ALSO BY S TEPHEN T AYLOR

The Mighty Nimrod

A Life of Frederick Courteney Selous

Shakas Children

A History of the Zulu People

Livingstones Tribe

A Journey from Zanzibar to the Cape

CALIBANS

SHORE

The Wreck of the Grosvenor and the Strange Fate of Her Survivors

Stephen Taylor

W. W. Norton & Company

New York London

CONTENTS

es

For Kikki and Princess Tree, who came along

And Tom, who yet again kept me on the straight and narrow

PROLOGUE

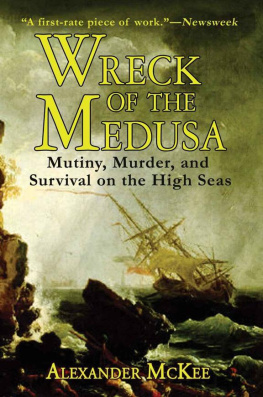

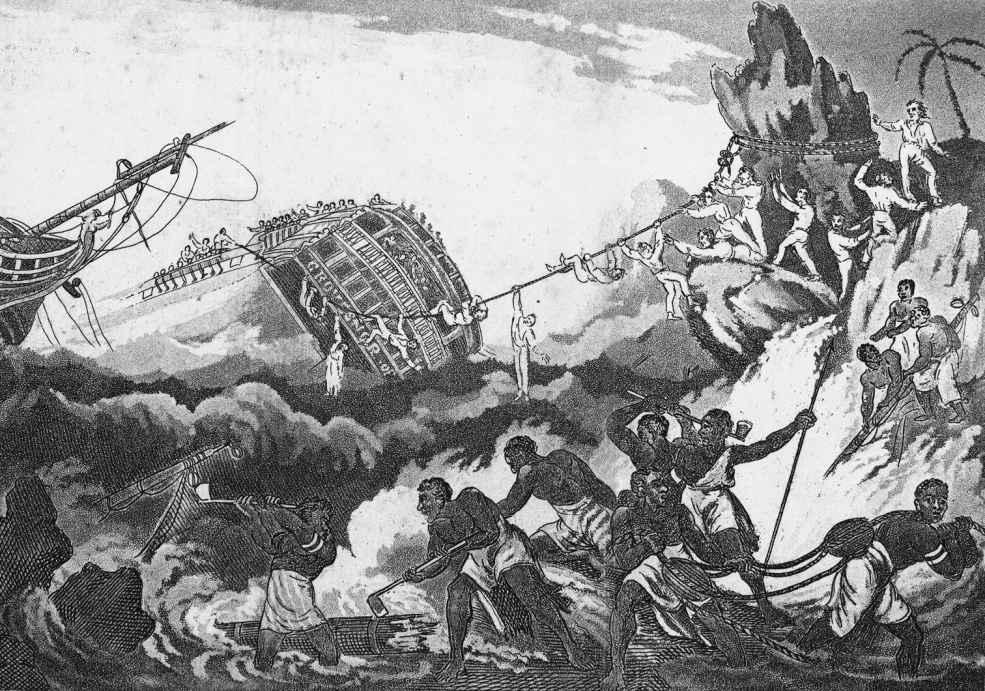

Indiaman in a storm between Madagascar and the Cape of Good Hope, from an etching of 1804

