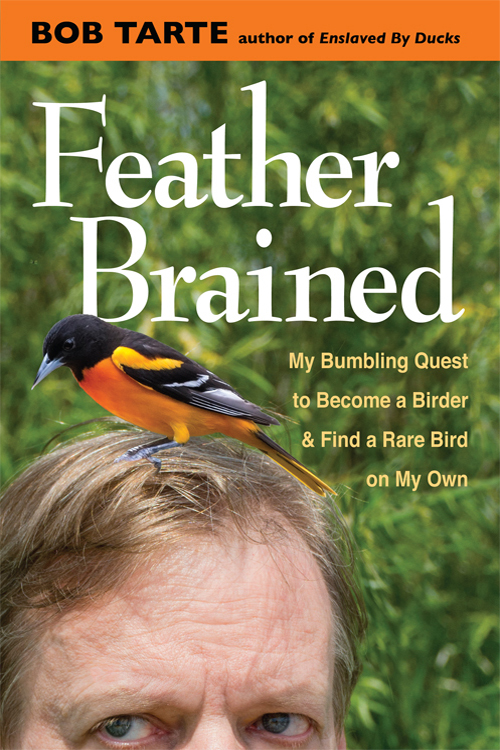

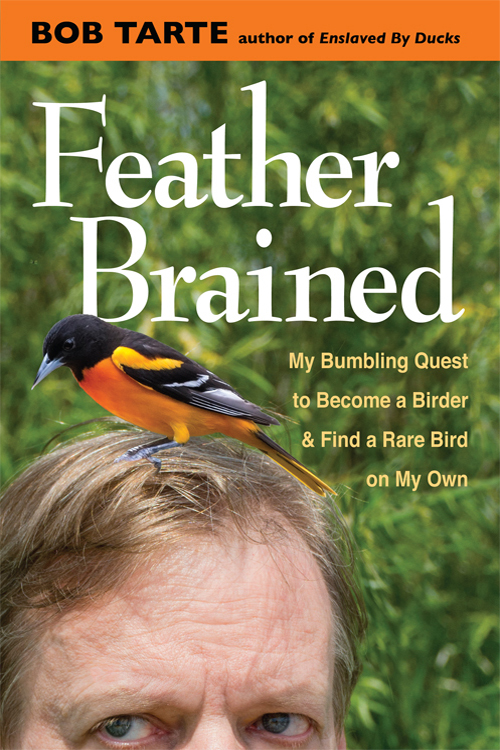

Feather Brained

Feather Brained

My Bumbling Quest to Become a Birder and Find a Rare Bird on My Own

Bob Tarte

University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Copyright 2016 by Bob Tarte

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tarte, Bob.

Title: Feather brained : my bumbling quest to become a birder and find a rare bird on my own / Bob Tarte.

Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015048912| ISBN 9780472119868 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472121885 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Bird watchersAnecdotes. | Bird watchingAnecdotes.

Classification: LCC QL677.5 .T285 2016 | DDC 598.072/34dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015048912

An excerpt from Keith Taylors poem Chasing the Ancient Murrelet from his book The Ancient Murrelet is used with kind permission of Alice Greene & Co.

Kind enough to contribute excellent photographs are Darlene Friedman (rose-breasted grosbeak, chapter 1; long-eared owl, chapter 6; red-headed woodpecker, chapter 13); Allen Chartier (rufous hummingbird), chapter 4; Caleb Putnam (yellow-rumped warbler), chapter 7; Karl Overman (ancient murrelet), chapter 10; and Bill Holm (author photo). All other photos are by the author.

To my friend Bill Holm,

discoverer of the special bird-attracting fluid

Also by Bob Tarte

Enslaved by Ducks

Fowl Weather

Kitty Cornered

Contents

The Green Book and the Redhead

I should have listened to my parents. More than fifty years ago, they had warned me about associating with the wrong sorts of people for fear of what would happen to my priorities in life. First they had railed against cheats and liars, thieves, swindlers, braggarts, and the morally lax. When I got older, drug users and dropouts from society topped the list. Though they had never specifically mentioned birders, I should have had the common sense to steer clear of their influence, too.

