Contents

Guide

THE PULL OF

THE RIVER

For Jen, Seth and Eliza

Contents

Prologue

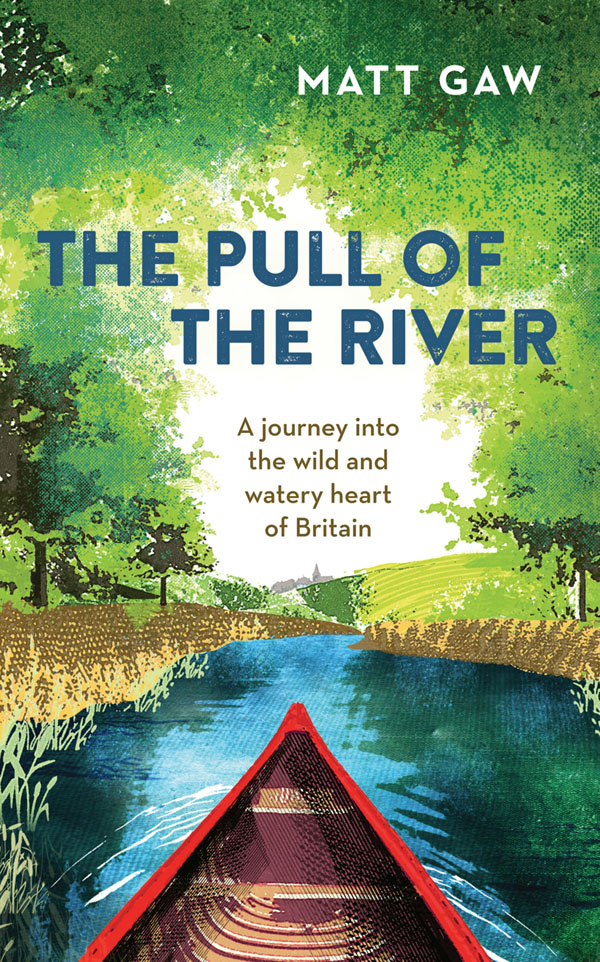

T his is just a wet run, a jaunt to celebrate the building of the canoe, but Im already lost to the water: the way she holds us, the gentle current squeezing us downstream like muscles inside the throat of some giant snake. The river here is wide and soft, bobbled and furred with a yellow fuzz of catkins blown from groups of willow that lower their tresses to the water like women washing their hair. We are moving slowly, each paddle stroke sending up tiny green whirlpools that dance and wink in the summer evenings light. Behind us we leave a wobbling trail of water, folding in on itself and disappearing with just the smallest of bow waves that shiver to the muddy bank.

The pair of us my friend James Treadaway and I set out just under an hour ago from Sudbury Water Meadows, humping the Canadian canoe past the last of the picnickers and the first of the cider drinkers. We heaved her into position and slid her nose-first into the water, wincing at the sound of her wooden hull scraping along the platform and sighing with relief when she didnt sink to the rivers silty bottom. It was James who built this canoe. A suburban Noah, he beavered away in his garden while his bemused neighbours peered over the fence, offering encouragement and the odd glass of orange squash. Like me, he has little experience of being on the water, but said he felt compelled to make a boat; spending months bending, shaping and gluing wood, before painting the canoes handsome curves and broad bottom a joyous nautical red the colour of Mae Wests lips.

The canoe is high in the water and reassuringly stable, but it took until the frothing flow of Cornard Weir for us to learn how to keep her steady, our rookie strokes pulling and pushing the canoes nose from bank to bank like a swinging compass needle. Once, twice, three times we ploughed at speed into the side or plunged through thrashing branches and into reeds, emerging sheepish and covered with downy seeds and a boatload of surprised insects. The rhythm is easy now, the lifting and the pulling of the paddles unthinking and unhurried, minds and boat adrift.

In front of me James gestures with his hand. He doesnt need to say anything. Both of us have grown up near this river. Played on its banks, shinned up its trees and cooled off in its waters, but this is the first time we have actually stepped off the land and followed it; have felt its pull; its relentless crawl to the sea. In some ways its a strange feeling. I had it as soon as we pushed off, not so much an out-of-body experience as an out-of-land experience. Yet thats not right either, because Ive never felt so utterly consumed and engaged with a landscape. I feel like I have been ushered into a world that until now has somehow been hidden. It is as if the river is a vein beneath the skin of the land and has the power to take us into the wild and watery heart of things.

