spotted eagle-owl

This detailed shot of the Spotted Eagle-owls downy feathers shows that the barbs of the feather dont connect with one another, giving the feather a hairlike appearance that allows more warm air to be trapped in the down.

Introduction and caption text copyright 2016 by Robert Clark.

Images copyright 2016 by Robert Clark.

Preface copyright 2016 by Carl Zimmer.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form

without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4521-4892-2 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clark, Robert, 1961- author photographer.

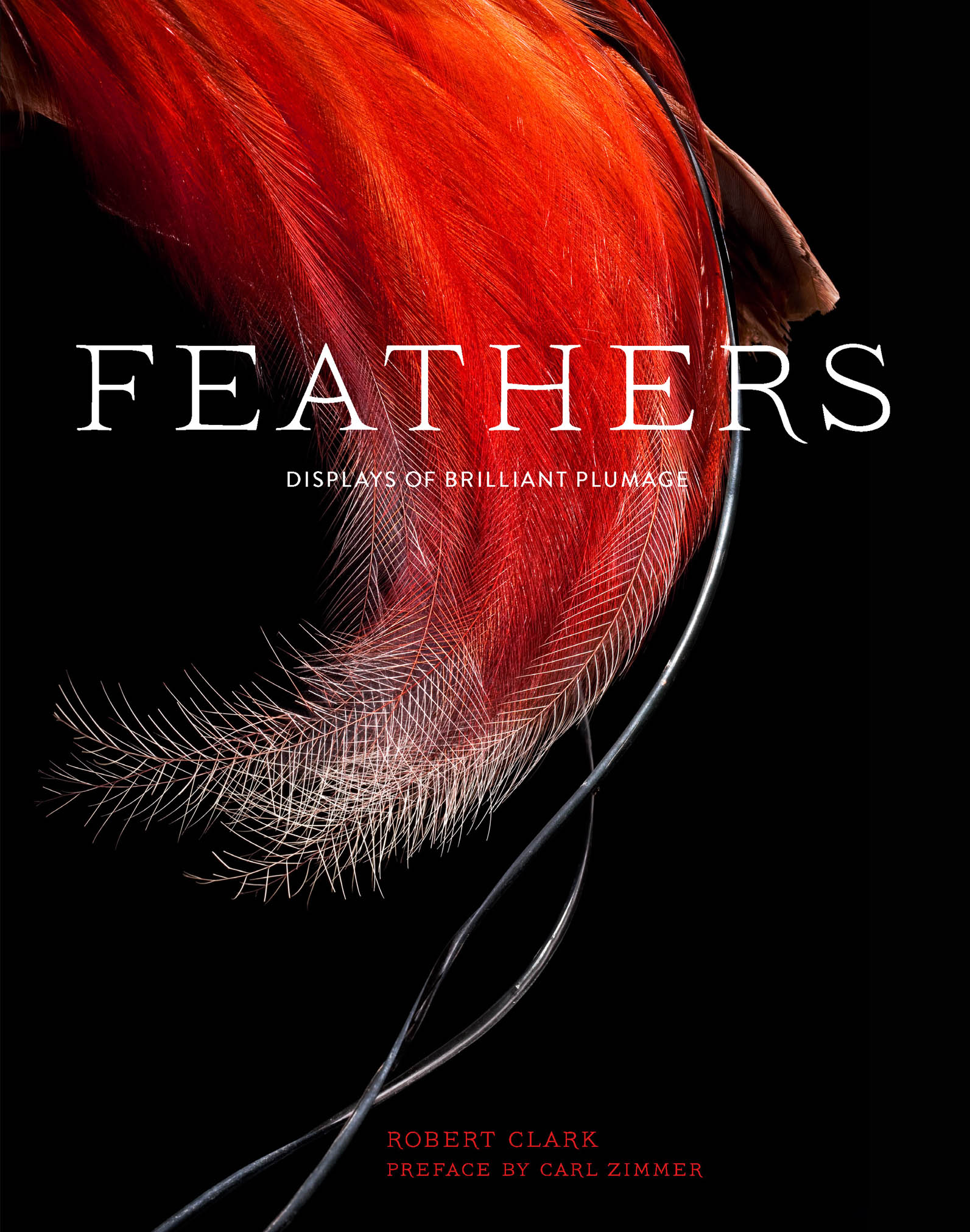

Feathers / Robert Clark.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4521-3989-0 (hc)

1. FeathersMorphology. 2. FeathersPictorial works.

3. Photography of birds. I. Title.

QL697.4.C54 2016

598.1470222dc23

2015026260

Design by Sara Schneider

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

acknowledgments

The creation of Feathers was an education for me. Before I began this project, I had no idea of the complexity, the origins, and the beauty that make up the history of feathers.

