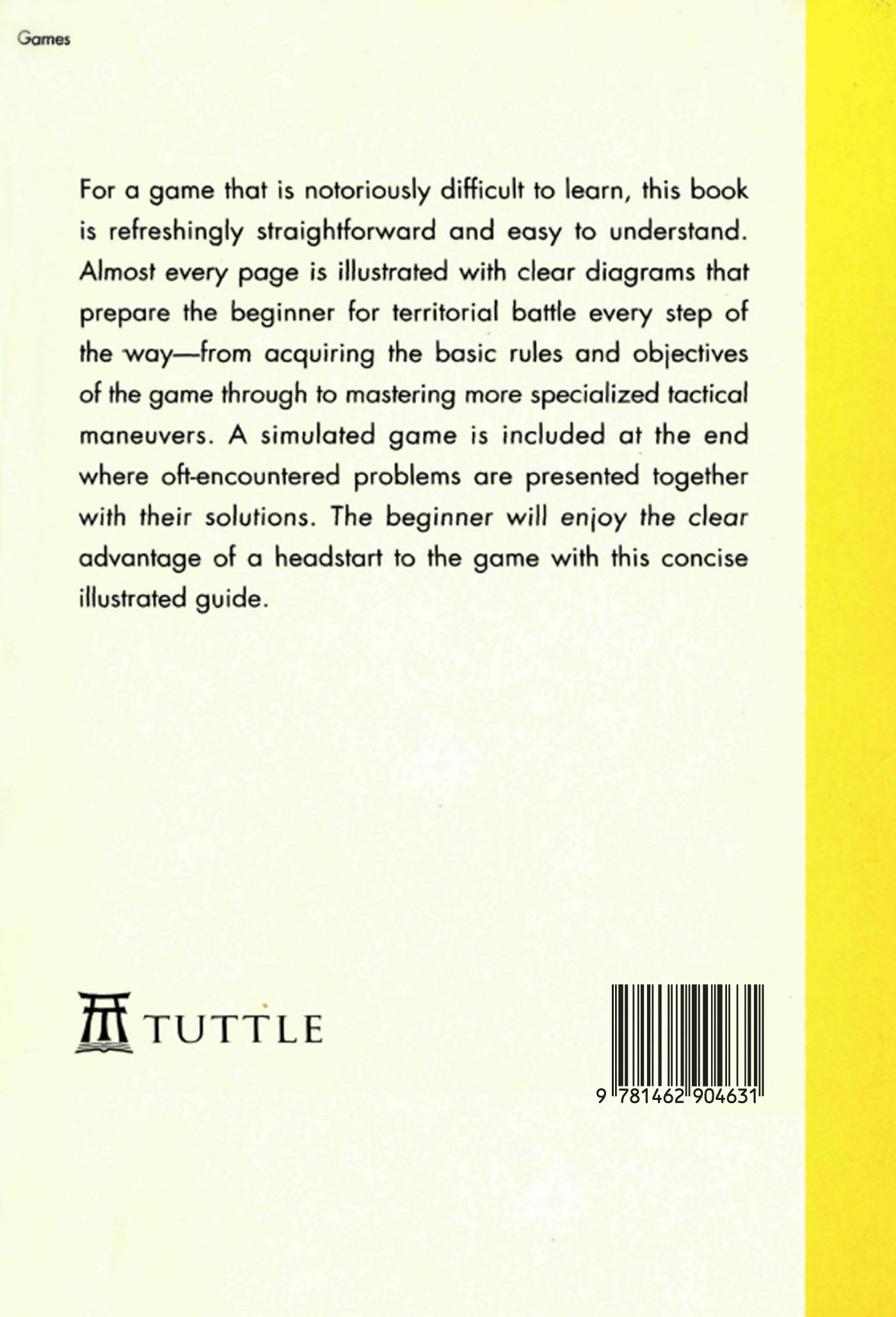

The board, or go ban as it is called in Japanese, is a solid block of wood, generally about four or five inches thick, resting upon four detachable legs. It is about 17 inches long and 16 inches wide. The board and legs are usually stained yellow.

