VIVA LA PIZZA!

Copyright 2013 by Scott Wiener

First Melville House printing: November 2013

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

ISBN: 978-1-61219-307-6

eBook ISBN: 978-1-61219-308-3

Book design by Christopher King

A catalog record for this title is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

Contents

THE ART OF THE PIZZA BOX

INTRODUCTION

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PIZZA BOX

The story of the pizza box is also the story of pizza, which began its existence as a humble street food in southern Italy. As far back as the sixteenth century, leftover dough was placed in bread ovens as a tool to cool down the hearth; the dough absorbed heat, and leftover produce or pork fat was placed on top to prevent it from inflating due to steam buildup. The resulting pies were sold from the bakery counter or on the street, sometimes by mobile vendors who distributed pizza in a stufa, a metal vessel used as a warmer that was a predecessor to the modern pizza box. Concepts like pizza by the slice and home delivery have their roots in the hectic port city of Naples, a town whose low position in Italys cultural hierarchy kept it isolated from the rest of the country. Italians did their best to avoid Naples and anything Neapolitan, so pizza never spread up the boot.

Pizzas first expansion out of southern Italy occurred in the late nineteenth century, when political and economic factors drove impoverished citizens to find work in the growing industrial sector of the United States. Dozens of Little Italys developed in major cities, including Trenton, New Haven, Providence, St. Louis, Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. Pizza was then introduced to the greater Italian diaspora as a snack food, but since Italian neighborhoods were often quite small, it never needed to travel far enough to necessitate a box. Cheap newsprint provided pizzas only packaging at the time, and it remained this way for the first half of the twentieth century.

Exposure to Italian food and culture later inspired droves of American GIs to bring the dish back home after World War II. It was essentially the first time that non-Italians were eating pizza, and it resulted in a seismic shift in global pizza consumption that were still feeling today.

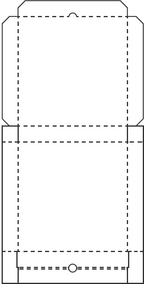

A Walker-style blank as it is delivered to pizzerias

The original corrugated Dominos Pizza box, designed by the Triad company to improve stability and insulation

Once the label of ethnic cuisine was removed, American interest in pizza grew exponentially, and soon American pizza took its own path. Ingredient availability and social factors led to regional variations across the country. The dry heat of New Yorks coal ovens produced thin, beautifully charred pizzas; avoidance of expensive mozzarella cheese led to tomato pies in Trenton and Philadelphia; and the Midwestern appetite paved the way for the development of the deep-dish pizza in 1940s Chicago.

Soon pizza was everywhere, and everyone was eating it. Moreover, everybody was taking it to go. Paperboard bakery boxes were an early mode of American pizza transportation. Some boxes had pre-glued corners that flattened down for shipping and easily popped into place for use. But the high cost of producing pre-glued boxes pushed self-locking paperboard to the forefront. These boxes shipped as a stack of cut and scored blanks whose front and back walls easily locked into adjacent sidewall slots.

The major problem with these paperboard or clay boxes is that they arent very sturdy. Unlike their intended cargo of dry cookies and cake, steaming hot pizza has a tendency to weaken a box from the inside. Even empty clay boxes were a hazard in busy pizzerias; their instability threatened spontaneous avalanches. The solution came at the request of a growing pizza chain called Dominos Pizza, whose founder, Tom Monaghan, enlisted a corrugated box company called Triad to solve the problem. In 1966, after some serious tinkering, a box was finally constructed to suit the needs of what was then only a four-store chain. As a better insulator and a sturdier structure, the corrugated container initiated a new era in the history of the pizza box.

Big Mamas & Papas Pizzeria in Los Angeles offers a fifty-four-inch square pizza that is packaged in the worlds largest commercially available pizza box. The pizza is so large that a custom extension is attached to the oven for added space and support. It feeds fifty to seventy people and must be delivered on a roof-mounted car rack because it cant fit inside any standard automobile. The pizza costs $218 (with tax), plus $15 per topping, and delivery starts at $30 but escalates with distance. At least the box is free.

Large pizza operators eventually realized the marketing potential of their box tops and started printing their names and logos in the 1960s. Mom-and-pop pizzerias caught on more than a decade later with their own short-run semi-custom boxes. Pizzerias had their names printed alongside any combination of generic images (the boot of Italy, a mustachioed chef, Italian flags). It wasnt until the late 1990s that four-color process printing turned pizza boxes into art. Designs were broken down into cyan, magenta, yellow, and black components, and printed one color at a time as small dots with flexographic printing machines. Box companies wanted to show off their full capabilities and began courting customers to submit art. Roma Foods, a distributor in the northeast, dove in headfirst with a series of full-color designs starting around 1995 (see ), and others quickly followed.

As beautiful as they may have been, full-color prints didnt catch on with American pizzerias due to their high costs. The trend overseas is entirely different, particularly in pizzas birthplace of Naples. According to the most prolific pizza box artist, Luca Ciancio, Italian box art is superior to that of all other countries because of a greater respect for the product within. On a mechanical level, the printed box industry in Italy is much younger than that in America, and newer machines allow for more accurate reproductions of complex designs.

Unlike these advancements in pizza box art, little has changed with box technology. The corrugated pizza box has been a simple and cost-effective solution since the 1970s, yet hundreds of inventors have attempted to improve upon it. In 1991, a patent was filed for a box that breaks down into serving plates. A few chains even auditioned boxes that could fit a second pizza stacked on top of the first. Several circular pizza containers were patented in the 1990s, theoretically better suited for transporting likewise circular pizzas. Then there were boxes with built-in support systems to protect the container and the pizza from each other. One of the more fascinating patents is called Disposable Pizza-Blotting Composite and Box Assembly, poised to solve the problem of overly greasy pizza with a self-blotting lid. Another favorite is the Level-Indicating Pizza Box, a patent filed by J. Gus Prokopis in 1998. The box has a built-in spirit level so the user can be sure theyre carrying their pizza correctly. All interesting solutions for problems the market doesnt deem necessary to fix.