I could never begin a project like this without the help of National Geographic, which gave me the initial assignment that inspired this book. The research, planning, and critical eye of their deputy director of photography and a wonderful photo editor, Kurt Mutchler, provided me with constant encouragement and inspired me to learn more about the history of feathers.

During my photography and research I was able to work with and get advice from great minds like Xu Xing of the Chinese Academy of Science, and Rick Prum, the William Robertson Coe Professor of Ornithology and Head Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at Yale University, who helped me understand the broad strokes of the evolutionary story of feathers. Jakob Vinther, PhD, at Yale and Ryan Carney, PhD, at Brown were invaluable to my understanding of fossil evidence.

Numerous museums played a critical role in the making of this book: the Institute of Zoology and Zoological Museum at the University of Hamburg, the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, the Museum of Natural History at Humboldt University of Berlin, and the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature in Lioaning, China. The feather collections of the Prum Laboratory at Yale, the Peabody Museum, and those of Peter Mullen, PhD, and Gabriel Hartman added dimension and beauty to these pages.

When it came to the production and preparation of the book, I couldnt have done this without Parker Frierbachs hard work, research, assistance, and passion for the project. I was lucky to have someone so interested in the subject and dedicated to the books beautiful completion.

The editors at Chronicle Books, Bridget Watson Payne and Rachel Hiles, guided this project from an idea to the pages with grace and understanding. Thank you.

The people in my lifemy wife, Lai Ling, and daughter, Lolaare the two wings of my life that give flight to any and all of my best ideas.

