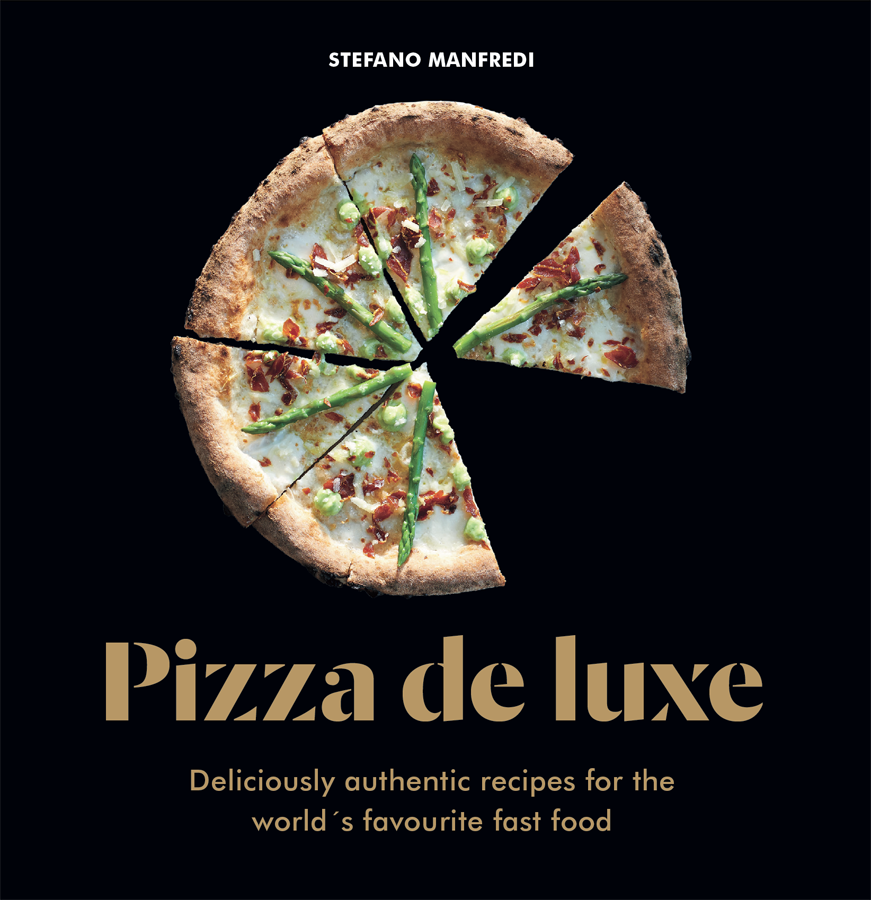

Discover how easy it is to create the healthiest, tastiest pizza this side of Naples. Pizza can be thin, thick, crisp, chewy, round, square, filled, fried or sweet but the quality of the pizza is always defined by the quality of the flour, dough and toppings. Stefano Manfredi, Sydneys award-winning pizza maestro, takes the worlds favourite fast food back to its origins as a deliciously healthy and simple meal for everyone to enjoy.

Stefano Manfredi is one of Australias leading exponents of modern Italian cuisine, translating the flavours and recipes of his Lombardy childhood. For more than three decades Stefano has owned and operated restaurants in Sydney, most notably the award-winning Restaurant Manfredi and bel mondo and, more recently, Pizzaperta Manfredi. He has published five books and made numerous TV appearances in Australia and overseas.