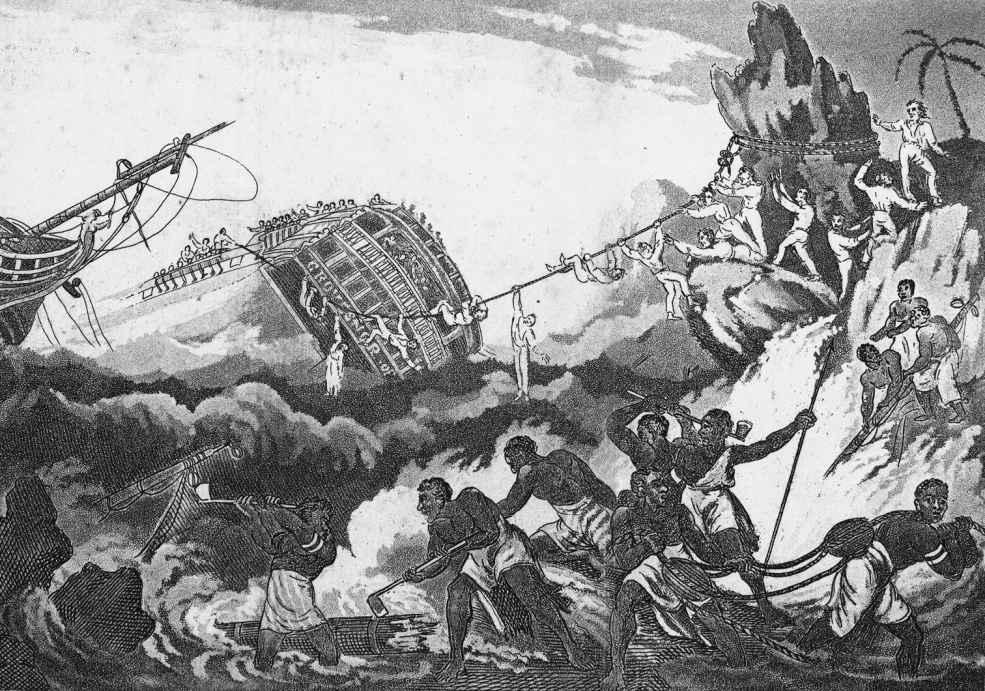

T he ship doubled the Cape of Good Hope on a cool July day with a brisk following wind and a film of moisture in the air that shrouded the first sight of land for seven weeks. She was an East Indiaman of 499 tons, outward bound for Madras on what promised to be the smoothest of her three voyages so far. Evan Jones, the chief mate, was moved to remark on a very pleasant passage across the Atlantic and few others on board could recall so calm or swift a crossing. Only seventy-five days had passed since the Indiamans departure from the Downs, the protected anchorage off the Kent coast, early in the spring of 1755, and she had long since left an accompanying squadron in her wake.

The weather turned almost as soon as they rounded the Cape. Jones described it as dirty and squally with the Wind from SSW to SSE and a very large sea and orders were given to haul in the staysails and shorten the main in order to reduce the amount of canvas exposed to a constant gale. Captain James Samson held his course due east for the next twenty-four hours. Like any experienced skipper of an East India Company merchant vessel, he was keenly aware that he had just entered the most dangerous part of the voyage, even if he understood no better than anyone else what caused the freak conditions that made south-east Africa notorious among mariners. When, the following day, Cape Agulhas was sighted, he set a new course East-North-East. The ship was now driving directly into the warm-water current, also called the Agulhas, which pulses invisibly along the coast.

Even with the staysails stowed and the fore topsails and the main closely reefed, the Indiaman was running along at between six and seven knots. Over the next eight days she churned headlong through squalls, until on 16 July the gale strengthened further and Captain Samson was obliged to order that still more canvas be hauled in. At noon that day they had reached a longitude of 13 45e of Cape Agulhas or so Jones, the chief mate, reckoned.

At a quarter to one the following morning, a forward lookout shouted down from his post, Breakers ahead and to leeward! Jones described what followed: The helm was immediately put a-lee; but before she came quite Head to Wind, she struck lightly and then stronger.

William Webb, the third mate, was asleep in his cot when the first shudder went through the ship. Instantly awake, he clambered down, to feel a series of vibrations under his feet, followed by a jolt that tossed him from one end of the tiny cabin to the other. Further shocks marked his scrambled passage up the companion ladder.

By the time Webb reached the quarterdeck, all three masts were gone. In their place a mountain of canvas and rigging billowed across the deck. Water swirled at his feet and he watched in a dreamlike state as a wave broke over the side, catching up a dozen or so men in its midst and carrying them off into the darkness. Within minutes of impact with whatever she had struck, a ship as solid as the forest of oaks from which she was hewn had started to break up.