preface

by carl zimmer

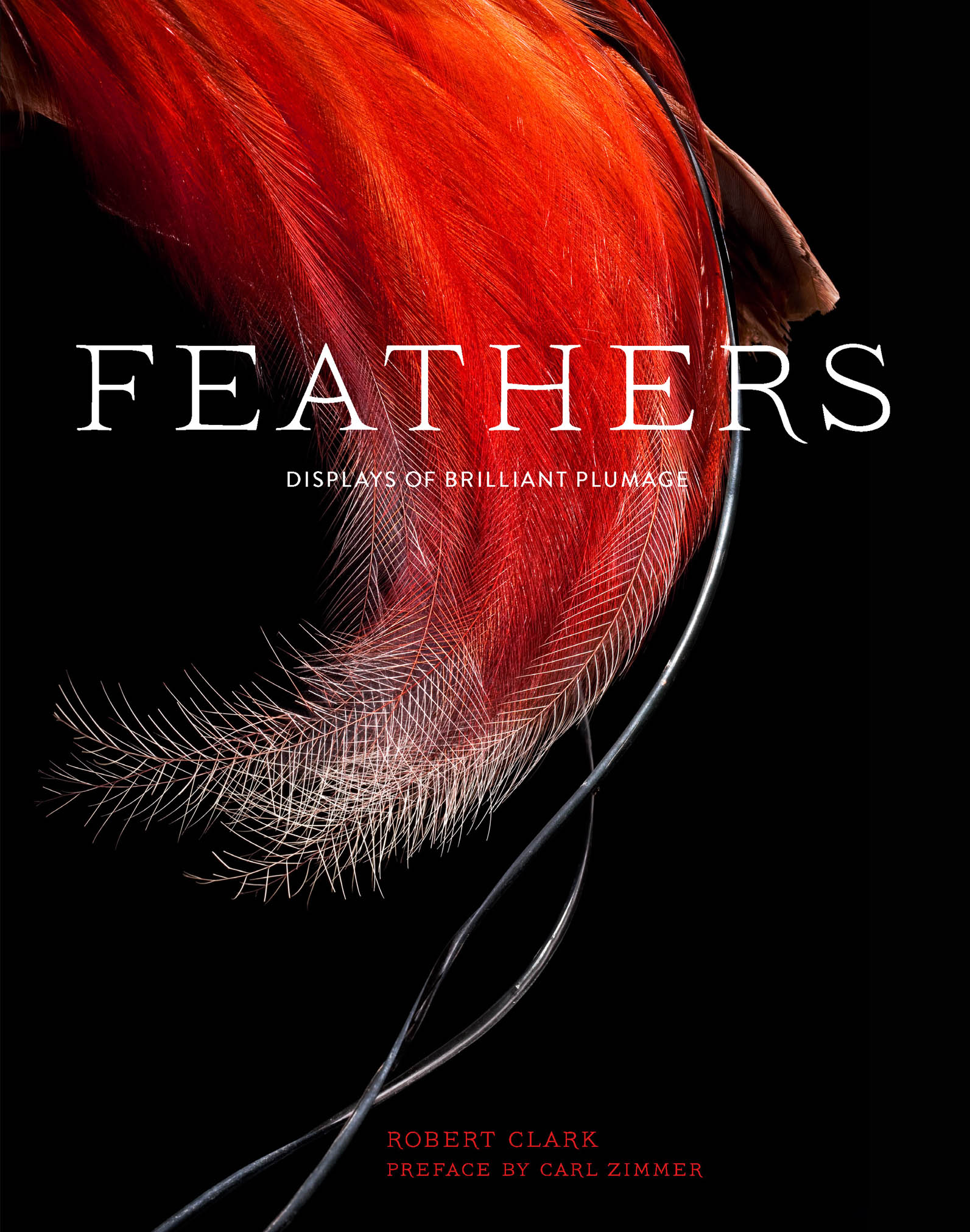

I live near New Haven, a small city on the coast of Connecticut. It is hardly a wildlife refuge, and yet theres always some astonishing biology on display, if you just think to look for it. The Pigeons strutting across the town green show off their iridescent pink feathers with each bob of their heads. Goldfinches shoot among New Havens bird-feeders like lemons fired from catapults. Crows congregate in parking lots, their feathers blacker than the asphalt underfoot. In the streams and marshes of New Havens parks, the Egrets stalking fish look like bleached feathered statues. Seagulls drift overhead, carried by the currents from Long Island Sound, their feathers the color of fireplace cinders. Each bird has over a thousand feathers, and in a single day in New Haven, you could easily see a million of them. And yet, unless you push your brain in a birdish direction, you might not give those feathers a single thought.