We stop paddling, listening to the trickle-slap, trickle-slap of water on wood. A kingfisher darts overhead in a flash of azure, his shrill ch-reee joining the rivers quiet song. I hadnt thought about the smells of the river too. This isnt the fierce salt of the sea or the cabbage tang of seaweed, but the delicate, changing scents from wood and water. It is soothing beyond belief.

The trees start to thin out, making way for farmland, and we are joined by a barn owl, following the course of the river banks on her evening hunt. I watch her between strokes. Shes delightfully top-heavy, a feathered wedge, like a cartoon body builder. I remember how surprised I was when I first held one, by its lightness, the fragility of its air-filled bones. She has gone by the time we meet a woman standing on a paddle board next to the left bank. We drift past and chat, impressed by her skill and speed on the water, our progress clumsy in comparison. The pub she tells us is just five minutes away.

At the Henny Swan we pull the canoe out of the water and upend her by the bank, ordering pints and chips and then eating them by the river. The beer garden is busy, mostly with couples dressed up for a Friday night out in Essex. I feel slightly out of place, puffed up with a life jacket and legs emerald-green with duckweed. James and I talk about the last hour and plot our next trip. We could go overnight. We could follow the river till it scents the sea. We could explore the waterways around where we grew up. We could cross the Channel. The list of possibilities is endless and exciting. A world that just an hour ago felt so utterly explored has cracked wide open.

We make good time back to the Water Meadows, the beer acting as cheery ballast, heaving the canoe onto the bank to watch a teenager spinning for pike. It is a week before the river season begins and he seems nervous about being observed. His cigarette gives off a jazzy fug that suggests pike-poaching isnt his only naughty habit. Within minutes, a patch of water by a lily pad explodes and a great green fish leaps, flumping onto its belly with a crack that sends moorhens hiccupping away in alarm. The rod bends dramatically as the fish torpedoes off, heading for the cover of weeds and then... and then nothing. Slack line floats in the warm air like a gossamer thread. The pike has spat the hook.

Fucking hell! Did you see that? The boy asks, turning to look at us for the first time, his roll-up hanging from his lip, his face pale and his dark eyes wide under a baseball cap. We smile and nod. Like the pike, our minds are set on returning to the water.

Back home I feel restless and excited. I cant settle to anything. I pull out a stack of maps and look at the vascular bundle of rivers and tributaries spreading out across the county. I know many of the place names which the blue lines skirt round or slice through, but now and it feels like for the first time I can also see the miles of landscape, or rather the waterscape, I have missed. I trace them with my fingers and say their names out loud. The Little Ouse, the Waveney, the Stour, the Alde, the Orwell, the Box and the Rat. The Deben, the Dove, the Blyth, the Brett. The Kennett and the Yox. Then theres the Lark, the river that winds its way slowly through where I live now, in Bury St Edmunds. I move my finger down and find the Colne, welling up near Great Yeldham and striking out for my childhood home of Halstead. A river that is as homely as it is mysterious. A flow that has poured into my life, shaping me as surely as the mud of its meandering banks. But its route and the wildlife it contains were things I never really thought of. Although the river runs for 60 miles or more, for me, framed by my blinkered consciousness, it might as well have been just been a matter of yards. I feel now that I was missing the very things which made it special. Whats more, the same is true of nearly every river I have experienced. If these blue ribbons were a national park I would have barely pulled into the car park.

A plan begins to form in my mind. I will attempt to explore the country again by canoe first my country, the places I thought until so recently I knew so well; to rewrite a psychogeography made mean and narrow by the habits of land. But also I want to go further, to paddle along the great rivers that have inspired, moved and licked the land into shape. Places where it is still possible to get lost while knowing exactly where you are. It will be a quiet exploration of the UK, from the smallest tributaries to stent-straight canals and thick arteries that pump towards the sea. Over chalk, gravel, clay and mud. Through fields, woodland, villages, towns and cities to experience places that might otherwise go unnoticed and perhaps unloved. Not only that, but many rivers are also borders. While being on a river is sensually different, lowering us wet-bottomed into an eddying world of green water, it strikes me that it is also a place of freedom. A no mans land between counties and countries, where it is possible to stray briefly outside society, the only law being the pull of paddle against the current. Onwards. Onwards.