Now look what had become of me. On a sunny June morning I had ducked out of work to skulk around a sewage pond.

It was pleasant as sewage ponds go. No foul odors, chemical or organic, assaulted my nostrils as I skulked. Mallards paddled across water that looked clear enough to sit inside a drinking glass, while a flock of sheep munched on bright green lawns. A bell jangled in the distance, bringing back not altogether fond memories of childhood as shrieking kids poured out of a school behind the facility toward a row of buses. A manicured housing development framed the south side of the property. A flooded field awash with swallows and red-winged blackbirds lay to the north. If you didnt know any better, you might consider it to be a prime spot for a picnic. But it was a sewage pond. There was no way around the fact. And I had spent an hour searching the sewage pond for birds.

As I scanned the pond edges through binoculars I kept an eye on the sheep, which were lumbering in my direction. Id once had a narrow escape from a petting zoo where a sheep had tried to make a meal out of my pants, and I had no idea what twenty of them might do. Would sheep chase down and tackle a skinny man who tried to flee from them?

A facility employee waved as his truck scooted past, smilingI was sureat the idea that anyone would visit his workplace for fun. But the shorebird migration was in full swing, and I had hopes of finding a rare species. For reasons I didnt understand, sandpipers, plovers, and other waders gravitated toward sewage ponds on the way to their breeding grounds. My ability to tell those birds apart was virtually nonexistent. My only chance was shooting scads of photos and trying to identify them later by scouring three shorebird reference books, five general birding field guides, three iPad apps, and the Internet. So far I hadnt found any shorebirds at all. Just sheep.

Finding not just any bird but a rare bird of some kind in my little corner of West Michigan had been my obsession for about a decade. Id seen rarities passing through the area, from cattle egrets to greater white-fronted geese, but only because reports from the birders who had discovered them told me exactly where to look. I had yet to find a noteworthy species on my owna bird that other birders would want to see. Ferreting out a rare bird would indicate that I had finally arrived, achieving bona fide rather than bumbling birder status. It would jolt my sad-sack soul with a surge of happiness like a bibliophile discovering a Dead Sea Scroll at a rummage sale or a fossil hunter finding a whale vertebrate poking out of a backyard boulder.

But there was more to it than that. Throughout my life, Id always given up on any pursuit the instant that it turned into worklike playing a musical instrument more complicated than a pocket comb or making cute, blobby coffee cups on our potters wheel. The only skills Id mastered were dodging household chores and falling into a deathlike nap in the blink of an eye. By achieving a minimal degree of competency as a birder, I could prove to myself that I hadnt sputtered out a quarter of the way to every goal Id set for myself and that I wasnt, in fact, the laziest mammal on the planet. While Id never live long enough to evolve into an expert, I could finally say the words yellow-bellied sapsucker without sniggering and more or less knew what one looked like.

As I rounded the pond, the sheep changed direction and walked then trotted toward the back of the property. I was safe from depantsing for now. At the same time, three tiny sandpipers peep-peep-peeped and rocketed off, their pointy wingtips nearly brushing the water. I didnt have a clue what they were. They looked like every other sparrow-size sandpiper Id ever seen. Identifying a rarity required learning all of the common birds first, then the uncommon but not necessarily rare species next, and finally having at least a passing familiarity with the good-luck-seeing-any-of-these birds. The learning process seemed endless. The more I learned, the more I learned I didnt know. Hawks still looked alike to me. Sparrows merged into a streaky blur. Most thrushes and flycatchers needed to sing before I could pin a name on them, and the only shorebird I knew at a glance was the killdeer of ball field and parking lot fame.

My first rose-breasted grosbeak dumbfounded me by tricking out his tuxedo with a blazing red cravat.

Like a broken clock that wasnt even right twice a day because the hands had fallen off, I didnt have much chance of success. But I loved birds more than anything in the world, with the possible exception of my wife, Linda, and our cats. So even if I failed, there really wasnt a downside to doing what made me happy, other than the public humiliation of announcing yet another bogus identification to the online birding community and having to tearfully retract it. So I was determined to keep trying to find that rare bird that would change my life in a subtle yet meaningful way.

Next page