So brutally brief was the crisis that not one of the hands had an opportunity to break into the liquor barrels and drink himself into the merciful oblivion sought by seamen facing certain death. Most of them died below decks or in the cataclysmic break-up of the hull. So did the great majority of a company of Royal Artillery troops who were sharing the crews quarters.

What saved some of the ships officers was the location of their cabins in the stern. Jones, the chief mate, emerged from his quarters around the same time as Webb, to find the Indiaman starting to disintegrate. By the time I got upon deck it was falling in and other parts driving to peices [ sic ] faster than any person can imagine, he wrote. Somewhere in the inkiness he found Captain Samson and asked him where he thought we were, for I own the mainland never enterd into my head. Nor the captains neither, for the answer he made me was it must be some rock in the sea which never was laid down.

Jones estimated that at one point about thirty men were clustered on the quarterdeck, but each time a wave broke it carried more of them away into eternity on a tide of foam. Samson bade him farewell, and said we should meet in the Next World, which words were scarce out his of his mouth, when I was washd off.

Webb, meanwhile, had been clawing his way up towards the larboard side of the quarterdeck, crazily angled above the water, where he found Samson alone. The captain had a dazed appearance and managed to get out little more than that they were doomed, before the sea crashed over them. The last Webb ever saw of him was as he disappeared over the side.

No longer certain even of what portion of the ship he was on, the third mate was awaiting the inevitable when out of the darkness a voice cried, Land! At first, looking over the breakers, he took the black mass ahead to be colossal seas, and had no chance to reconsider before a wave crashed over him and he lost consciousness. He awoke at daylight, numb with cold, his right arm broken, and impaled by the shoulder on a nail protruding from a beam. By pure good fortune he had been left face up in shallow water and, having thus escaped drowning, was able to disengage his shoulder from the wreckage and crawl to shore.

Out of the 270 souls who had been on the Dodington for that was the East Indiamans name Webb was one of just twenty-three to have been spared. Others included Jones, who had also been deposited on the shore, John Collett, the second mate (but not his wife, whose body was found washed up nearby), Richard Topping, the carpenter, ten sailors and three out of the ninety-five soldiers. They found themselves stranded on an uninhabited island, barely six miles from the mainland at the eastern end of Algoa Bay. How this band of castaways endured on Bird Island for seven months while they fashioned from the wreckage a sloop that they called the Happy Deliverance their adventures, quarrels and feuds, and their eventual voyage in this makeshift vessel to Madagascar and safety is itself a great survival story.