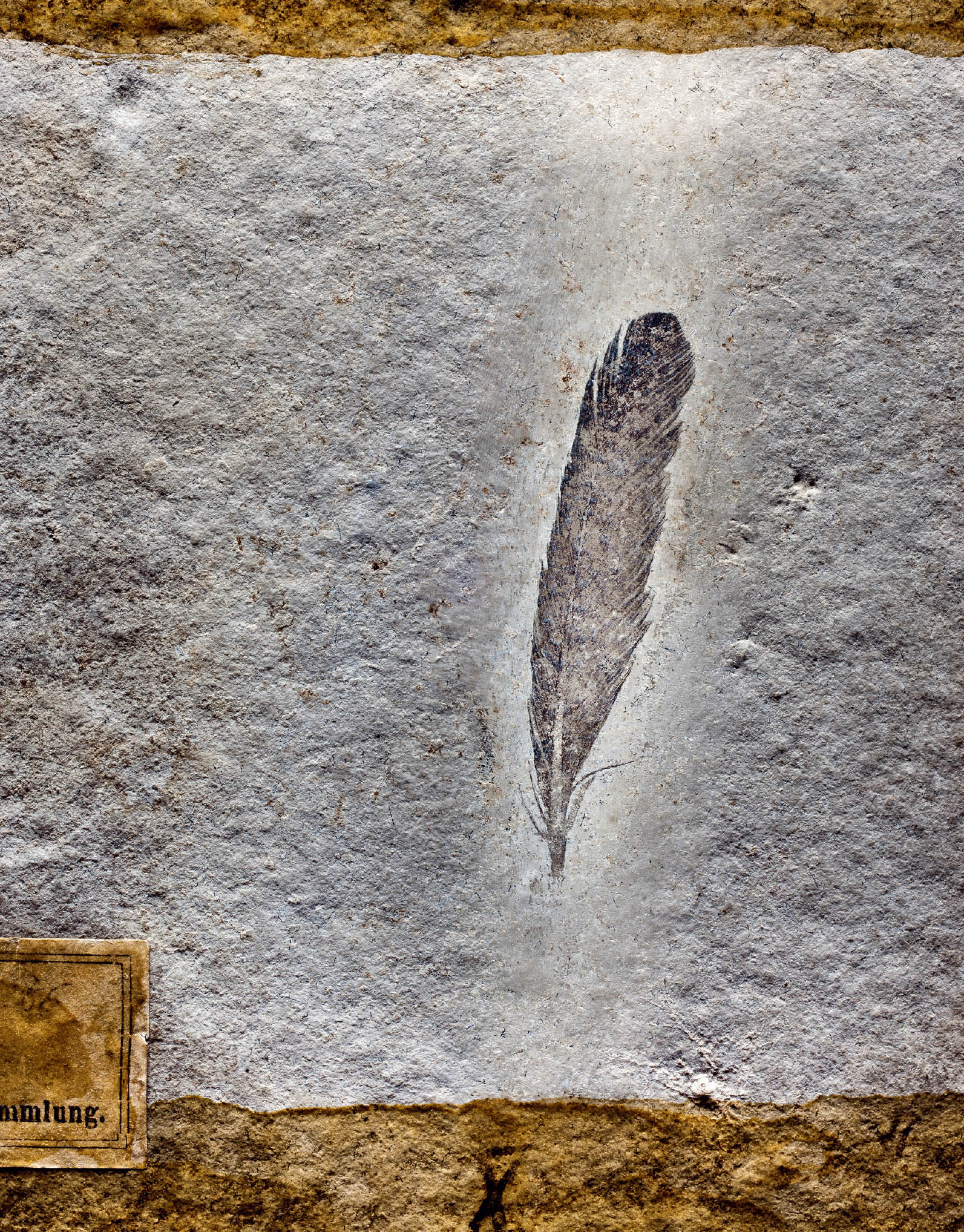

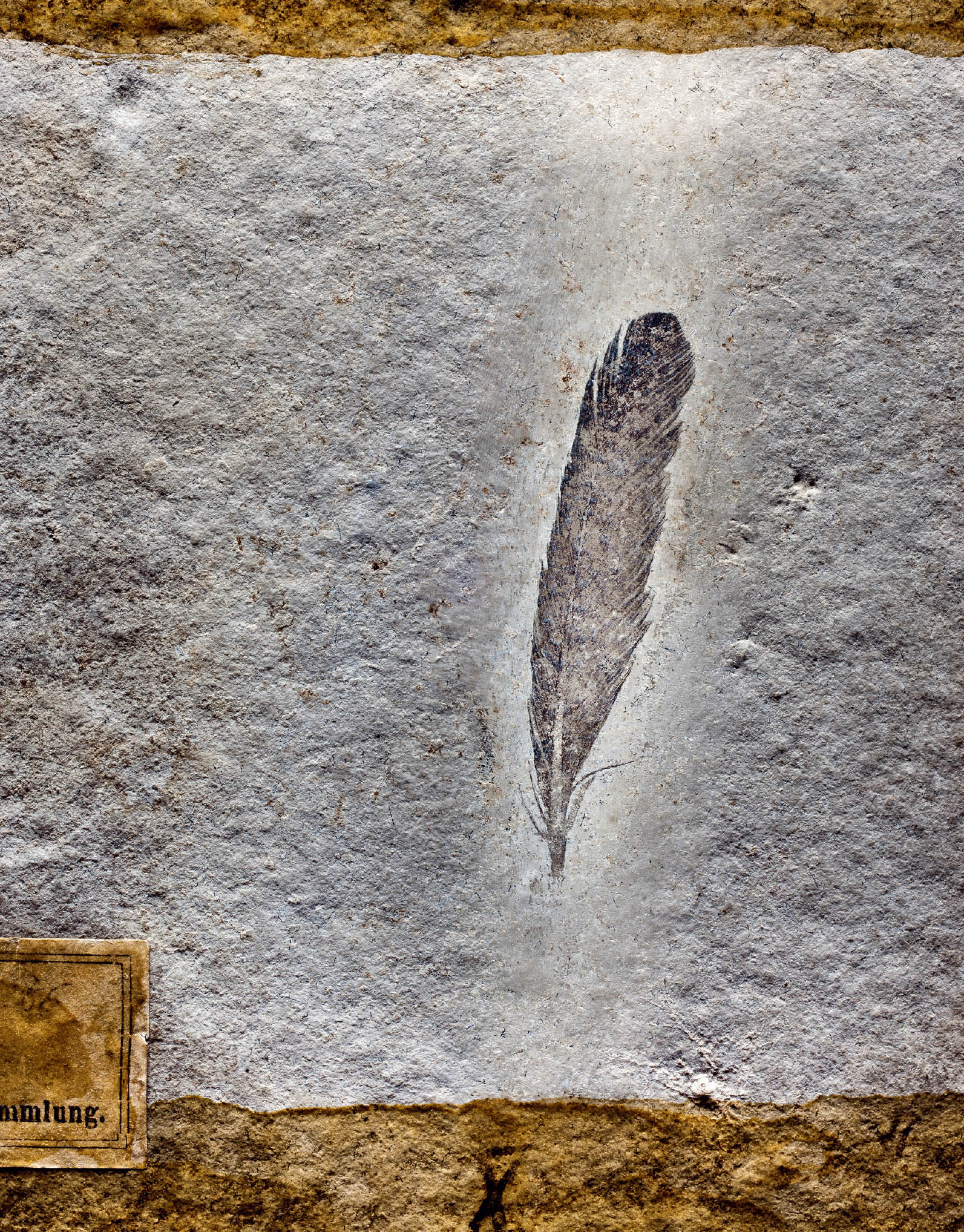

Thats a shame, because there is no better way in our ordinary lives to confront evolutions riot of invention and beauty. The earliest evolutionary hints of feathers can be found in the fossils of dinosaurs. Once people dreamed of Tyrannosaurus rex covered in scales. Today, science has covered the giant reptile in an improbable fuzz. As the dinosaur evolutionary tree sprouted new branches, some species gained more elaborate plumage. Simple bristles began to split into downy feathers. Others took on the shapes of pennants. Over millions of years, more kinds of feathers evolved, and small dinosaurs probably began to use them to help them move around. According to one theory, dinosaurs initially flapped their arms up and down to help them climb up steep inclines or down steep slopes. Feathery dinosaurs may have also used their plumage as parachutes, extending their leaps from branch to branch, or tree to ground. One lineage of these dinosaurs evolved skeletons and muscles that could harness the full power of feathers, flapping their arms up and down to generate fully powered flight.

Scientists can gain clues to the evolution of feathers not only by looking at fossils, but also by studying how they develop in bird embryos. There are outgrowths of cell clumps in the skin called placodes. It only takes slight tweaks in the genes that are active in placodes to cause them to produce the shaft of a feather instead of, say, a reptile scale. Feathers are thus an evolutionary rejiggering, rather than something that sprang out of the void. Birds also evolved new variations on the proteins found in other animals, producing special forms of keratin and other proteins that give their feathers different colors and physical properties, each suited to a different function.

And how many other functions there are! A bird can use some of its feathers to fly, others to stay warm, and still others to attract a mate. And among the ten thousand species of living birds, evolution has produced a staggering variety of feathers for each of those functions. Penguins, for example, produce tiny, nub-like feathers on their wings that keep them warm in the Antarctic Ocean while also allowing them to, in effect, fly through water. Owls, on the other hand, grow feathers on their wings that muffle the sound of their flight as they swoop in on their victims. The tail feathers of a Lyrebird grow to elegant twisted heights to attract a mate. The Club-winged Manakin has feathers that produce violin-like notes when flapped. The female Club-winged Manakin doesnt choose a mate based on how his feathers look so much as how they sound.

Even a city like New Haven can offer some of that diversity, if only we open our eyes and minds to it. But the world of feathers stretches far beyond Pigeons and Goldfinches. In this gorgeous book, photographer Robert Clark shows us feathers in a scope that few of us ever imagined. In the process, he demonstrates how inventive evolution can be.

Next page