The best boards are made of kaya ( Torreya Nucifera, or the famous Torrey pine of California). However, these boards are extremely expensive. Boards are also made of katsura (Japanese Judas tree), icho (gingko), or hinoki (Japanese cypress). Katsura boards, reasonable in price, are the most widely used today. Recently, flat boards without legs have been introduced, and are popular because they are more convenient and suitable when the game is played on a table or in a similar position.

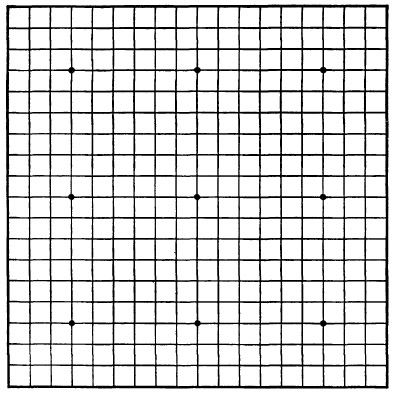

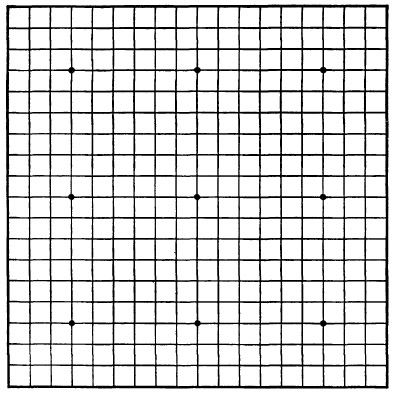

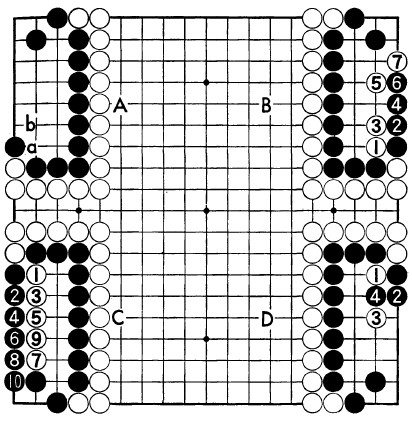

The board is crisscrossed by 19 vertical and 19 horizontal lines, forming 361 points of intersection, and there are nine dotted points on its surface. These are called hoshi which means star, and they are used by the weaker player in the event of a handicap game. As will be seen, this gives the weaker player an advantage. Diagram 1 shows the surface of a go ban.

Diagram 1

The surface of go ban

showing the nine dotted points called hoshi

The stones or go ishi

As mentioned above, there are two kinds of stones: white and black. The white stones are made from clam-shells that come from Miyazaki Prefecture in Kyushu, the southern part of Japan. They have a lustrous polish and are pleasant to the touch. The black stones are made of a special kind of stone from the Nachi cataract in Kishiu, in central Japan, and are called Nachi ishi. As a good set of stones is quite expensive, cheaper stones, made of hard glass, are widely utilized. There are 361 stones, corresponding to the number of the points of intersection on the board. One hundred and eighty are white and the remaining 181 are black. As the weaker player takes the black stones and is entitled to the first move, the extra stone is black. In actual play, about 150 stones of each color are sufficient to play a game. The stones are contained in lacquered boxes or go ke.

The stones in play are placed on the points of intersection of the lines and not on the squares as in chess. Once placed, they cannot be removed, remaining on the points where they are placed until the end of a game, except when they are captured.

A hint should be given the beginner not to grasp a large handful of stones in one hand and use it to feed the other. Each stone should be withdrawn from the box at the conclusion of the opponent's turn to play and only when it is required for immediate use.

It is not absolutely necessary to learn the correct way to handle stones, but, for your reference, it is as follows: grasp the stone lightly between middle and index fingers of the right hand, resting it lightly on the nail of the index fingeran act that requires some practice to perform gracefully.

Basic Tactics

Inasmuch as go is a game of strategy, in which there are many tactical procedures, it is necessary for beginners to learn at least some of the fundamental basic tactics. You should be able to master them without much difficulty if you remember what you have learned in the previous chapters.

Set forth below are some of the tactics needed to meet situations that develop during play.