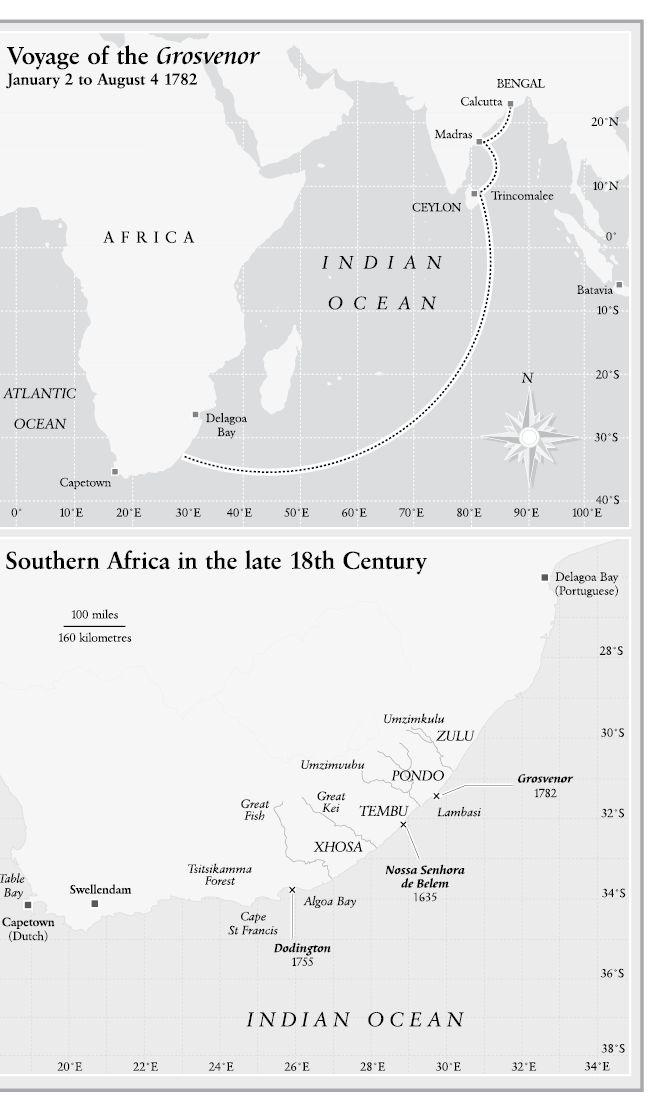

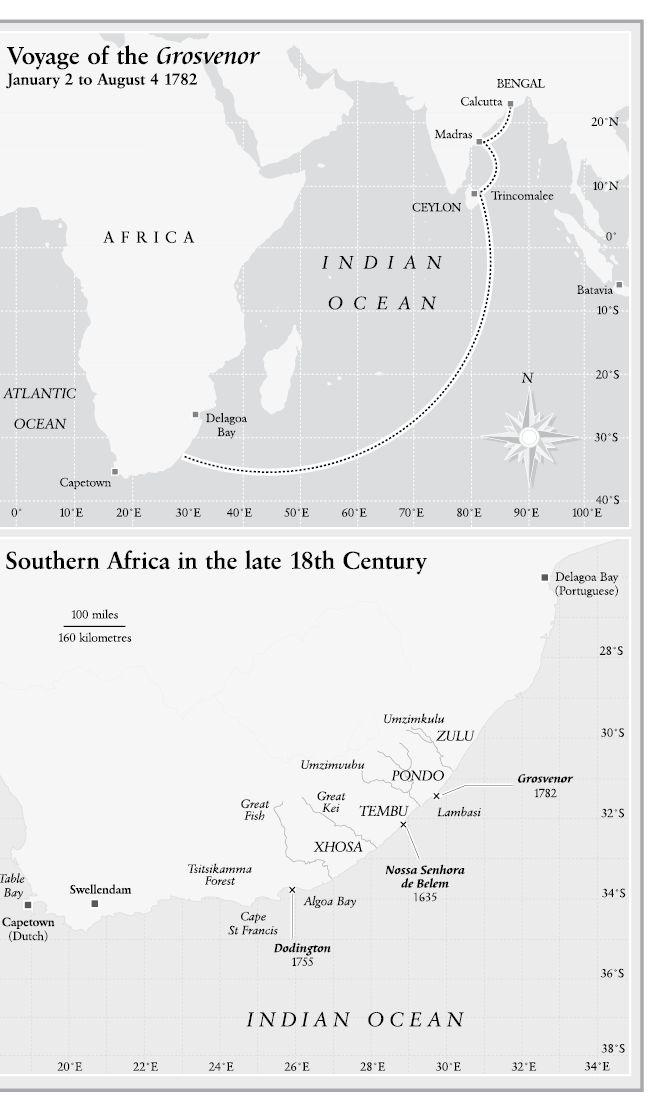

The Dodington disaster echoed from London to Bengal. As well as troops for Robert Clives latest campaign to drive the French from India, the East Indiaman had been carrying military hardware and bullion; Clive, indeed, had intended taking passage on the Dodington himself and had only switched to the Stretham at the last moment. Navigational experts were summoned to consider this shocking circumstance and how to avoid any repetition of it. Already there was a strong suspicion that British maps, based on the Portuguese Roteiro chart drawn up almost two centuries earlier, were lethally flawed in showing the coast of south-east Africa some degrees west of its true position. Fundamentally, however, the wreck was found to have been a consequence of the very erroneous reckoning of the ships position. Whereas the chief mate Jones had calculated it as 13 45e of Cape Agulhas, later observations had found it to be no more than 7e. The Dodington had been set on too northerly a course too early.

Next page