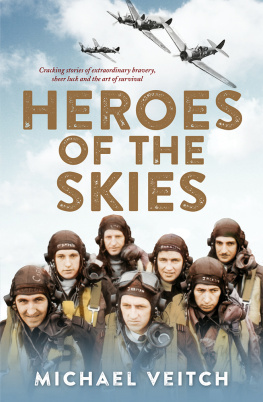

Michael Veitch comes from a family of journalists, and although known mainly as a performer in television and theatre, has contributed to newspapers and publications for a number of years. He has had a lifelong interest in aviation, particularly during the Second World War, and studied history at the University of Melbourne. He lives and works in Melbourne and is currently the host of Sunday Arts on ABC television.

FLAK

True stories from the men who flew in World War Two

MICHAEL VEITCH

First published 2006 in Macmillan by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Limited

1 Market Street, Sydney

Copyright Michael Veitch 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

National Library of Australia cataloguing-in-publication data:

Veitch, Michael.

Flak : true stories from the men who flew in World War Two.

ISBN 978 1 40503 721 1 (pbk).

ISBN 1 40503721 0 (pbk).

1. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force - Airmen. 2. World War, 1939-1945 - Aerial operations, Australian. 3. World War, 1939-1945 - Personal narratives, Australian. I. Title.

940.544994

Every endeavour has been made to contact copyright holders to obtain the necessary permission for use of copyright material in this book. Any person who may have been inadvertently overlooked should contact the publisher.

Cover images from the Australian War Memorial, Negative Number UK0960 and the Argus Newspaper Collection of Photography, State Library of Victoria.

Typeset in 12.5/16 pt Sabon by Midland Typesetters, Australia Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

Papers used by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

These electronic editions published in 2008 by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd

1 Market Street, Sydney 2000

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. This publication (or any part of it) may not be reproduced or transmitted, copied, stored, distributed or otherwise made available by any person or entity (including Google, Amazon or similar organisations), in any form (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical) or by any means (photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

FLAK

MICHAEL VEITCH

Adobe eReader format 978-1-74197-158-3

Microsoft Reader format 978-1-74197-359-4

Mobipocket format 978-1-74197-560-4

Online format 978-1-74197-761-5

Epub format 978-1-74262-599-7

Macmillan Digital Australia

www.macmillandigital.com.au

Visit www.panmacmillan.com.au to read more about all our books and to buy both print and ebooks online. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events.

To the ones I never met.

Foreword

Michael Veitch has done a fine job of getting those of us who were shot at a lot in the skies of World War II to talk about things we seldom discussed in great detail anywhere. Though I had many friends in heavy bombers I was never in one myself. My Mosquito navigator had been shot down on his first tour in a Beaufighter then came to me. I had friends on long range Coastal Command aircraft, on medium bombers, on fighter squadrons and low-level ground attack. Not many survived.

The accurate descriptions in this book taught me so much, almost for the first time. I may have been frightened on several occasions in my job as a photographic reconnaissance pilot but I have often wondered if I could have done what other air crews had to do. That any of us survived at all, regardless of what our duties were, is sometimes hard to believe. Thank you, Michael, for illuminating so much about so many.

Charles Bud Tingwell, 2006

Introduction

An Obsession

Inside the head of every pilot, navigator or gunner who flew during the Second World War is at least one extraordinary story.

One of the best I heard was from a bloke I never got to meet. He was a rear-gunner in a Lancaster bomber and as such, sat away from his six fellow crew members at the back of the plane, shut inside a tiny perspex and aluminium cage right under the tail. A hydraulic motor powered by a relay in one of the bombers four engines allowed him to swivel back and forth through slightly more than 90 degrees while the four mounted machine guns tracked vertically, protruding rearwards through the turret, controlled by a small hand grip. The trick was to coordinate the sideways movement of the turret with the vertical movement of the guns and bead in on a moving target, usually an enemy night fighter, in an instant. In 1943 this was brilliant technology. Indeed, the aircraft itself symbolised the absolute upper limit of what was achievable both technologically and industrially at the time, and required a massive some have argued disproportionate investment of Britains wartime resources.

Inside the turret there was virtually no room, not even for the gunners parachute, which had to be stowed on a shelf inside the fuselage and separated from the turret itself. So, if the moment came to jump, he would need to open the two small rear doors, climb back into the fuselage, locate the chute, strap it on, then make his way forward and leave the aircraft via the main door, presumably while being thrown about as the mortally wounded aeroplane went into its death spin from 20,000 feet. Easier said than done.

As the story goes, this fellow was directly over the target on a big night raid into Germany, his aircraft right above one of the large doomed cities being systematically wrecked by fleets of up to a thousand RAF heavy bombers at night, and possibly the Americans by day. Peering into the black sky, he swept his guns up and down, back and forth, watching for enemy fighters. Some of them reckoned that by just looking busy you appeared more alert to the German pilots and were less likely to be attacked. Suddenly he saw something a dark shape moving fast possibly another bomber, possibly a German night fighter passing underneath. As he leaned forward over his guns to gain a better view he felt two mighty almost instantaneous bangs and something slither quickly down his back. The turret instantly stopped working, making the guns inoperable, but both he and the aircraft seemed otherwise undamaged. He looked up. Inches above his head he saw a baseball sized hole in the top of the turret and underneath it, a matching one in the floor. It took only a moment for him to work out what had happened. An incendiary bomb a small aluminium pipe crammed with magnesium and dropped in their hundreds had fallen from another bomber above and passed clean through the turret before continuing on its way.

At night, with inexperienced pilots and up to a thousand four-engined aircraft passing over the same target in roughly 20 minutes, being bombed by your own side, not to mention mid-air collisions, were just a couple of the occupational hazards of flying with Bomber Command during the Second World War. Were it not for the fact that this fellow just happened, in that very instant, to be looking out for something he wasnt even sure was there, he would have certainly been killed. As it was, his turret was useless and he could only hope a night fighter didnt decide to pick on him on the way home. This night he was lucky.

Next page