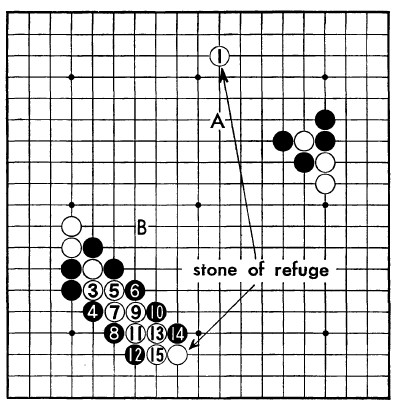

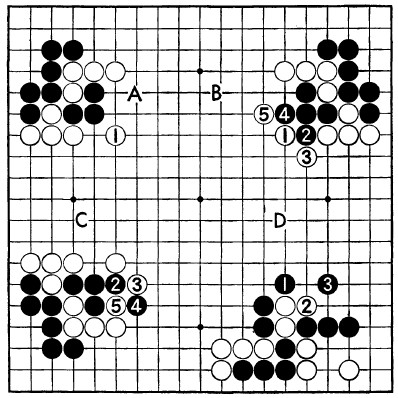

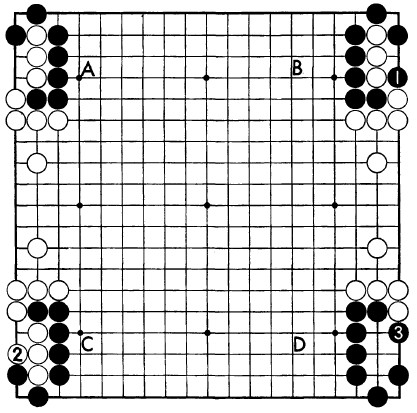

In Diagram 51 it is Black's play and he must play at 1, whereupon White attempts to live by playing at 2. Black has to play at 3, and the subsequent steps are taken as recorded. This results in the capture of the white stones upon reaching the edge of the board. This situation is called shicho which means "a running attack."

Therefore when such a position develops a shrewd player would not extend his losses in this way but would instead play elsewhere, abandoning temporarily the threatened stone.

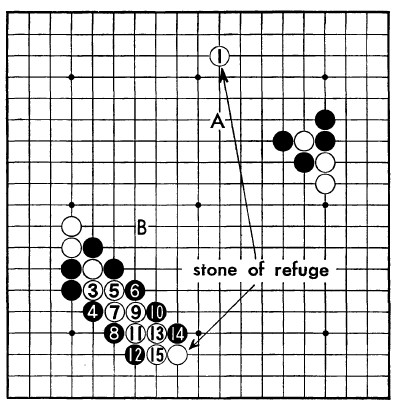

On the other hand, however, the case is not hopeless if there is a friendly stone in the line of flight, no matter how far off it may be. This stone is called shicho atari, which may be translated as "a stone of refuge from a running attack." A study of Diagram 52 shows the truth of this. As you can see, Black cannot capture the white stones in a shicho, because the threatened white stones are eventually connected with the stone of refuge as shown in Figure B. The single white stone marked as 1 in Figure A is the stone of refuge.

Diagram 52

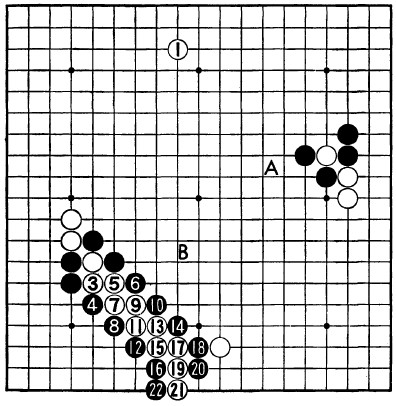

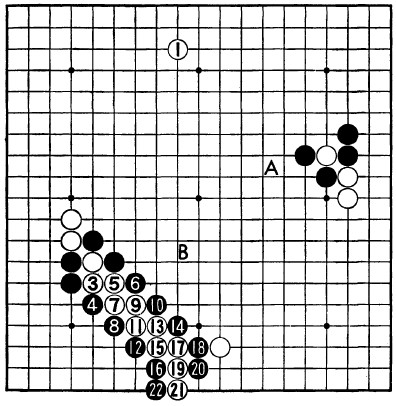

Diagram 53

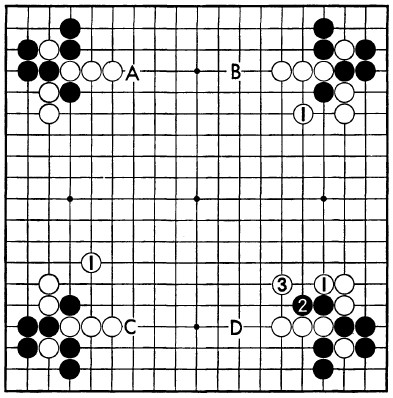

Diagram 54

If Black fails to notice the meaning of this white stone and plays at some other place on the board, White immediately attempts to escape by playing at 3 and eventually succeeds in connecting to the white single stone above mentioned. In this situation Black should not have tried to capture the white stone in this manner because now his own stones are in a position to be attacked by White in many directions.

