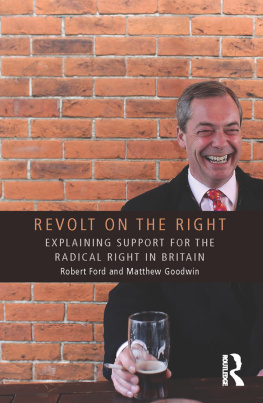

N igel Farage is one of the most outspoken and controversial politicians ever to grace the British political stage. Not since Enoch Powell has one mans radical language and provocative humour garnered so much attention and, indeed, derision.

Loved and hated in equal measure, Farage has undoubtedly been the thrust behind the rise of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), which is currently on the cusp of breaking the British political mould. The partys stunning electoral triumph in the 2014 European elections in which they polled first would have been impossible without Farages voracious leadership. And his success has only grown since, with two UKIP MPs now sitting in the House of Commons and a real chance of Farage and other UKIP candidates joining them later this year (2015).

Farage has made the party of fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists, as David Cameron described them, a household name. And nothing has made him more popular or, perhaps, well known than his outspoken antics. Witty, biting, cutting and outrageous, often all at once, Farage has positioned himself as a lone splash of colour in an era of monotone political leaders. He deliberately shuns political correctness, which has led some to reject him as racist and xenophobic, but at least as many to respect him. His words have helped define him as someone who is viewed despite being a public-school-educated, ex-City trader as unlike other politicians.

Clad in his trademark Barbour, fag in one hand, pint in the other, Farage has undoubtedly succeeded in making people believe he is like them, and, perhaps even more importantly, speaks for them.

Yet it has not always been this way. Farage excluding a brief hiatus in 2009 has been leader of his party since 2006, and, until recently, has hardly electrified the nation. In 2009, UKIP would gain 15 per cent of votes in the European elections but in 2010 they would receive just over 3 per cent of the vote nationally.

And, despite recent by-election triumphs, the historical precedent for an insurgent party breaking the mould of British politics is patchy at best. The Social Democratic Party (SDP), founded in 1981, won several by-elections and garnered 26 per cent of the vote nationally in 1983, but would actually end up losing seats in our first-past-the-post electoral system. Led by veteran big beast Roy Jenkins who, apart from smoking and drinking, was little like Farage the SDP promised a great deal, but ultimately failed to unseat the two main parties from the dinner table of political power.

On the other hand, there is the example of the Scottish National Party in Scotland, who, like UKIP, have focused more on populism than cold policy. From 1992, Alex Salmond who is similar to Farage in many ways began a strategy that would create a dangerous, new and influential force outside the political mainstream. Whether Farage is more of a Salmond than a Jenkins, only time will tell.

Of course, like any modern-day politician, Farage has endured his share of controversy and scandal: an alleged liaison with a 25-year-old Latvian he met in a pub; outrageous expenses claims; and, of course, colourful language on immigration. Comments, for instance, that he felt uncomfortable on a train in which no one in his carriage was speaking English, led to widespread derision in the liberal media, particularly given he is married to a German.

But, as open borders and the free movement of labour have grown into the public consciousness, so Farage has become more popular. He has positioned himself as someone outwith the Westminster cabal someone who speaks his mind and, some would say, the mind of the British people. Any scandal that he or more often his party members are involved in has failed to put the brakes on the UKIP express train.

If anything, they have made him stand out, like a British Berlusconi. He has appeared in adverts; he has survived cancer, a plane crash and being hit by a car; he is, at the very least, exceptionally lucky.

Anything that hits the Teflon-like Farage, he can inevitably turn into a vote-winner.

Speaking everywhere from the hallowed chambers of the European Parliament to the pubs of middle England, Farages biting attacks have won him friends and enemies in equal measure. His wicked wit has delighted the growing group of voters disaffected with the UKs three main political parties. His words, as the country approaches the general election later this year, mean that UKIP are posed to potentially deal a deathblow to the Westminster mould.

Whatever their success, there is little doubt that Farage his words, wisdom and wickedness have been the central driving force behind the partys meteoric rise.

Never one to shy away from controversy, this book brings together some of the quotes that have made Farage the political phenomenon he is, as well as the responses they have generated. And, in doing so, it provides a snapshot of one mans journey to the pinnacle of political populism.

N igel Paul Farage was born on 3 April 1964 in Kent. His father, Guy Oscar Justus Farage, was an alcoholic stockbroker who walked out on the family when Nigel was five years old.

Farage attended the public school Dulwich College. Here he grew to love the classic sports rugby and cricket and, one teacher suggests, fascism.

Reaching the age of eighteen, Farage rejected further education at university, choosing instead to follow in his fathers footsteps in a career as a broker in the City. He traded on the metals exchange where he enjoyed the hard-living atmosphere prevalent in the financial services.

After a night in the pub, the young trader was run over by a car. His injuries were so severe doctors thought he might lose a leg. Grainne Hayes, his nurse, would become his first wife. He would go on to have two sons with Ms Hayes and a further two daughters with his second wife, a German called Kirsten Mehr.

Shortly after recovering from his crash, he was diagnosed with testicular cancer. He came through the experience increasingly determined to make something of his life.

Farage enjoyed moderate success in the City, but his work also helped him develop a more refined political consciousness. A traditional Conservative, he became disillusioned with the party under John Major, particularly after the former premier signed the Maastricht Treaty.

Farage was one of the founding members of the Anti-Federalist League, which would eventually grow into UKIP. At the 1997 general election, the burgeoning party was overshadowed by the Referendum Party. Despite being backed by multimillionaire businessman Sir James Goldsmith, it soon faded, with UKIP picking up much of its anti-EU support.

In 1999 and largely thanks to the proportional representation system used at European elections UKIP made its first breakthrough. Farage was elected to represent the south east of England one of three UKIP members voted to represent their constituents at the European Parliament.

In 2004, Farage successfully recruited TV presenter and ex-Labour MP Robert Kilroy-Silk to be a candidate in the European elections that year. He was elected alongside a re-elected Farage and ten other UKIP MEPs but then attempted to take the party over, before scuttling off to found the short-lived Veritas Party.

In 2006, Farage replaced the less charismatic Roger Knapman as UKIP leader.

Under Farages helm, the party raised its profile and, in the 2009 European elections, got more votes than Labour and the Liberal Democrats. That year, Farage also resigned as leader to take on House of Commons Speaker John Bercow in his Buckingham seat.

He crashed an aircraft on election day in 2010 and came third, behind Mr Bercow and a local independent candidate. Farage returned to the leadership of his party later that year.