New wave new pizza

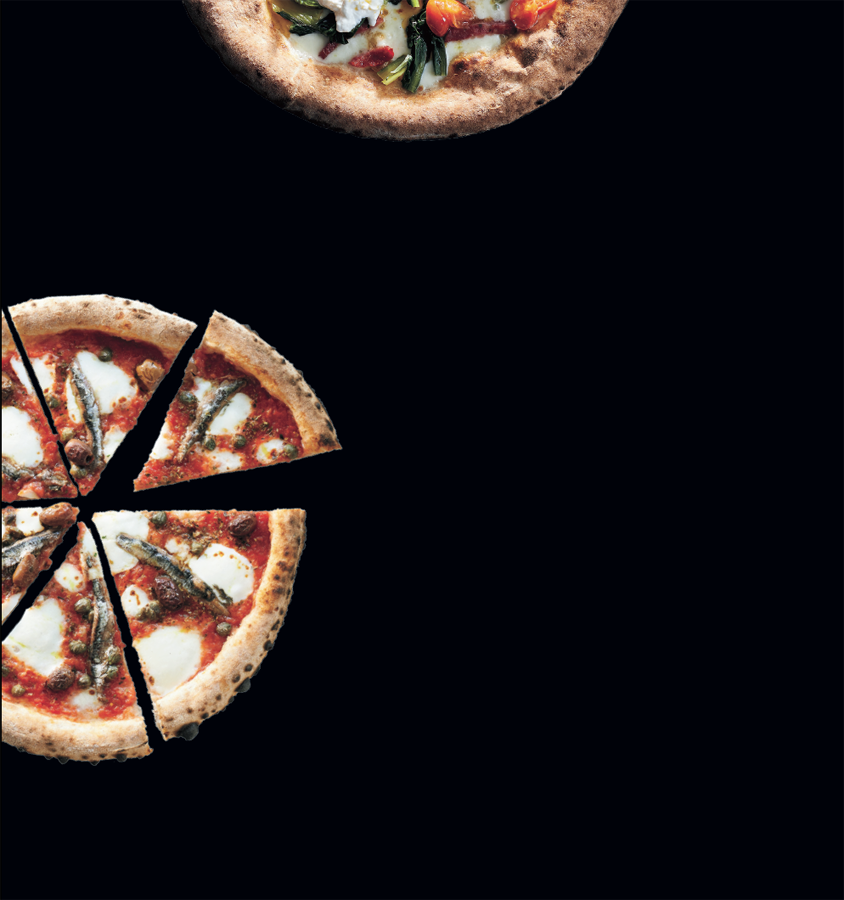

Pizza is probably the worlds most popular fast food and wherever it has gone, it has taken on the characteristics of its new home. While Italy, and more precisely Naples, is where it all began, theres no doubt that pizza now belongs to the world. But something exciting is happening in pizzas spiritual home. What I call the new wave of pizza has been gaining momentum in Italy in the last decade and that inspiring movement is the focus of this book.

Ive been researching pizza in Italy for many years now and Ive noticed a huge change in the way it is made at every step of the process. It has been led by chefs/pizzaioli whose curiosity and eye for quality has led them back to the fundamental building blocks of pizza-making, from the growing of the grain and the milling process to temperatures, fermentation and maturation times for the dough.

Where has this change in pizza-making led us? Much like the recent movement away from industrial white bread towards artisan loaves with natural leavening and specialist flours, its a look back as well as a step forward. New wave pizza-making is a movement that returns to pizzas origins before industrial flour milling, while at the same time using modern advances in stone milling, machinery and oven technologies.

This step forward in pizza-making has by necessity taken place outside Naples. If you look closely at pizza kitchens in Naples youll find that many of them use highly refined 00 flour, as outlined by one of the groups set up to standardise Naples-style pizza. This flour is relatively cheap, has had the wheat bran and germ removed in the refining process and has the consistency of talcum powder. Now, there is nothing wrong with this and the use of 00 flour more or less defines the Naples-style pizza as we know it today, but what happens when you use different flours, milled with stone and free of these strictures? What can be achieved when these flours are then used with different types of fermentation procedures? These are some of the questions we will look at in this book.

After all, even when pizza appeared in Naples in the first half of the eighteenth century, it would be over a century before the modern roller mill was invented. So, for at least a hundred years, stone-milled flour was used to make pizza. Granted, the bran was partly sifted out by pizzaioli even back then, but the grain was milled in its entirety, and this is fundamental to its structure. The roller mill brought us white flour. White flour meant uniformity, consistency and less technical ability needed on the part of the pizzaioli. As well, this flour lasts a long time and can therefore be exported and used to make a similar quality product around the world.

The other feature of new wave pizza is the focus on quality ingredients to go on top. With the exponential spread of pizza post World War II and, more recently, globalisation, this fast food has become devalued. In Italy, the margin on a typical pizza is so small that many of the pizzerie have developed a way to use cheap flour, short fermentation and maturation times, and poor ingredients to remain profitable. Now, not everyone adheres to these minimums, but with price pressures dictated by the market, the fact that stoneground flour costs more and that long, indirect fermentation methods take longer to make and are more involved, there is an incentive to take the easiest route. This approach is not just limited to Italy. As the pizza of Italy, and Naples in particular, is seen worldwide as a benchmark, the world for the most part follows.

This book will take the reader through what we do at my pizzeria, Pizzaperta Manfredi in Sydney, Australia. I have been a chef, running restaurants of the highest quality, for over 30 years. I have studied the methods and procedures of some of the protagonists of the new wave pizza movement in Italy and this book is the result.

My hope is that the information here will guide home cooks and professionals alike to explore the possibilities of pizza-making and to take pizza back to what it once was a healthy and delicious fast food.

STEFANO MANFREDI

What is pizza?

Pizza is a descendant of flatbread, the worlds most ancient bread. People starting making flatbread as soon as they learnt to grind grain, mix it with water, then cook it on hot stones, a griddle or in a makeshift oven. Whether it was made from corn, rice, potato, wheat, yam or another farinaceous edible plant, the flatbread sprang up in various parts of the world as people had the same idea. It was the first bread and it not only helped to hold other foods, but could be carried around and stored easily as a delicious snack or meal.

It appears that the version of pizza we know today the round, puffy-bordered, wood-fired type was born in Naples and was mostly confined to that city for over 200 years, as were the specialist pizzerie and pizzaioli who made pizza, along with the development of the special ovens that cooked it. In 1884, in her book Il Ventre di Napoli , Matilde Serao describes an attempt to open a pizzeria in Rome, just 200 kilometres (125 miles) to the north of Naples. It was a novelty for a while, but it ended badly, with the entrepreneur going broke. Sophisticated Rome looked down on this street food from the south.

The two centuries of isolation were essential for the refinement of pizza in Naples, which at the time was one of the most populous cities in Europe. Back then Naples was not the sprawling city it is today. It was confined to a much smaller area, and was one of the most densely populated and poorest cities on the continent. People lived in small rooms in buildings of up to seven storeys, a contrast to other European cities of the time whose buildings were, at most, half as high. Cooking was difficult and dangerous in these cramped conditions. A visit to the old part of the city today will attest to the narrow lanes and the density of the housing.