In the situation shown in Diagram 53, Figure A, the waiting white stone is not posted on the line of progress, in which case the running attack is successful as indicated in Figure B. White must be careful not to misplace the stone of refuge in an attempt to escape from the running attack.

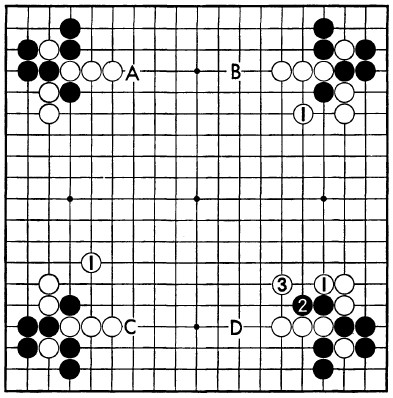

There are many ways for White to prevent the black stone from escape in Diagram 54, Figure A. The plays in Figures B and G are correct and these plays are called geta, which may be translated as "capping" plays. Figure D is a shicho which you have already learned: if Black tries to escape by playing at 2, White, needless to say, plays at 3, a capping play.

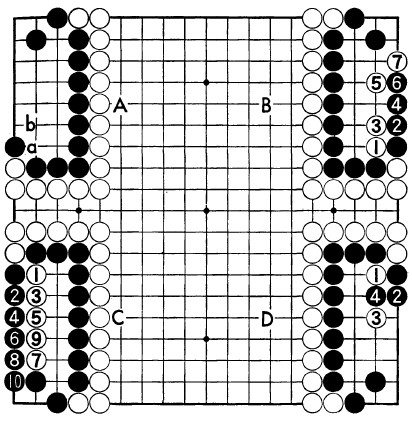

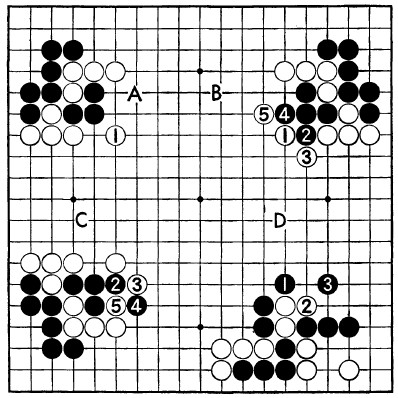

Diagram 55 is another example of a capping play. In this situation, there is no possibility for Black to find a way to escape. Figures B and G show you the truth of this.

Diagram 55

Diagram 56

Diagram 57

Similar cases frequently occur in actual games. If you memorize these plays, you will find no difficulty in preventing the escape of your opponent's stones.

Another example of a capping play is shown in Figure D, and from this example you should learn why the Black at 1 and 3 are essential in order to prevent the flight of the hostile stone.

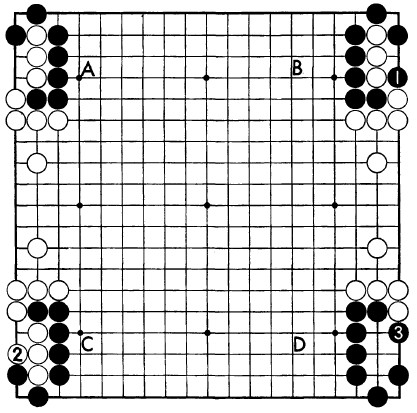

In the situation shown in Diagram 56, Figure A, Black must make an additional play either at "a" or "b" in order to defend his territory completely. If Black fails to do so, the one black stone will be captured by a capping play as shown in Figure B, resulting in a big loss of Black's territory. Figures G and D show two incorrect plays for White, in which cases Black loses nothing and, on the contrary, the white stones are dead.