Actor, writer and broadcaster Michael Veitch began his career in television comedy programs before freelancing as a columnist and arts reviewer for newspapers and magazines. For four years he presented Sunday Arts, the national arts show on ABC television, and has broadcast regularly across Australia on ABC radio. He has produced two books indulging his life-long interest in the aircraft and airmen of the Second World War, Flak and Fly as well as The Forgotten Islands in which he explores the little-known islands of Bass Strait. In 2015, he began touring a one-man stage version of Flak nationally.

whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

POST SCRIPT

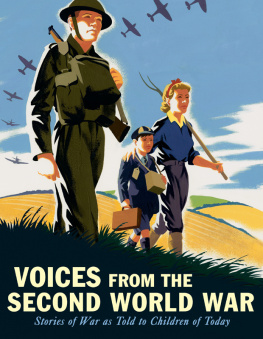

I still recall sitting down for my very first interview with an airman, in his living room in a leafy suburb in my home city of Melbourne. I was aged about thirteen. I had no idea it was going to be an interview at the time of course, but thats what it turned out to be. The man I had come to see was Arnold Easton, a former 467 Squadron navigator who had completed a full tour of operations on Lancasters during a period of horrendous losses for Bomber Command in 1943 and 1944. Arnold was a tall man, and striking, with pale, intelligent blue eyes and remains still in my memory as one of the quietest and most gentle men I have ever met. It occurred to me only recently, as I completed the final interview in this book, that Arnold would have then been, in the mid-1970s, roughly the same age I am now, somewhere in his early fifties.

Wed met by chance through a friend of my mothers at a theatre function to which I was reluctantly dragged, but towards the end of the evening, the two of us struck up a brief conversation about his wartime flying. How the subject ever came up I have no idea. My parents, long inured to my obsession, no doubt rolled their eyes and left us to it. A week later, I presented myself at his doorstep, having accepted his invitation to talk further.

He was prepared for my visit, as his niece had recently completed a school project on her quiet airman uncle, and he had it out ready to show me. He probably thought our discussion would be similar to the one he had recently conducted with his niece: answering some general questions, explaining some technicalities, and giving a generalised overview of the great air war in which he had participated. But he was wrong. The school project was spread across a dining room table on several sheets of fine white cardboard, covered with tidy, spidery writing and cut out pictures of aeroplanes, annotated diagrams and tables of figures. As soon as I saw it, I was drawn instead to a small bunch of shiny metallic strips sticky taped to a corner. Now I just want to tell you what this is, he began, but before he could finish the sentence I simply said, window, recognising instantly the aluminium foil strips dropped by the ton by the bombers to confuse German radar. He stopped and looked at me anew. How did you know that? I shrugged my shoulders like a typical thirteen-year-old.

For some reason, Arnold ended up telling me more that day than hed ever considered telling his niece. For me, it was a revelation, the first proper conversation with someone who had lived an obsession which, even then, I had carried in my head for years. Navigators were special. Highly intelligent, meticulous, sensitive. The brains of the aircraft, as many of their grateful crew described them. Their responsibility in guiding their bomber across a hostile, blacked-out continent to a pinpoint target and back again, using nothing but a map, a wristwatch and mental arithmetic was almost incomprehensible. I kept asking Arnold questions, endless questions. Some he ignored, or skirted around, so I would ask him again. I made him describe to me all he could remember about the Lancaster, the colour of its interior, and its smell. I forced him to recall faces, conversations, voices. We spoke about aeroplanes, the art of navigation, the men he knew and the base, at Waddington in Lincolnshire where he was stationed. The strangest thing was flying into a battle, with aircraft going down around you, flak exploding, thinking every second you were about to die, then coming back and waking up in clean sheets in the middle of the English countryside with rabbits darting in and out of the hedgerows, he said.

As he spoke, the quieter and the paler he became. Gradually I stopped asking, and just listened. Regrettably, I have now forgotten much of what he said, and in the end my presence was an irrelevance anyway. His eyes fixed on the centre of a table, he began, unprompted, to speak about the wrenching, unbearable stress of his tour, of watching faces he knew around him gradually disappear, and the nightmares that visited him still. He thought, he told me, about the bombing itself, about what was happening on the ground, underneath his Lancaster, as tons of high explosives cascaded onto factories, houses, hospitals, apartment blocks, God knows what.

He showed me his Distinguished Flying Cross, still in its case, its liquid, silver arms fashioned poetically to resemble propeller blades under a ribbon of diagonal blue and white stripes. He was proud of it, but I remember also an awkwardness, as if he himself didnt quite know what to make of it. I remember wanting to take it out of the box and handle it, but he said something and closed the lid, returning it to its home in the bottom drawer of a desk.

He then passed me an old blue cloth-bound book with a small RAF wing and crown embossed on the cover. Air Navigation, Vol 1, said the title, and on the inside cover His Majestys Stationery Office, 1941. For Official Use. Its pages were creamy and smooth and filled with myriad intricate, diagrams, charts and tables. Its chapter headings included, The Theory of Dead Reckoning Navigation, Astronomical Navigation and Wireless Direction Finding. This was, Arnold told me, his navigators text book, the bible from which all navigators learned the craft of getting an aeroplane from A to B. I was taken with it immediately and began asking him to explain some of the details, many of which he could still recall without hesitation, while others had been long forgotten. Something then tripped me up, a quote at the beginning of the first chapter, not, as one might expect from the king or some figure of influence concerning duty or responsibility, the first words young navigators read were, bizarrely, those of Lewis Carroll:

Of course the first thing to do was to make a grand survey of the country she was going to travel through. Its something very like learning Geography, thought Alice.

Alice Through the Looking Glass

Hang on to that if you like, Arnold told me, and I did.