SONNY

LISTON

By the same author

Sportswatching

(with Steve Pinder)

Spring Summer Autumn Three Cricketers, One Summer

1993 Guide to County Cricket

Desmond Haynes Lion of Barbados

The Mavericks English Football When Flair Wore Flares

David Gower A Man Out of Time

Poms and Cobbers Ashes 1997 An Inside View

(with Robert Croft and Matthew Elliott)

Inside the Game Cricket

The New Ball Volumes 17

Official Companion to the 1999 Cricket World Cup

This Sporting Life Cricket

500-1 The Miracle of Headingley 81

(with Alastair McLellan)

Sports Journalism A Multimedia Primer

To my parents, John and Shirley,

and my first niece, Kate Emily

To my profound regret, Sonnys widow Geraldine, suspicious to the last, and forgivably so, declined my requests to participate in the making of this book. Happily, others were more co-operative, notably Davey Pearl, Henry Cooper, Floyd Patterson, Father Alois Stevens, Bill Cayton, Al Braverman, Bernard Poiry, Joey Curtis, Nino Valdes and, above all, Hank Kaplan, who offered visual as well as verbal memories. Ken Jones, William Nack, Colin Hart and David Field supplied invaluable leads, while Peter and Jane McInnes provided coffee, biscuits, endless bookshelves and unresolvable moral debates. And to Anne and Woody, heartfelt thanks for love, patience and encouragement.

I am grateful too for permission to reproduce the following photographs: Associated Press (nos 3, 7), Hulton-Deutsch (15), PA-Reuter Photos (17), Planet News (4, 5, 8, 16) and Topix (6). The remaining photographs and the chapter ends are from the Hank Kaplan collection and from Harry Mullan at Boxing News, whose practical help was greatly appreciated.

Most of all, I would like to express my gratitude to Tony Pocock and Neil Tunnicliffe at the Kingswood Press (now Methuen) for showing faith in someone whose only connection with boxing was a grandfather who used to act as ringside doctor at York Hall.

ROB STEEN

London

One

I was the king of the alley, mama

I could talk some trash

I was the prince of the paupers

Crowned downtown at the beggars bash

I was the pimps main prophet

I kept everything cool

Just a backstreet gambler with the luck to lose.

(Bruce Springsteen, Its Hard To Be A Saint In The City)

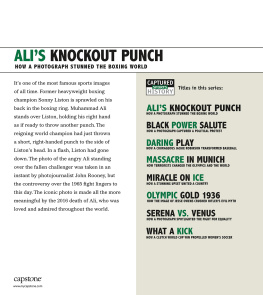

Emphasising the animal in us all, the most telling line in Woody Allens marvellously cerebral film Manhattan is Isaac Daviss suggestion that, in the unlikely event of Nazis invading New Jersey, the locals would be better off returning fire with baseball bats than biting satire. During the same movie, a woman reveals that the only orgasm she has ever experienced was the wrong kind. If Charles Sonny Liston had any luck at all he, too, had the wrong kind. Like Bruce Springsteens hard-pressed saint, he had the luck to lose. Shackled by chains of disadvantage that imprison most souls for life, he almost broke free. He was granted a second chance. Sadly, he was never really allowed to take it. The late Harold Conrad, who spent endless hours oiling Listons publicity machine, may have been overly melodramatic when he observed that Sonny died the day he was born, but only just. This was a man on whom fortune bestowed a wicked, teasing asp of a smile.

The heavyweight boxing champion of the world enjoys a status no other man can hope to match. He is the king of the alley and the prince of the paupers. He puts the ass into masculinity, the roar into terror. A two-legged billboard promoting the profitability of physical force. The Dean of the Mean. The champ stands alone, unable to delegate, unable to hide behind the strength and commitment of others. Tougher, frequently rougher than the rest, his very existence is wholly reliant on western civilisations rusty notion of what constitutes a Real Man. In his pomp, Sonny Liston was as real, as fearsome an hombre as ever pulled on a pair of gloves.

To say that the acquisition of such symbolic trappings is not without its drawbacks would be something of an understatement. There is the self-delusion: the belief that might can be right rather than trite, that muscle can lift you above the hustle. There is the envy and patronising of others, and the animosity which that brings; there are the principle-shorn pimps and bullshit artists who pick your pocket and peck away at your future, a future already shrouded in a blanket of bruises to body and brain. Few objects of fear are subjected to such ridicule. Few riflemen make such easy targets. It cannot be coincidental that boxing is the only sporting category in the Guinness Book of Records that includes a section listing, and by implication canonising, its oldest champions at the time of their death, which must say something (take a bow, Jack Sharkey, wherever you are).

True, the $35.8 million that Mike Tyson and Michael Spinks earned between them for ninety-one seconds work at the Atlantic City Convention Hall in 1988 would have fed more than 400,000 starving people for a year, inoculated around 10 million children against the six killer diseases, paid for nearly 400,000 cataract operations for blind people in the developing world and raised as much for Ethiopia as Live Aid. But, for every mansion and jacuzzi, there is a Don King lurking in a shadowy corner, hand outstretched, palm upturned with the self-righteousness of a tax collector but with none of the social benefits. At his side, more threatening still, stands that most insatiable and merciless of opponents, the male ego, the monster that drives a man so far through the pain barrier that he fails to acknowledge its presence until the damage is irreversible. As Norman Mailer once put it: No physical activity is as vain as boxing. A man gets into the ring to attract admiration. In no sport, therefore, can you be more humiliated.

It would be nice to think that civilisation has progressed to a stage where the pen really does strike deeper than the sword, but only a ratepayer from Cloud-cuckoo-land would lend the possibility any credence. That said, if sport has a purpose above distracting the proletariat and turning competition into something approaching art, it is to prove that, unlike the nasty, real world, talent, diligence and patience can overcome all; that perfection is a viable proposition. However, as Lord Taylor of Gryfe pointed out when proposing his ill-fated Boxing Bill at Westminster in 1991, the laughingly-dubbed noble art is alone in promoting intended violence. American football, rugby and motor racing may each claim more casualties in any given year but, despite the vengeful gleam frequently discernible in the eyes of prop forwards and tight ends, despite the daggers Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost glare and sometimes thrust at each other, the aim of the combatants is not to beat each others brains out, nor to shred each others features, nor to break each others bones.

In boxing, the raison dtre is to hurt your opponent and so sap his resistance. Nightmare on Elm Street? Childs play. The most horrific moment in cinematic history is that monochrome shot in Raging Bull of blood oozing from the ropes, every drip another ounce of humanity drained from the male soul. Forget all that twaddle about elegant right jabs, Fonteynesque footwork and tactical acumen: hunting aside, pugilism in its essence remains as primeval a pastime as man can ever have conferred respectability upon. After all, in what other cultural activity is the audiences greatest thrill achieved by seeing one man knock another senseless? What other source of disposable income taps so easily into the beast within and without? Lord Taylors reasoning seemed sound enough: We have long since abolished cock-fighting and dog-fighting. Why are we less sensitive to the greater problems of young men in the ring?