Translation Michael A. H. Newth 2014 All rights reserved . Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner The right of Michael A. H. Newth to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 First published 2014 D.S.

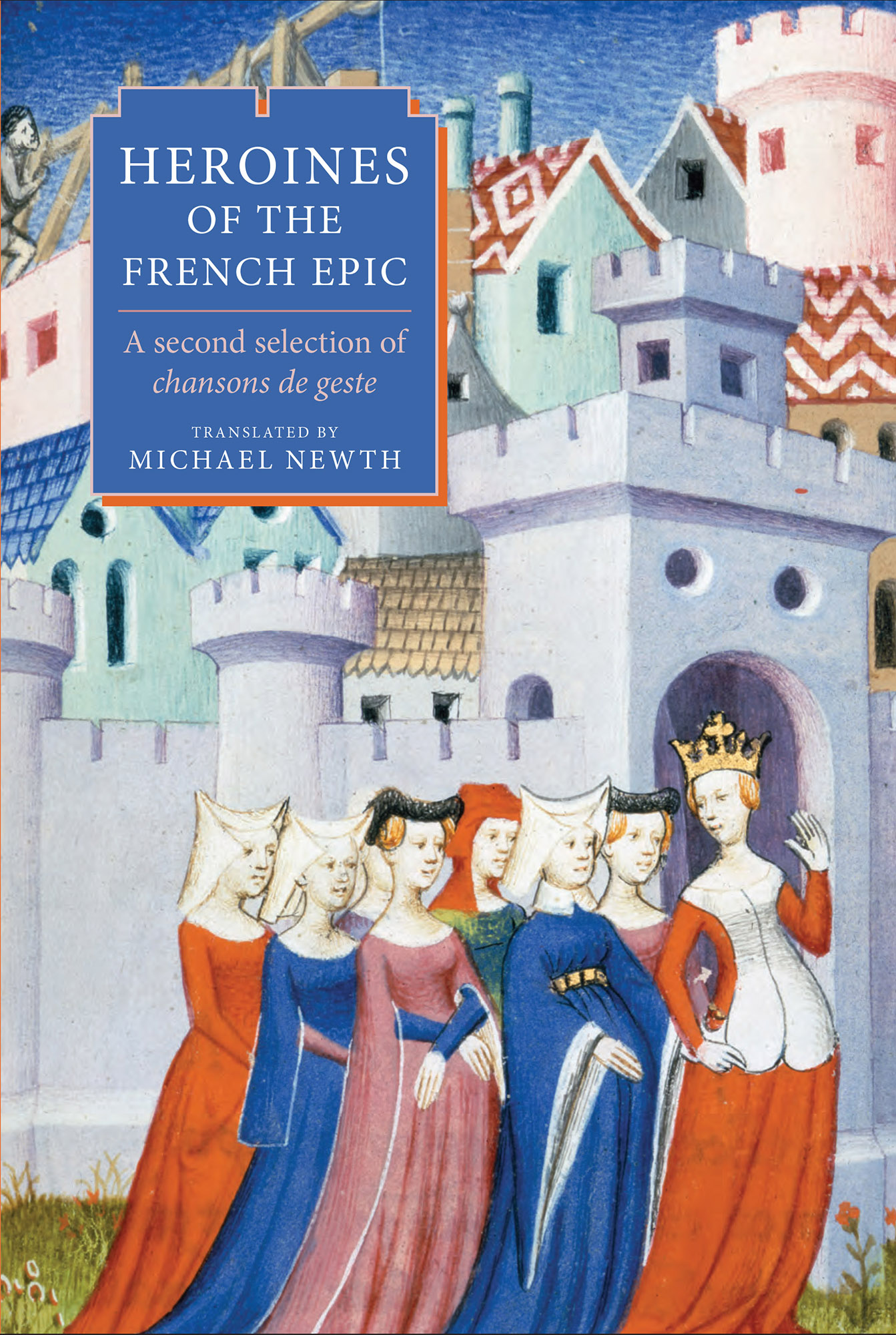

Brewer Cambridge ISBN 978 1 84384 361 0 (Hardback) ISBN 978 1 78204 285 3 (eBook) D.S. Brewer is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk, IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mount Hope Ave, Rochester, NY 146202731, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The publisher has no responsibility for the continued existence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. For Sue, my heroine Introduction In no period of French literature, neither in the romans daventure , nor in the society literature of the grand sicle , nor in the emancipated treatment of the modern novelists, is woman more attractively and more truthfully, albeit often navely, portrayed than in the chansons de . William Wistar Comfort (p.105) The chansons de genre to which modern English-speaking students or general readers are usually exposed and even then, again most probably, only through specially selected passages. As one critic has aptly said, such modern readers of the Song of Roland must be led to conclude that women are unimportant or even non-existent in the French epic(Harrison, p.672).

Indeed, the only two female characters in this 4,000 line poem (featuring well over one hundred named warriors) are the Saracen kings wife Bramimond, who is mentioned in four episodes totalling 147 lines, and Rolands fiance Aude, who is mentioned in only twenty nine lines, and speaks in only five of them. Both quantitatively and qualitatively Aude and Bramimond in the Song of Roland demonstrate, to the different degrees of their status as maid/fiance and wife/queen respectively, the subordinate and supportive role to which early medieval society, and hence its imaginative representations, had relegated them. For the aristocratic male audiences who listened to these epic tales in the eleventh century, men for whom national or ic duties were of the supreme interest, men who had consecrated themselves above all to national and religious service (Hindley & Levy, p.79), it was warfare and its associated moral and physical virtues that were of most importance and interest in life the pursuit of individual or clan honour, not that of amorous adventure. Thus in the earliest songs of deeds women figure very much as minor characters whose honour, like their status in society, is dependent on and reflected from males. Although the physical beauty of these early heroines is assumed, even regularly stated, it is not emphasised, and never the sole motivation for the taking up of arms. It is rather the mental and moral strengths of a woman her wit, intelligence, constancy, diligence, practicality, and powers of will and endurance, attributes that would make her a fitting companion for the epic hero (Herman, p.214), that ornament the earliest preserved songs, such as Roland and the Song of William , and remain an admirable feature of several of the later ones too, such as Raoul of Cambrai , Aliscans , The Knights of Narbonne and Aspremont.

It is not until the middle of the twelfth century, as the aristocratic male audience for such tales developed rapidly into a more democratised, and female readership, delighting more in the emotionally tangled battlefields of Romance, that female characters begin to participate much more in the intrigues of the plot, advancing and eventually directing the actions of the hero by their physical, moral and intellectual qualities. In the Song of Roland the maiden Aude dies of a broken heart immediately on hearing of her fianc Rolands death. She brusquely rejects Charlemagnes offer of his own son as a replacement, Which is Prince Louis: what better can I say/ He is my son, the heir to my domains, (ll.37156) thus demonstrating her unswerving loyalty to her betrothed, which is clearly the focus of the little episode for the earliest poet. Her self-sacrificing death complements that of her fianc on the battlefield: She is thus Rolands equal, and her death adds enormously to his posthumous prestige (Hindley & Levy, p.79). However, in the song called Girart of Vienne , written approximately a century later (c.1200), but describing a baronial conflict that is set, historically, twelve months before her betrotheds famous last stand at the battle of Roncevaux, Aude reappears as an independent, even forward young beauty who is quick to exchange witticisms with any man and to flirt openly with her new admirer, an over-ardent Roland, throughout the seven thousand line narrative. The only other heroine in the Song of Roland, the Saracen Queen Bramimond , although bearing the unforgivable stigma (in these early epic poems) of Paganism a narrative attribute which precludes her immediately from being viewed as a figure of admirable i.e.

Christian virtue, is still portrayed in positive terms as a loyal, supportive wife to King Marsile, and as an articulate deputy who is more than capable of representing her husbands cause in his own absence or incapacity to do so. Her very first words to the Christian traitor Ganelon are: I love you much, because my lord and all his men do so(ll.6356). The most successfully drawn and the most admirable example of this helpmeet-heroine figure in Old French poetry is that of Lady Guibourc, the wife of Duke William of Orange (the principal character in a major sub cycle of the Old French epic songs). Guibourc is indeed a vivacious female personage of high relief who, with the possible exception of Aalais in Raoul de Cambrai, surpasses all other heroines in dignity and in accuracy of human portrayal (Herman, p.213). In her we can best see the literary embodiment of the early medieval Christian woman, who was called upon to be her husbands helpmate in every phase of his life, in his active military pursuits as well as in his pleasures. She was strong in her desires, vigorous in her efforts to satisfy them, and quite as crude in her manner of living as her husband.(C.M.

Jones, p.220) A Christian convert, Guibourc demonstrates a resilient, indeed energetic fidelity to her new husband and her new faith throughout every trial and tribulation she encounters in the course of her many appearances in the chansons de . She displays not only physical courage but a moral strength and a ready wit that cheer and inspire her husband even in his most despondent moods. In the Song of William (c.1120) we find her preparing huge meals for her husband and commending his healthy appetite as an innate proof of his momentarily self-doubted vigour. Assembling an army of thirty thousand men on her own initiative, she lies brazenly to them about Williams achievements in order to enlist their support. She offers them inducements of beautiful maidens, while telling William, however, whom she has advised to seek King Louis help in Paris, that if he does not bring back her nephew Guischard alive, she will withhold all her own conjugal favours. (ll. 243751) In the Song of Aliscans (c.1185), a subsequent and much longer remake of the material contained in the second half of the above-quoted tale, the genres earlier martial bias is still heavily evident, and Guibourcs response remains much the same to this same question asked of her by her husband. 243751) In the Song of Aliscans (c.1185), a subsequent and much longer remake of the material contained in the second half of the above-quoted tale, the genres earlier martial bias is still heavily evident, and Guibourcs response remains much the same to this same question asked of her by her husband.